What are microplastics?

Microplastics are plastic particles that are smaller than 5mm in size. To give an idea of scale, the round studs on top of a Lego brick are 4.8 mm across.

Microfibres can be plastics too, for example polyester and acrylic fibres from clothing, but the term also includes non-plastic fibres such as cotton and wool (these 'natural' fibres can also be pollutants, read Thomas' recent paper here).

Where do microplastics come from?

Microplastics are classified into two types based on how they originate. Primary microplastics are those that are manufactured to be less than 5mm, sometimes for use in cosmetics, or as plastic pellets that will be later melted down to make larger plastic products.

Secondary microplastics come from the breakdown of larger plastics. This includes plastic microfibres which are shed from garments when they are washed.

Where can microplastics be found?

“Microplastics have been found globally from the deepest sea to the some of the most remote places such as mountains away from human habitation,” says Dr Laura Foster.

“They’ve been found in the water and sediment of oceans, rivers and lakes, as well as in soils and in the atmosphere. As well as heavily industrialised areas, where you would expect to find all sorts of pollution, microplastic particles have been found in locations as remote as the Arctic and the sea floor,” explains Thomas Stanton.

How do microplastics get into our oceans?

There are many ways that microplastics can enter water systems. As they may be small enough to become airborne, they can be blown into oceans, rivers, and streams, or else washed into them when it rains.

Microplastics can also get into water systems through our waste water, such as that from our homes, industrial wastewaters, and road drainage. Although our water treatment plants in the UK are quite good at sieving out these little plastic particles, some still evade capture.

Additionally, there may be larger bits of plastic that are dumped into water systems, such as that from our rubbish and fishing gear, which breakdown in the water until they become microplastics.

Why should we be worried about microplastics?

“We should be worried because plastic breaks down to smaller and smaller particles instead of biodegrading. The microplastic problem is one that will only get worse as more plastic enters the environment” says Thomas.

Plastics also take a very long time to break down, degrading slowly, often over hundreds if not thousands of years, making them a very long-lasting problem.

What is the impact of microplastics on wildlife?

One major problem is that microplastics can be the same size, and sometimes shape, of food that is eaten by marine wildlife. They are often mistaken for food, which can cause abrasions to the digestive system of animals, reduce the quality of their nutritional intake, and lead to their guts being full of plastic rather than food.

The composition of the plastic itself may also have an impact. The harmful chemicals used in plastic production, such as dyes and plasticisers, can leach out as it breaks down, into animal bodies and into the environment.

Harmful chemicals that are found in the environment can also latch onto the surfaces of microplastics. These include heavy metals, the insecticide DDT (infamous for its toxic effects on wildlife), and the organic pollutant PBC.

Both the chemicals leaching from and those clinging to microplastics can be ingested by animals and then rise through food webs as those chemical-laden animals are eaten by others. This can lead to bioaccumulation of these dangerous compounds in those predators at the top of the food chain.

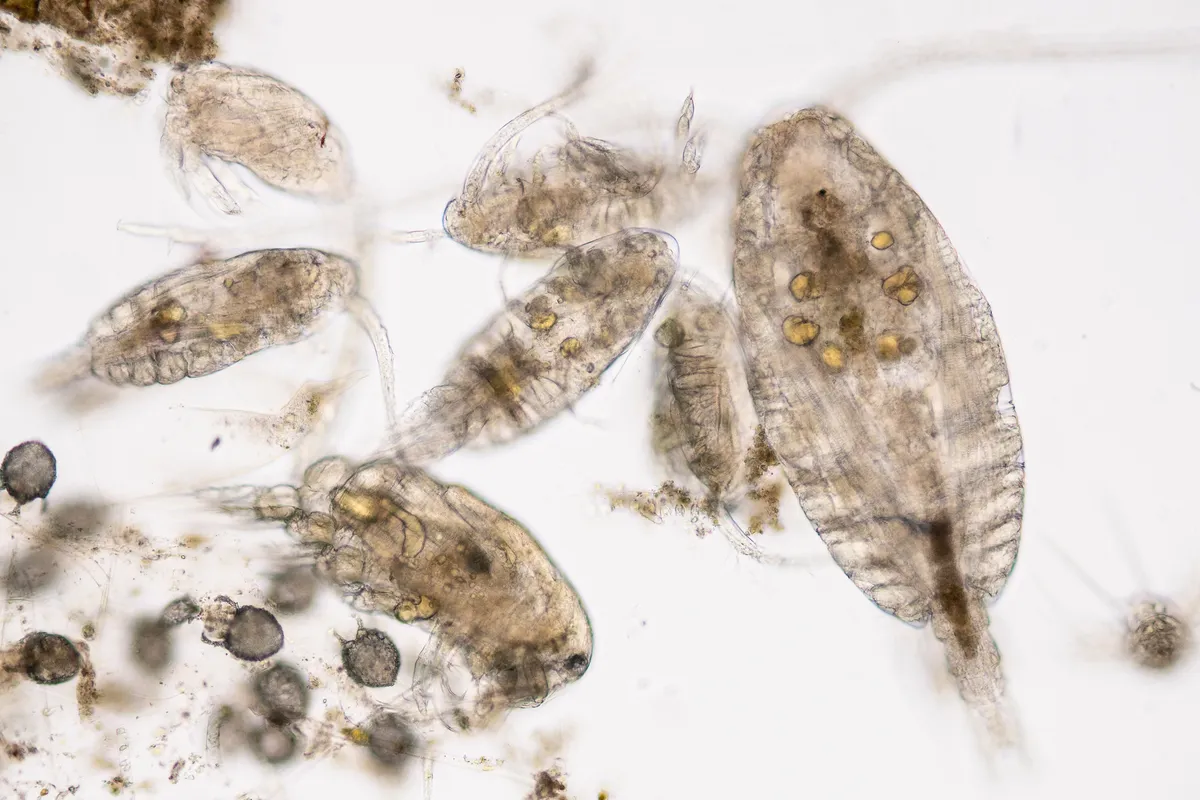

The lasting impacts of microplastic pollution on wildlife are not fully understood. Recent research has however shown that microplastics are readily ingested by zooplankton, tiny animals that are a crucial food source for many marine animals, including fish and whales. Plastic ingestion has been shown to have negative effects on zooplankton feeding behaviour, reproduction, growth, development and life- span. Read more here.

What is the impact of microplastics on human health?

Although we know that humans are exposed to microplastic particles through ingestion, there has not yet been much research on the direct impact on human health. We would need to know much more about the levels of plastic humans are exposed to before we can know what the long-term impacts will be. We should see research on this soon however.

What can ordinary people do to avoid making the problem worse?

People should try to consume less plastic, for example by small changes such as refilling our own water bottles, but should also try to consume less in general, because plastic alternatives can have detrimental environmental impacts too.

“If consumers reduce and reuse what they buy, and recycle what they can, they will reduce the market for many uses of plastic,” says Thomas.

Dr Foster recommends people follow the mitigation solutions proposed by Ocean Clean Wash if they want to reduce the amount of microfibres they release into the environment. This includes simple changes to your laundry habits, such as washing clothes at lower temperatures, filling your washing machine to the max, and using washing liquids instead of powders. You can also buy special washing-machine filters.

What should governments do about microplastics?

“The government needs to shift our economy from a single use economy to one which uses reusables and ensures products can be repaired,” says Dr Foster.

“We also need to have restrictions or bans on inclusion of microplastics in products. The UK has a microbead ban but many more products contain microplastics.”

“Supporting behavioural change by consumers with necessary infrastructure is one step, as is seen in Wales, which is aiming to become the first refill nation, supported by the Welsh government,” says Tom Stanton.

“Governments simply need to take the environment more seriously than they currently do, because plastic pollution is not the only environmental problem that they are not prioritising.”

Main image: Microplastics on the beach. © doble-d/Getty