Secret rituals and specimen jars in the fridge can only mean one thing – it's moth time...

I found an old lady in my lampshade last night

Of course she was dead – she’d been lured by the light

But her lace was unsinged, and her smock undefiled

So I took her downstairs, and I called to my child…

The old lady was, of course, a moth, and the child was my youngest daughter, Rosie.

“Why do you think it is called an old lady?” I asked her.

“’Cause it looks like a lacy frock thingy,” she replied.

“A crinoline?”

“Whatever.”

After a few seconds, Rosie and I spoke in unison: “And this affects me how?”

She first uttered this immortal expression of teenage indifference aged 13, when I showed her a fox. Rosie is now 24 and, while she is not exactly a committed naturalist, she is appreciative of most of the wild things I draw her attention to.

Meanwhile, “And this affects me how?” has become a family catch phrase. As, indeed, has “Dad! Oh my God!”, indicating that someone has opened the fridge door and discovered the specimen jars lurking in the egg rack.

They may look like moth coffins but I assure you that the occupants are only sleeping – or, rather, in torpor. When I release them, their wings will shiver and quiver until they fly off, hopefully avoiding the robin who has learned to recognise the appearance of my moth tray as the promise of a meal.

Simple pleasures

I am an inveterate garden moth-er. I have a very basic kit: a wooden box, a bright light, clear plastic sheets and – to provide both shade and warmth for the moths – a layer of egg boxes.

This year I set up the trap for the first time on 25 March. The day had been unseasonably warm, but the night was chilly – so I wasn’t too hopeful.

Nevertheless, come morning I had five moths in my trap – two common Quakers, two Hebrew characters and a brindled beauty.

Add in the old lady, and you may deduce one of the reasons why I love moths – their names!

Some are simply descriptive: scalloped hook-tip, pinion-streaked snout; others more playful: maiden’s blush, true lover’s knot; and a few fearsome: death’s head hawkmoth.

All of them are testimony to the diligence and imagination of the Victorian naturalists who catalogued and named them.

Moth Club collective

Get into moths and you become a member of a club: literally – moth groups abound – or in a less orthodox way.

I first realised this when I filmed an item for Bill Oddie Goes Wild. My producer, Alex, had clearly grasped the notion: we met at dusk and filmed a circle while chanting, “The first rule of Moth Club is – you don’t talk about Moth Club.”

Each member intoned their name and origin – “Jack from Tewksbury”, “Timothy from Chipping Norton” – then stood by their traps, which were all home-made and collectively looked like an outdoor exhibition of scrap sculptures.

There was a ritual, synchronised turning-on of mercury-vapour lamps, followed by two hours of me talking to the camera while the club members quaffed red wine, an activity that continued well into the small hours as we all pored over our ID guides.

Another rule of Moth Club is that no moth goes unnamed.

Alex’s closing shot, filmed through the cottage window, showed us crouched over a desk surrounded by our wineglasses and empty bottles, all romantically lit by an oil lamp. You could just hear the lady of the house offering a choice of coffee or cocoa, while inebriated voices struggled with tongue twisters such as “three-humped prominent”. At least one person was asleep.

It was one of those experiences that reminded me that there is more to watching wildlife than the wildlife – company, humour and shared enjoyment.

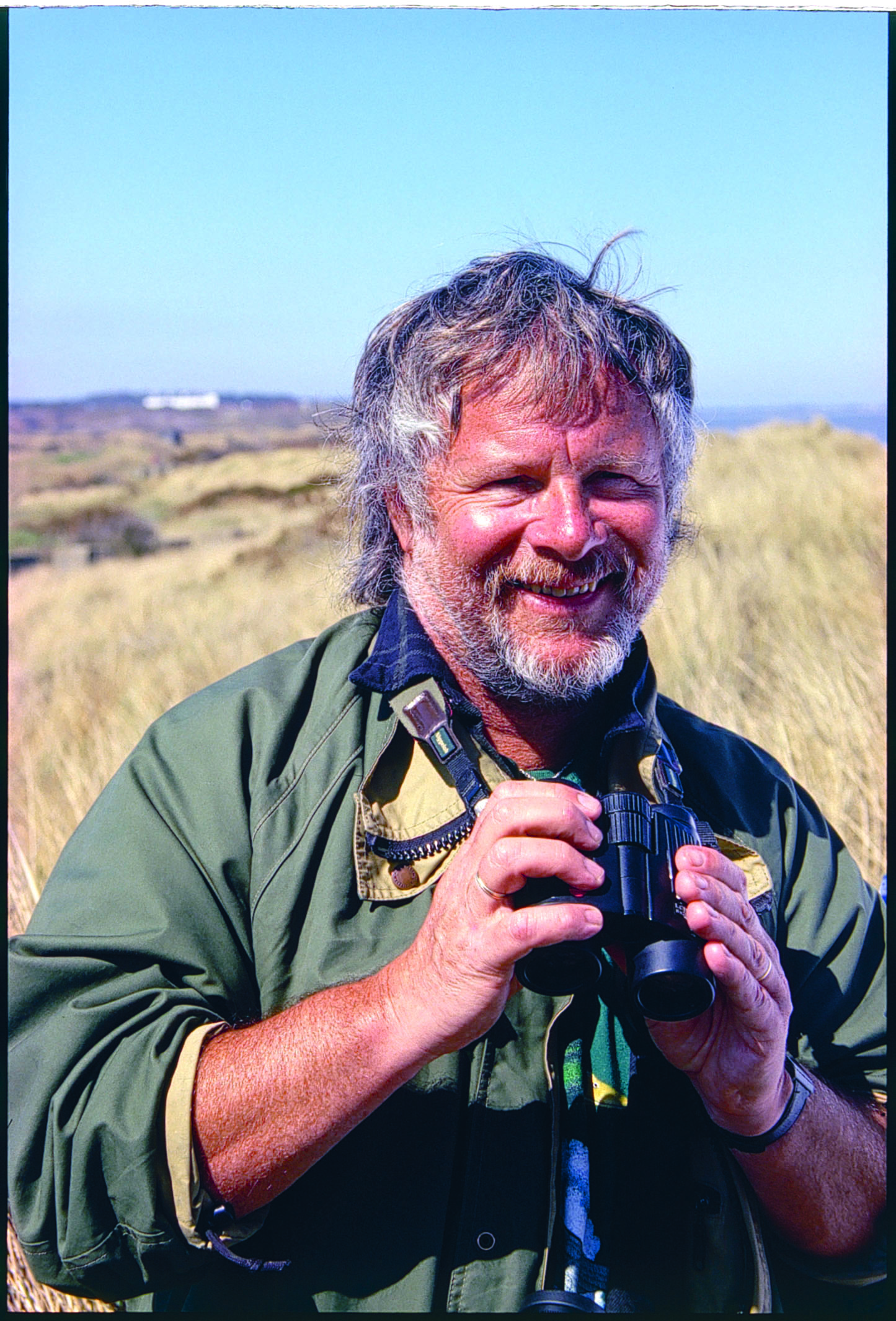

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column is a bit of both.