The golden eagle is a magnificent raptor and the second largest bird of prey in the UK, after the reintroduced white-tailed eagle. Even when spotted soaring at a distance, it is distinctive enough to distinguish it from the white-tailed eagle and other birds of prey such as the buzzard and the red kite.

The golden eagle is listed as a Schedule 1 species, and has suffered from persecution, both in the UK and abroad, and is still occasionally killed illegally. Due to this historic persecution, the species became extinct in England and Wales by 1850, and in Ireland by 1912. A pair returned to the Lake District in England in the late 1960s.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the species suffered from infertility and eggshell thinning due to the accumulation of pesticides in their bodies.

Learn more about this fascinating bird in our expert guide by wildlife and travel writer Mike Unwin:

What is the scientific name of the golden eagle?

The scientific name of the golden eagle is Aquila chrysaetos. The genus name ‘Aquila’ is Latin for eagle, whilst the specific name ‘chrysaetos’ is derived from Ancient Greek where ‘khrusos’ means gold and ‘aetos’ means eagle.

There are eleven extant (living) species in the Aquila genus, known as ‘true’ or ‘booted’ eagles, the golden eagle is the type species (the species that the genus is permanently associated with in taxonomy):

- Bonelli's eagle (A. fasciata)

- Cassin's hawk-eagle (A. africana)

- African hawk-eagle (A. spilogaster)

- Golden eagle (A. chrysaetos)

- Eastern imperial eagle (A. heliaca)

- Spanish imperial eagle (A. adalberti)

- Steppe eagle (A. nipalensis)

- Tawny eagle (A. rapax)

- Verreaux's eagle (A. verreauxii)

- Gurney's eagle (A. gurneyi)

- Wedge-tailed eagle (A. audax)

How to identify golden eagles

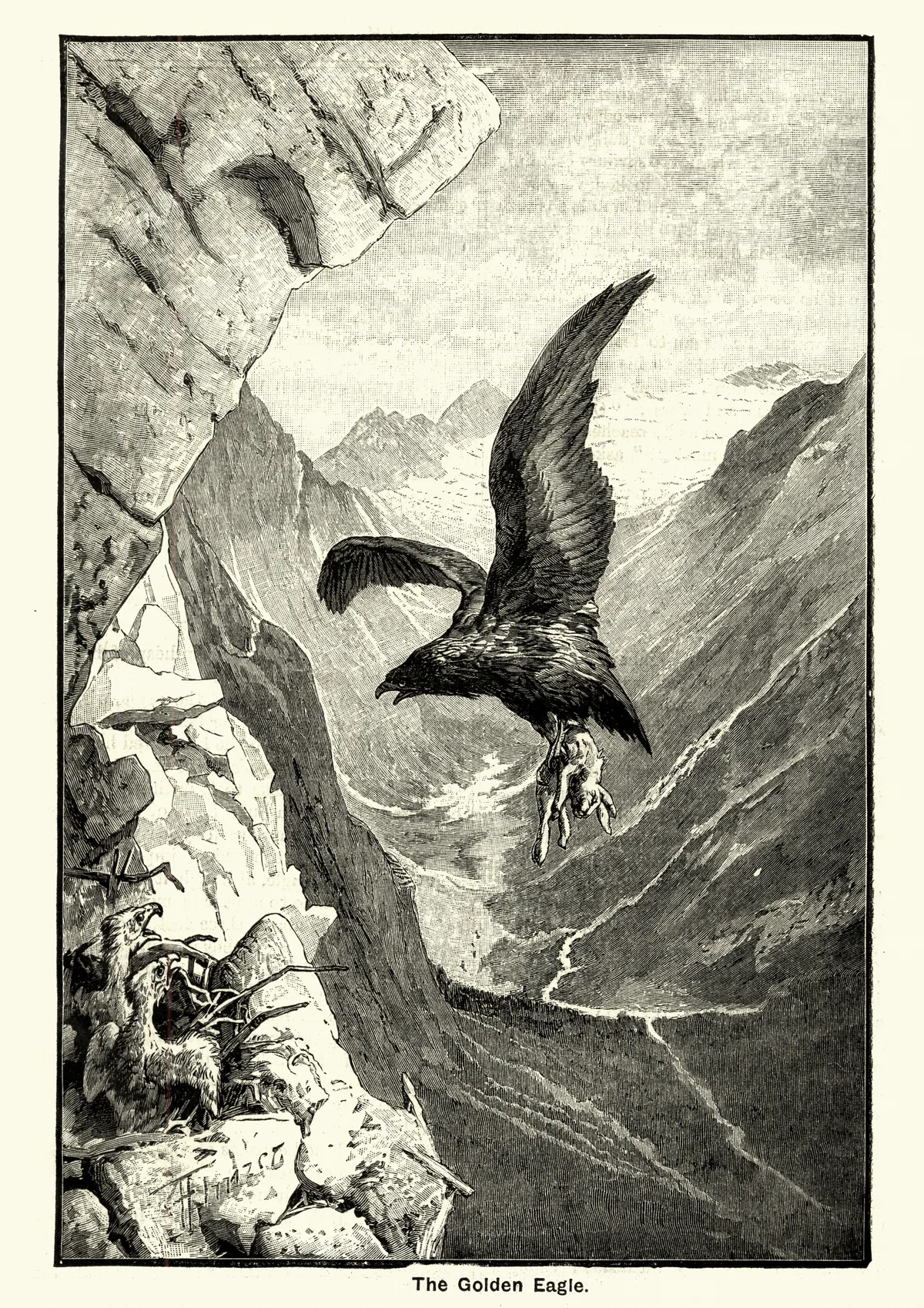

Adult golden eagles are essentially dark brown. They have a sandy nape that flashes gold in sunlight – hence the name – and areas of paler grey on the wings and tail.

Immatures have striking patches of white on the primary wing feathers and tail, which gradually shrink as a bird matures and have usually disappeared by its fifth year. Other key features of this spe-cies are the bright yellow legs and yellow cere – the skin at the base of the bill.

In the field, it is by shape rather than colour that you are most likely to identify a golden eagle. Its long neck and massive bill are more prominent than those of smaller brown raptors and in flight protrude appreciably further – as does the tail.

Its head is less prominent than that of a white-tailed eagle but its tail is longer. The massive wings are more graceful in their contours than the white-tailed eagle’s (below). When soaring they are spread in a shallow ‘V’ – or dihedral – unlike those of any other raptor of the same size, with the primary tips splayed like fingers.

How big are golden eagles?

The golden eagle is the biggest species in the Aquila genus of eagles, otherwise known as the ‘booted’ or ‘true’ eagles.

Females are some 20–30% bigger than males, a phenomenon called ‘reversed size dimorphism’ (‘reversed’ because in most birds and mammals where one sex is larger than the other, it is generally the male). In the UK, the average male weighs 3.7kg and has a wingspan of 2.0m, and the female 5.2kg and 2.2m.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Golden Eagle Flying In Slow Motion | BBC Earth

Where are golden eagles found?

The golden eagle enjoys a wide distribution right across the northern hemisphere, although nowhere is it numerous.

In Britain the golden eagle is confined almost entirely to Scotland, where it inhabits the wild mountains and glens of the Highlands and also some of the Hebrides. A relict, isolated population in England’s Lake District has for some years now consisted of just a single lonely male.

A recent reintroduction programme aims to re-establish Golden Eagles in Ireland, where they died out in 1912.

What do golden eagles eat?

Typical prey for the golden eagle comprises small to medium-sized, ground-dwelling animals of around 1–2kg, such as rabbits, mountain hares, red grouse and ptarmigan.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Eagle vs Hare | Predators | BBC Earth

Scientists have recorded more than 400 species in its diet worldwide. The upper limit in prey size is more a reflection of carrying than killing power: a golden eagle struggles to lift anything heavier than itself, but is perfectly able to kill an adult deer.

This capacity for killing large mammals has led the golden eagle into serious trouble. Farmers around the world have long blamed the bird for taking their lambs and other livestock. In reality, such attacks are a very small part of the golden eagle’s predatory behaviour in most of its range.

Eagles caught feeding on sheep carcasses are invariably taking advantages of dead animals they have come across; this raptor, whilst being a deadly hunter, is also a consummate scavenger.

When is Golden Eagle Week?

The Scottish town of Moffat has been declared Scotland – indeed the UK’s – first ‘Eagle Town’, and its inaugural ‘Golden Eagle Week’ took place in September 2021.

The festival was organised by the South of Scotland Golden Eagle Project, which recently successfully translocated eight eaglets from the Highlands to the Southern Uplands of Scotland.

The project aims to bolster numbers living in the wild and ultimately restore this magnificent predator to the areas it used to inhabit.

By rehoming the birds, the project has brought the number of golden eagles living in the area to 12 – almost doubling its local eagle population.

This is an edited extract from RSPB Spotlight Eagles by Mike Unwin, published by Bloomsbury.

- Buy now from Amazon, Bookshop, Hive, Waterstones

Mike Unwin is the author of more than 35 books for adults and children, including the RSPB Bird Encyclopedia, RSPB Spotlight Swifts and Swallows and Migration: Incredible Animal Journeys. A specialist in natural history and travel, he writes regularly for numerous publications. Mike was voted UK Travel Writer of the Year 2013 by the British Guild of Travel Writers.

Main image: A male golden eagle on heather moorland. © Chris Upson/Getty