A complex, eerie winnowing fills your ears. An intense, multi-harmonic pulse that seems so completely out of place on Earth, it might have you scanning the sky for an impending alien invasion. Yet this acoustic ambience places you precisely in both habitat and time – the air over Britain’s marshy areas will be resonating with the strange music from spring through to summer.

The fact that the source is so difficult to locate only fuels its mystery. But look carefully skywards and you might be lucky enough to spot the distinctive, long-billed profile of one of our most secretive birds, the ‘common’ snipe. It is doing what is often called drumming.

What is drumming and how loud is it?

It’s a big sound that carries up to 0.8km – the all-pervading noise is out of proportion to the wader’s diminutive size, which can make it difficult to pinpoint. The emanation, however, is not a ‘song’ in the usual sense of the word. No, the fabulously odd drumming is a sound reserved for the skies – it can only be produced in the air by mechanical means. Sounds made in this way are known as sonations to distinguish them from the more usual types of bird vocalisations.

In common with many other birds, the snipe does also have a true voice, making a varied repertoire of croaks and grunts and a distinctive ‘chip… per… chip… per… chip’ song. These utterances, as in other species, are produced by the syrinx: a sophisticated collection of membranes under muscular control in the bronchi.

What do snipe look like when they drum?

Should you manage to locate a snipe while it is drumming, you’ll see its arrow-like body describe an ascending arc before it rapidly plummets at about 40–45 degrees; it is during this powered descent that the sound is produced. The delay of the sound reaching your ears can make syncing the physical actions and sound a little difficult. But if you have a ‘sniper’s’ wits about you, you might be able to get your binoculars on the bird, and in a really good view you’ll notice the strange form of its tail.

As it descends, the male sticks out its two outer tail feathers at near 90° to its body, and when it reaches speeds of 50–85kph, they start to vibrate. The faster the bird dives, the higher the pitch of the sound created.

How do snipe drum?

As it descends, the male sticks out its two outer tail feathers at near 90° to its body, and when it reaches speeds of 50–85kph, they start to vibrate. The faster the bird dives, the higher the pitch of the sound created.

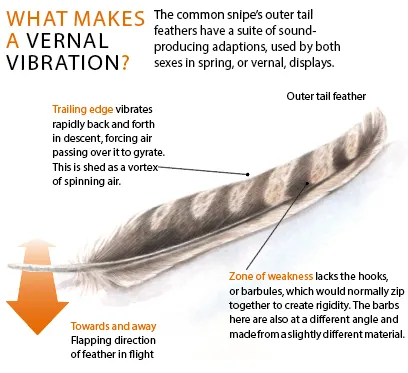

Recent research has shown that aeroelastic flutter produces the noise, a phenomena that is a self-feeding vibration, a function of interaction

between the wind speed and the structure of the feathers.

The pair of specialised sound-making feathers are stiffened, except for a zone of weakness along their length. This sets up a zone of flexion, which causes the trailing edge of each feather to flap backwards and forwards violently as air passes over it. Think of it like a flag flapping in the wind but at a higher frequency and you have the mechanism behind one of the most unique territorial display flights of any bird.

Main image © Peter David Scott/ The Art Agency