Coast

Here, where the land meets the sea, the landscape is constantly changing, reshaped by wind and waves, and the ebb and flow of the tide. From rocky shores to muddy estuaries, sand dunes to salt marshes, coastal habitats are incredibly rich in life. You can watch seabirds soaring on the wind, search for porpoises playing in the shallows or explore the fascinating miniature world of a rock pool.

Birds of the sea

All along the coast, the air is filled with the sound of cawing gulls, swooping and diving on the wind. Far below them, wading birds run nimbly along the water's edge. They dance to and fro with the foaming waves, sometimes stopping to probe the sand for shellfish with their long beaks.

Many seabirds live far out in the open ocean, and only come to the coast to breed. Each spring they flock to the cliffs, gathering in huge colonies known as 'seabird cities'. Some, such as shags, perch on craggy outcrops, while others like gannets lay their eggs on narrow rocky shelves. Puffins seek shelter from the elements, choosing to nest in abandoned rabbit burrows on the grassy clifftops. When the last of the young have flown, the cliffs will fall silent – until spring comes again.

In the rock pool

Rock pools only appear when the waves retreat and the tide goes out, revealing miniature underwater worlds. The animals that live here have to cope with crashing waves, changing temperatures and the risk of the rock pool evaporating under the hot sun and disappearing altogether. Conditions are one hour to the next. But despite all this, rock pools rarely the same from teem with life.

Starfish cling to the rocks, crabs lurk in dark corners and small fish dart between fronds of seaweed. At first glance, it may seem like an animal paradise, but look closer still, and you'll see life-and-death dramas being played. Limpets battle against hungry starfish hunting for their next meal, sea anemones fight each other for the best position in the pool, while cuttlefish carefully sneak up on unsuspecting prey.

Tropics

Circling the middle of the Earth are the warm crystal clear waters of the tropics. Near the shore, young fish dart between the tangled roots of mangrove trees, while bright corals provide homes for some of the most bewitching creatures of the Ocean. In shallow seas, waving seagrasses form underwater meadows, grazed by a whole host of species, from fish to turtles to slow-moving manatees.

Home sweet home

Small, stripy clownfish live together among the waving tentacles of another reef creature – the sea anemone.

The anemone's tentacles are deadly to many fish, but clownfish have protection against its sting. A young clownfish will gently brush parts of its body against the anemone's tentacles. Over time, this enables the fish to build up a layer of mucus, which protects it from the anemone's stings.

The sea anemone provides the clownfish with food scraps, and its tentacles give safety from predators. In return the clownfish cleans the anemone, ridding it of parasites, and chases away butterfly fish that come to feed on the anemone.

Amazing journeys

Swimming through the warm water comes a crowd of baby sea turtles. They have just survived a perilous journey down the beach where they hatched, past hungry crabs and gulls, into the welcoming waves of the sea.

Only two months before, the mother turtles arrived at the beach to lay their eggs. Each female dug a hole in the sand, filled it with eggs, then covered the hole before returning to the sea. Now the hatchlings have made it to the ocean, they will drift for years on the currents, eating plankton, prawns and small jellyfish. As they grow older they will swim along the coast feeding on sea grasses. One day, the females will return to the beach where they were born, and at last lay eggs of their own.

Open ocean

Far out to sea, beyond the coast, lies the vast expanse of the open ocean. It covers more than 60 per cent of the Earth's surface and its predators must travel far and fast in their search for food - there is much less to go around than in the shallow seas. There are creatures here that spend their entire lives surrounded by water on all sides, some never seeing land or even sunlight.

Fast and free

From dolphins to marlins to tuna, some of the fastest swimmers in the ocean inhabit its open waters. They often live in large groups, thousands strong, for protection against predators.

Schools of tuna can reach speeds of up to 48 kilometres per hour, their silver scales flashing as they cover vast distances in search of food. To escape the tuna, flying fish have evolved torpedo-shaped bodies, enabling them to swim fast enough to break the surface of the water. Dolphins, too, reach great speeds as they hunt. They can leap from the water, twisting and turning before plunging beneath the waves.

Mysterious giants

The largest fish in the sea, whale sharks are as long as a bus.

They feed by sucking in water through their giant gaping mouths and then filtering out tiny plants and animals.

Whale sharks swim slowly, but will travel huge distances in search of food, and are capable of diving to incredible depths. Despite their vast size, little is known about their lives. However, each whale shark has a unique pattern of spots and pale stripes, which helps researchers to identify individuals.

Polar waters

At the very top and bottom of the world lie the north and south poles. Here it is cold all year round and much of the water is frozen in sheets of thick white ice. Despite freezing temperatures, there is a huqe abundance of life. The waters are thick with plankton and krill, which attract vast schools of fish, miqratinq whales, flocks of

seabirds and huge colonies of seals.

Waddle and wait

It is April in Antarctica: the sea ice has thickened and thousands of Emperor penguins have come inland to breed. Each penguin has a thick layer of fat and closely-packed feathers, but in the bitter cold they must huddle together for warmth.

The females each lay a single egg, then return to the sea to hunt, leaving the males to care for the eggs. For the females it is a long journey of over 100 kilometres. But for the males, it is a tough, two-month wait through the winter.

On the female's return, both parents take turns to look after their chick. They waddle and toboggan to the ocean and back to meet its demands for food. By December, the chick is finally old enough to swim and fish. At last, it can leave the frozen wastes of sea ice and take to the water with its parents.

Unicorns of the sea

Known as unicorns of the sea' for their sinqle white tusks, narwhals only live in Arctic waters.

These mysterious creatures are cousins of dolphins and porpoises. They live in small groups, gliding under sea ice before bobbing up for air. The narwhal's tusk was once thought to have magical powers and was worth more than gold. We now know it to be a long, spiralling tooth, usually found only in males. It grows up to 2 metres long and has thousands of nerve endings. A narwhal will use its tusk to impress rivals, stun fish and to sense its surroundings in the murky polar waters.

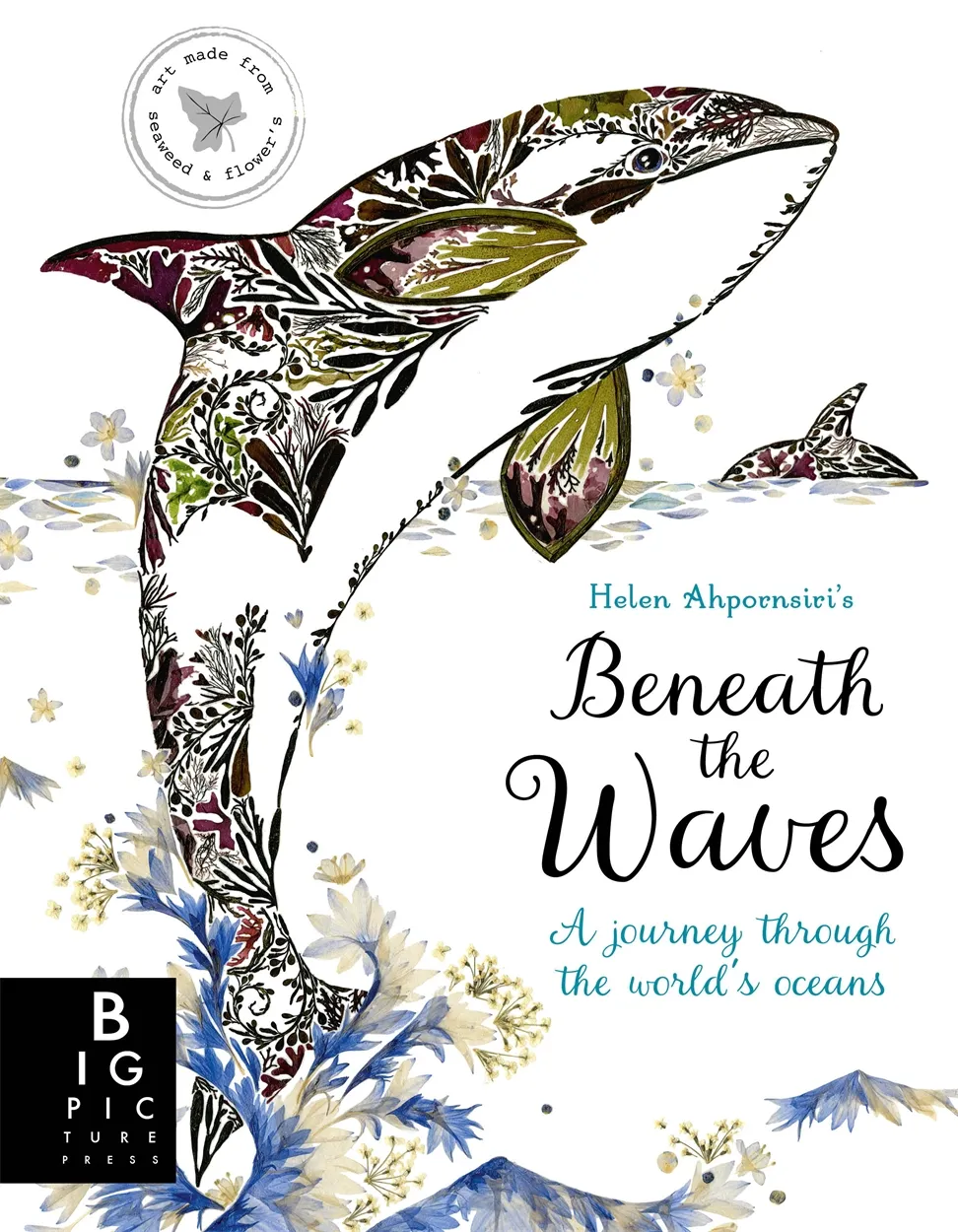

This is an abbreviated edited extract from Beneath the Waves by Helen Ahpornsiri, published by Big Picture Press.