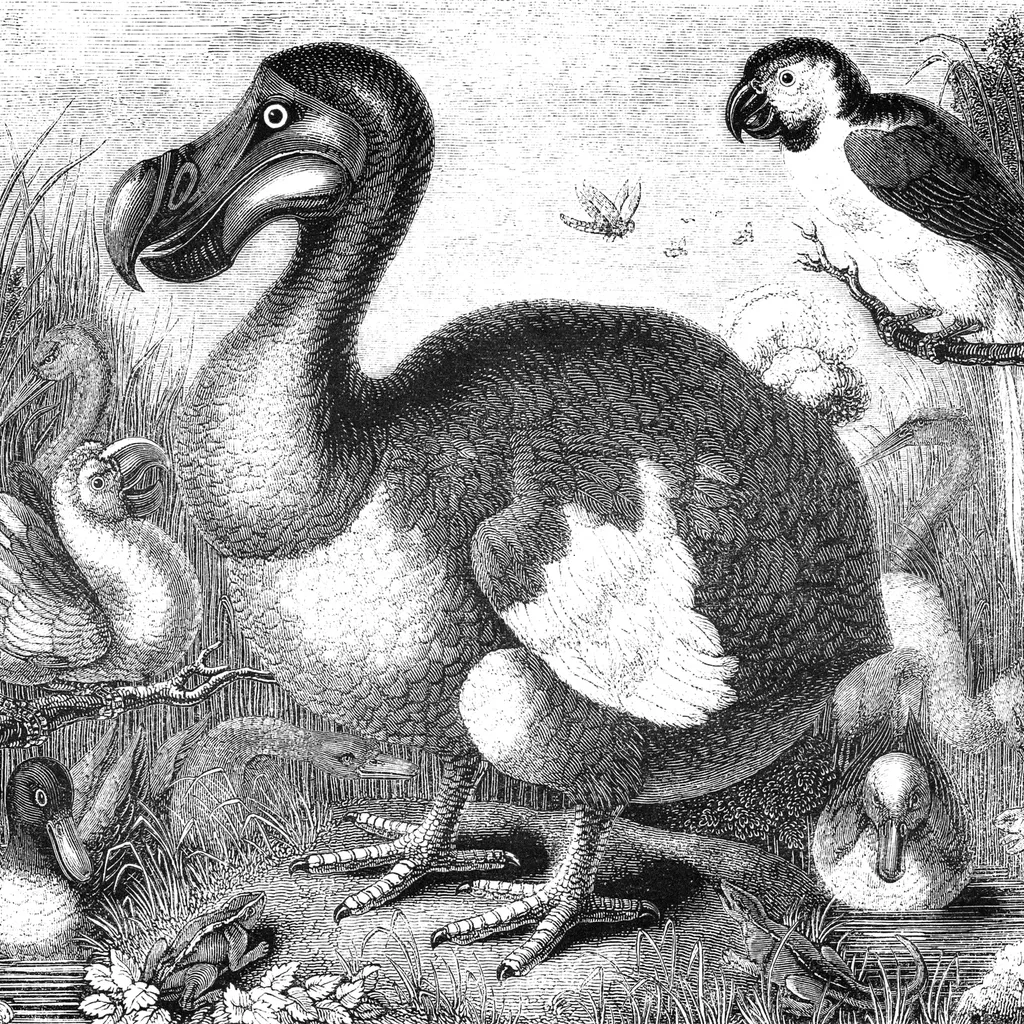

The dodo, a large flightless bird endemic to the small Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, has been extinct since the 17th century. But this poster species for extinction is now one step closer to a return to its island home.

Ambitious plans to bring back the dodo were announced in January 2023, following the news that scientists at the Genomics Institute at the University of California, Santa Cruz had sequenced the dodo’s genome from a DNA sample taken from a museum specimen.

Now Colossal Biosciences, the US-based biotechnology and genetic engineering company attempting to resurrect the dodo, has partnered with the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF) to restore habitat that will be necessary for its eventual reintroduction.

“The habitat of the dodo has been greatly modified through well over four centuries of human colonisation of Mauritius,” Vikash Tatayah, Conservation Director of the MWF, told BBC Wildlife.

Not only has agriculture, forestry and human infrastructure led to the loss of habitat, but the predators that contributed to the extinction of the dodo in the first place – cats, rats and pigs among them – are still all present on Mauritius. These predators, and more recent arrivals, would need to be excluded or controlled in areas where the dodo would be rewilded. Another option would be identifying areas that are already free from predators, such as several of the small islands off Mauritius.

Other factors to consider as part of a feasibility study that will be funded by Colossal are the presence of endemic plants. With many species notoriously slow growing, work must begin as soon as possible.

Any work on the ground done with the dodo in mind would also benefit conservation on Mauritius more widely, said Tatayah, citing species such as the pink pigeon and Mauritius olive white-eye: “Habitat restoration, predator control, supplementary feeding, disease control, education, these are all skills transferable across projects.”

- Prehistoric aurochs are back from extinction and spreading across Europe. And they could be heading to the UK

- Mythical-looking scimitar-horned oryx reclassified from Extinct in the Wild to Endangered

It is likely to be many years before a bird resembling the dodo could be returned to Mauritius, however, given the complexity of the science involved.

Since sequencing the dodo’s genome, paleogeneticists at Colossal have mapped the genomes of two other related species with a view to one day creating hybridized animals through reproduction. By mapping the genomes of the solitaire, an extinct flightless bird which lived on nearby Rodrigues Island, and the Nicobar pigeon, the closest living relative to the dodo, scientists hope to be able to edit cells that act as precursors for ovaries and testes to make them express the physical traits of the dodo. These cells, called primordial germ cells, would then be inserted into the embryos of a sterile chicken and rooster, whose offspring would, in theory, resemble the dodo.

Why did the dodo go extinct?

What exactly caused the dodo to go extinct? And could it ever be brought back to life?

When Europeans began to settle on Mauritius in the 16th century, the sailors and the invasive species they brought with them sealed the dodo’s fate. Before they arrived, the dodo lived a charmed life on an island where food was plentiful and predators absent. But the sailors and their animals hunted it for food, raided its nests for eggs, and destroyed its habitat.

Its brutal eradication from its only home has seen the dodo become almost a byword for extinction. But with the advance of genetic engineering technologies, would it really be possible one day to bring the dodo back from extinction?

Can the dodo really be brought back from extinction?

In 2022, Beth Shapiro from the Genomics Institute at the University of California, Santa Cruz, announced the sequencing of the dodo’s genome. It was sequenced from a DNA sample taken from a specimen held at Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum. So is this icon of extinction poised to return from the dead?

“There are a tonne of existing technical challenges that would need to be solved in order to bring a dodo back to life,” she told BBC Wildlife in 2022.

“First, one needs to be able to figure out what genetic differences in the dodo genome make the dodo look and act like a dodo. One would also need to figure out how to make those genetic changes, which are surely more than a few, in the types of cells that are destined to become a living animal. In birds, this would mean using gene-editing tools on what are known as ‘primordial germ cells’, which are the cells that will eventually become sperm or eggs. After that, one would have to solve all of the normal problems associated with captive breeding and husbandry of a species that no longer exists.”

Would the dodo survive today?

Even if it were possible to recreate the dodo, that wouldn’t solve the problems that caused the bird to go extinct in the first place, as Beth explained: “We believe that dodos became extinct because introduced species including rats, cats and pigs consumed their eggs. Because dodos didn’t fly, they nested on the ground.

“This made their nests easy access for potential predators and consumers of eggs. It would not make sense to bring dodos back to Mauritius unless this challenge could be solved.”

It’s a hot topic, with strong views on all sides. “De-extinction is not a solution to the extinction crisis of the present day,” Beth said.

Rather, such technologies offer the potential to edit the genomes of current threatened species in order to help them adapt to changes in habitat and climate.

“Our new biotechnologies may someday make it possible to transfer some extinct traits to living species, but the end products of any project like this will be something different than the species that once existed. Every organism is more than just the As, Ts, Cs, and Gs that make up their DNA code. We are combined products of our DNA and the environment in which we live.”

So does this rule out the idea of bringing the dodo back from the dead?

“We may get close someday. We may figure out how to make enough changes in a genome that we can engineer something that is physically similar to a dodo. And maybe that bird, returned to the Mauritian ecosystem, will fill the ecological niche that the dodo once filled and provide some improved stability to the Mauritian ecosystem. And that would be great.”

So why sequence the DNA?

Beth believes there’s a more pressing concern that this kind of work may be able to help with. “These technologies will also help us to solve more proximate challenges. We will learn to edit the genomes of species that are still alive but in danger of becoming extinct, to help them to adapt to their rapidly changing habitats.

“The same technologies that might eventually be used to re-create something that approximates an extinct species will be useful to help preserve species that are still alive. To protect those species from going the way of the dodo.”