The only thing that Bill required to become a pitch-perfect wren was a little more speed.

Everyone knows that the playback speed of recorded sound makes a difference to its pitch. Fast equals high pitch, while slow equals low.

Mind you, this principle can’t be easily demonstrated on a CD or MP3 player. It was much simpler with vinyl.

Play a 45rpm disc at 78rpm and it sounded like Pinky or Perky. Play it at 33rpm and you’d hear the voice of God. But is this just a bit of fun, or could there be something more to it?

Deadly dawn chorus

A couple of years ago I visited the studios of Andy Sheppard, a world-class jazz saxophonist renowned for incorporating natural sounds – in particular birdsong – into his music. The inspiration for this came from irritation.

He had been playing at a club in Germany, and such is a jazz musician’s schedule that he only got to bed as the sun was rising and the birds were beginning to sing.

The dawn chorus line-up included a blackbird that was so loud he kept Andy awake. The song was so lovely, however, that instead of cursing he recorded it, and this process was so relaxing that he finally nodded off.

When he woke up, many hours later, Andy reached out of bed and clicked on the tape recorder. What he heard scared him to death. Instead of the mellifluous melody of a blackbird, his earphones were filled with a low rumble that, he told me, was “like dinosaurs in the movies”.

He soon realised that he’d accidentally played back the blackbird’s song at a much slower speed, transforming it into the roar of a T. rex. He increased the speed a little, and found that the dinosaur turned into a whale. A little faster again, and it became a dolphin, until – back at normal speed – it reverted to a blackbird.

Turning into a wren

Andy played the same recording to me, altering its pitch as I listened with my eyes closed. Every sound was exactly as he’d described. When it had finished, I asked him to speed up a recording of an actual whale song. It sounded like a blackbird!

I am not going to attempt any scientific analysis of natural sounds here – what they mean, why they are as they are, and whether they are random or rational. For that I direct you to The Great Animal Orchestra by Bernie Krause.

Krause often refers to the work of British sound recordist Chris Watson. I have worked with Chris for years, and have heard many extraordinary things ‘before my very ears’.

For example, there was the day he turned me into a wren. I have the figure – small and dumpy – but Chris gave me the voice as well.

Practice makes perfect

A wren’s song is not long, but it is very fast, packed with notes and incorporating a characteristic trill. There is no way that I could whistle or sing it. Then Chris slowed it down.

What amazed me was that many of the notes swooped and whooped in the manner of a dolphin or a gibbon. What, to my ears, sounded like one note was in fact several.

The trill – unsingable for a human – became a slow ‘tuk katuk katuk katuk’ that I reckoned I could get my larynx around. And so I prepared to sing like a wren.

For half an hour I listened, learned and practised. Then Chris recorded me doing my slow-speed wren impression. He played it back and I sounded somewhere between a jazz scat singer and a human beatbox.

Then came the moment of truth: playing the recording back at wren speed. As Chris did so, the pitch became higher and higher. You only have my word for it, but it wasn’t half bad!

I was so confident that I perched on a gatepost, miming to the recording. At least one wren responded, but we drew the line at mating. I wasn’t in the mood.

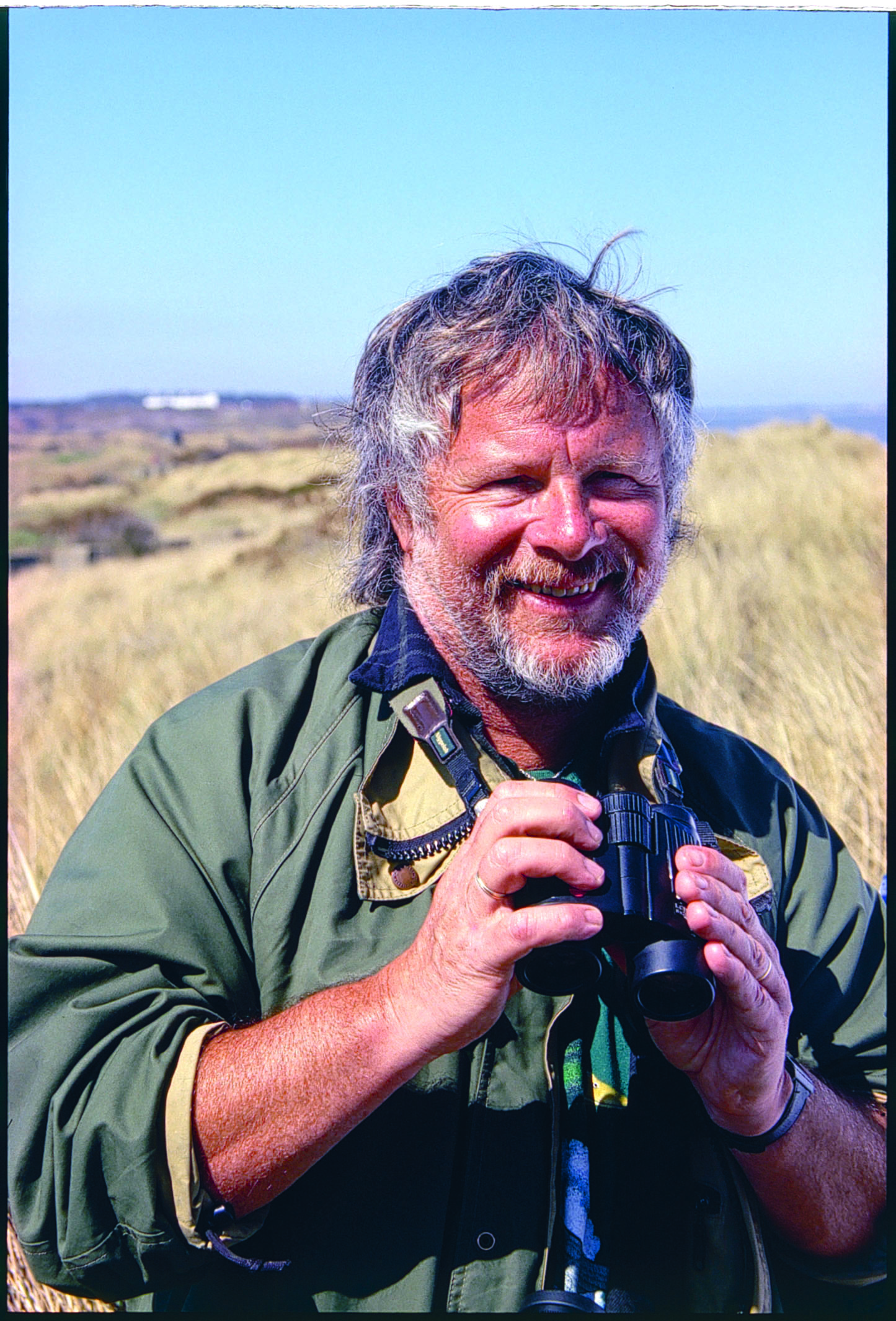

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column is a bit of both.