This group of aquatic, flightless birds mostly live in the southern hemisphere with only one species found right on the equator. Find out how to identify each species of penguin, from the deepest diver (emperor penguin) to the fastest swimmer (gentoo penguin). In our expert guide from polar science and operations centre, the British Antarctic Survey, discover how scientists count penguins, how species in cold climates stop their feet from freezing, what penguins eat, whether they have any predators and the best places to see these birds in their natural habitat.

How many species of penguin are there?

There are 18 species of penguin which are found in a variety of countries, all the way from Antarctica to the equator. Fossil records show that there were at least 25 species of penguin in the past, several of which have gone extinct.

In 2020, scientists published research that indicated that the two subspecies of Gentoo penguin should actually be classified as four separate species.

- King penguin, Aptenodytes patagonicus

- Emperor penguin, Aptenodytes forsteri

- Adélie penguin, Pygoscelis adeliae

- Chinstrap penguin, Pygoscelis antarctica

- Gentoo penguin, Pygoscelis papua

- Little penguin, Eudyptula minor

- Magellanic penguin, Spheniscus magellanicus

- Humboldt penguin, Spheniscus humboldti

- Galápagos penguin, Spheniscus mendiculus

- African penguin, Spheniscus demersus

- Yellow-eyed penguin, Megadyptes antipodes

- Fiordland penguin, Eudyptes pachyrynchus

- Snares penguin, Eudyptes robustus

- Erect-crested penguin, Eudyptes sclateri

- Southern rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes chrysocome

- Northern rockhopper penguin, Eudyptes moseleyi

- Royal penguin, Eudyptes schlegeli

- Macaroni penguin, Eudyptes chrysolophus

Where do penguins live?

Everyone imagines penguins on the ice in Antarctica or taking a break on a passing iceberg, but penguins are also found in South Africa, Chile, Peru, Galápagos Islands, New Zealand, Australia and a number of sub-Antarctic islands.

Penguins are very nearly exclusive to the southern hemisphere, but Galapagos penguins live right on the equator and so there are a few penguins living in the northern hemisphere.

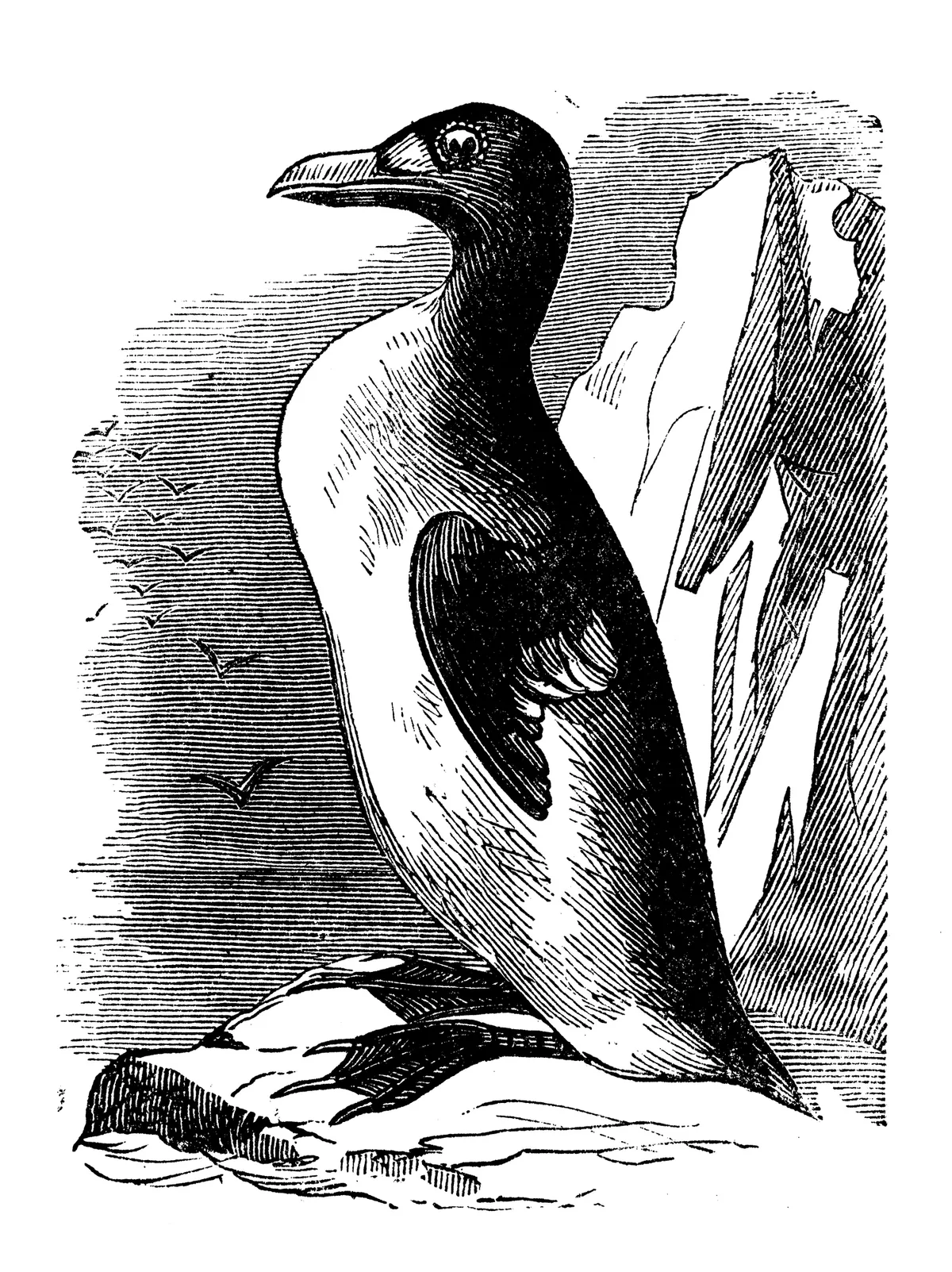

How was the penguin named?

The name penguin was originally given to an unrelated bird species – the now-extinct great auk, which was a large, flightless, black and white bird. When explorers first encountered wild penguins, they used the same name for the new creatures they were seeing.

Adélie penguins are named after the wife of Jules Dumont d’Urville, the French Antarctic explorer (he also named Terre Adelie/Adelie Land after her).

Are penguins birds and can they fly?

Yes, penguins are birds, although they are flightless birds. Lots of people think penguins are mammals rather than birds because they can't fly, and we see them swimming underwater or waddling on land instead. But there are other birds that can't fly (like emus, ostriches and cassowaries), and penguins fulfil all the biological requirements to be classified as birds - they have feathers, they lay eggs and they're warm-blooded. They're just seabirds that are very well adapted to their unusual lives, which is why they're so different from other birds.

What do penguins eat?

Penguins eat a variety of seafood such as fish, squid and crustaceans. The smaller penguins usually feed on krill.

Climate change is likely to affect the numbers of krill, and thus affect the penguins as well. Since the 1970s, krill density in some areas has decreased by 80 per cent.

Do penguins have feathers?

Penguins have feathers just like all other birds. Penguin feathers are shorter and stiffer than most bird feathers, which makes penguins more streamlined in the water and traps more air to provide better insulation.

Do penguins have knees?

Penguins do have knees, you just can't see them hidden away under all those fluffy feathers. They don't even have particularly short legs, so why do penguins waddle?

Scientists think it's because penguin legs have evolved to help them swim more efficiently, which has resulted in them being set further back on the body than you might expect. That makes walking more difficult, and the classic penguin waddle is the result.

How many king penguins are there?

The total population of king penguins is about 2.23 million breeding pairs. That’s a lot of penguins! Their population is increasing too, and due to their extremely large range and numbers the IUCN lists them as of Least Concern in terms of extinction risk.

King penguins form vast breeding colonies, for example a colony on South Georgia Island holds over 100,000 breeding pairs.

How do emperor penguins keep warm during the Antarctic winters?

The emperor penguin is the only species that spends the harsh Antarctic winter on land – the males protect their eggs from the cold ice by keeping them on their feet. The females are off at sea during much of this time.

Emperor penguins are able to cope with this cold as they have the highest density of feathers of any bird species – 100 feathers per square inch!

Do penguins get frozen feet and how do they conserve heat?

Penguins loose a lot of heat through their feet and flippers, so they have a highly developed vascular system to minimise this heat loss. When the ambient temperature falls below 0˚C, a penguin increases the circulation of warm blood to its feet. But, while this prevents the feet from freezing, it also increases the heat loss. To combat this, penguin vascular systems have a counter-current heat exchange system for their extremities.

This works by passing warm arterial blood from the body through fine arteries in close contact with veins returning from the feet and flippers. The warm arterial blood is cooled before it reaches the extremities, while the returning blood is warmed before it can chill the body.

These adaptations work so well that they can actually cause penguins to overheat in areas of higher temperatures. So species in warmer places like South Africa have large flippers and bare areas on their faces.

How do scientists count penguins?

Scientists can undertake population counts of penguins in inaccessible areas by using high-resolution satellite imagery. They are able to differentiate between birds, ice, shadow and guano (penguin poo).

How tall is the emperor penguin?

Adult emperor penguins are 1.2m tall, which makes them the tallest penguin species. The smallest species is the blue penguin (also known as the little penguin or fairy penguin) at just over 0.3m tall - 4x shorter than emperor penguins.

One extinct penguin species, known by the scientific name of Anthopornis nordenskjoldi, was even larger than the emperor penguin, standing an impressive 1.7m tall!

How have penguins adapted to swimming?

Many bird species are adapted to flying by having hollow bones, whereas penguins have dense bones, which makes diving easier.

How deep can penguins dive?

Penguins can dive to depths of over 250m, although most dives will be within the top 10m of water. The deepest dive ever recorded is by a female emperor penguin that dived to 535m below the surface!

Which is the fastest penguin species?

The fastest species of penguin is the gentoo penguin, which can swim at up to 22mph.

Are there any gay penguins?

Gay penguins were first observed over a century ago by the British explorer George Murray Levick, who documented extensive homosexual sex between Adelie penguins. He also recorded other unexpected sexual behaviour that was deemed too shocking to become public knowledge at the time. To avoid anybody but educated gentlemen becoming aware of his discoveries, he wrote the more controversial parts in Greek.

Since then, gay penguins have been documented across several species, with widely publicised accounts of homosexual penguin couples in zoos successfully raising adopted chicks.

Do penguins have any predators?

Leopard seals, sea lions and orcas (killer whales) will all eat penguins, although leopard seals are usually the biggest threat in Antarctica.

Penguin chicks and eggs aren't safe either, with skuas hanging around penguin colonies to pick off any young left unattended.

How are penguins adapted to saltwater?

Due to eating so much seafood, penguins need to be able to cope with the high amount of salt in the saltwater. They have a gland located just above their eye called the supraorbital gland, which filters the salt from their bloodstream. This is then excreted through the bill, or by sneezing!

Penguins undergo a process called catastrophic moulting, when they replace all of their feathers in the space of a few weeks. During this time, they cannot enter the water so they need to have accumulated enough fat to fast through this period. Most birds replace their feathers gradually over the course of the year, while penguins have to go through this process all at once.

What species are penguins most closely related to?

A penguin's closest relatives are petrels, albatrosses and divers.

British Antarctic Survey (BAS), an institute of the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), delivers and enables research in the Polar Regions with staff based in Cambridge, Antarctica and the Arctic, to advance our understanding of Earth as a sustainable planet. Find out more about their work: www.bas.ac.uk