Birdies… eagles… albatrosses… is Bill talking wildlife, or golf? Well, both, actually.

Most naturalists – and birdwatchers, in particular – are rather fond of golf courses, especially if they are sited by the sea, which many of them are.

That’s because a lot of migratory birds make their first landfall on a golf course and, quite often, they find them to their liking.

The greens and tees may be a bit too velvety, manicured and possibly doused in insecticide, but the short-cropped fairways are much loved by wheatears, pipits and larks, while warblers and thrushes lurk in ditches and any available scrub or bushes.

What’s more, though landing in the rough may be a nightmare for golfers, it’s a joy not only for birds but also small mammals, wildflowers and insects, especially butterflies.

Indeed, while there are many golf courses that look as if they have been designed for nature, some of them actually have.

One May morning a few years ago I was given a tour of a holiday village in Suffolk by the environmental manager.

He showed me an area destined to become a golf course but which was also a nature reserve.

Islands of rough had been left undisturbed and, encouraged by a little management, were glowing with heath-loving wildflowers.

These included several common orchid species, many of which had lain dormant in the soil until the construction work had emancipated them.

If you hanker after rarer varieties, there are few better sites than Sandwich Bay in Kent – or, to be more specific, the fringes of Royal St George’s golf course, the sporadic home of the British Open and the permanent home of lizard orchids.

Wader wonderland

My most lavish experience of ‘life on the links’ was across the pond in the USA, at Walt Disney World in Florida.

The site encompasses an area almost the size of an English county, covered by woods and waterways that are much appreciated by the brazenly tame Florida birds such as herons, darters and ibises, plus the occasional alligator and three kinds of chipmunks – real, animated and actors in furry suits.

There are also loads of golf courses. One of them became my local patch for the week, with warblers and woodpeckers in the trees, kingfishers diving into what I assumed was a ‘water hazard’, and a feature that was clearly the ideal nesting beach for a small colony of least terns.

I wondered if they ever ended up incubating a stray ball instead of an egg.

Best of all I was there in the baking heat of late August so, every morning, the greens and fairways were drenched by a cascade of sprinklers that created an ideal habitat for migrant waders.

When the golfers arrived, they simply fluttered a few yards to another mini marsh. Both birds and golfers seemed oblivious to the danger of a hooked tee shot bringing down a semipalmated sandpiper – at which point surely no golfer could possibly resist saying: “I got a birdie at the 12th!”

Fairway takeover

But I see no reason why birders and golfers should not co-exist – unless a rarity is involved, as happened back in the 1980s in South Wales.

The bird in question was a little whimbrel (a whimbrel is like a curlew, only smaller; a little whimbrel is smaller still), normally found in Australasia and seen in Britain on only two occasions. Now that’s rare.

This little whimbrel was spotted within the bounds of Kenfig National Nature Reserve but, just before dark, it flew to roost on an adjacent golf course. The news spread like wildfire.

The twitchers of Britain arrived throughout the night from far and wide; before first light, several hundred of them were assembled – not in the reserve, where they were welcome, but at the end of the first fairway, where they weren’t.

Imagine the scene as, just after sunrise, the first golfer shuffled to the first tee, placed his ball on the pin, selected his driver and peered down the fairway – at which point 500 twitchers appeared over the horizon, plonked down their tripods and pointed binoculars and cameras right at him.

Even Rory McIlroy would have sliced his shot.

‘Eagle’, ‘albatross’ – why not ‘little whimbrel’? For some reason, the phrase has never caught on.

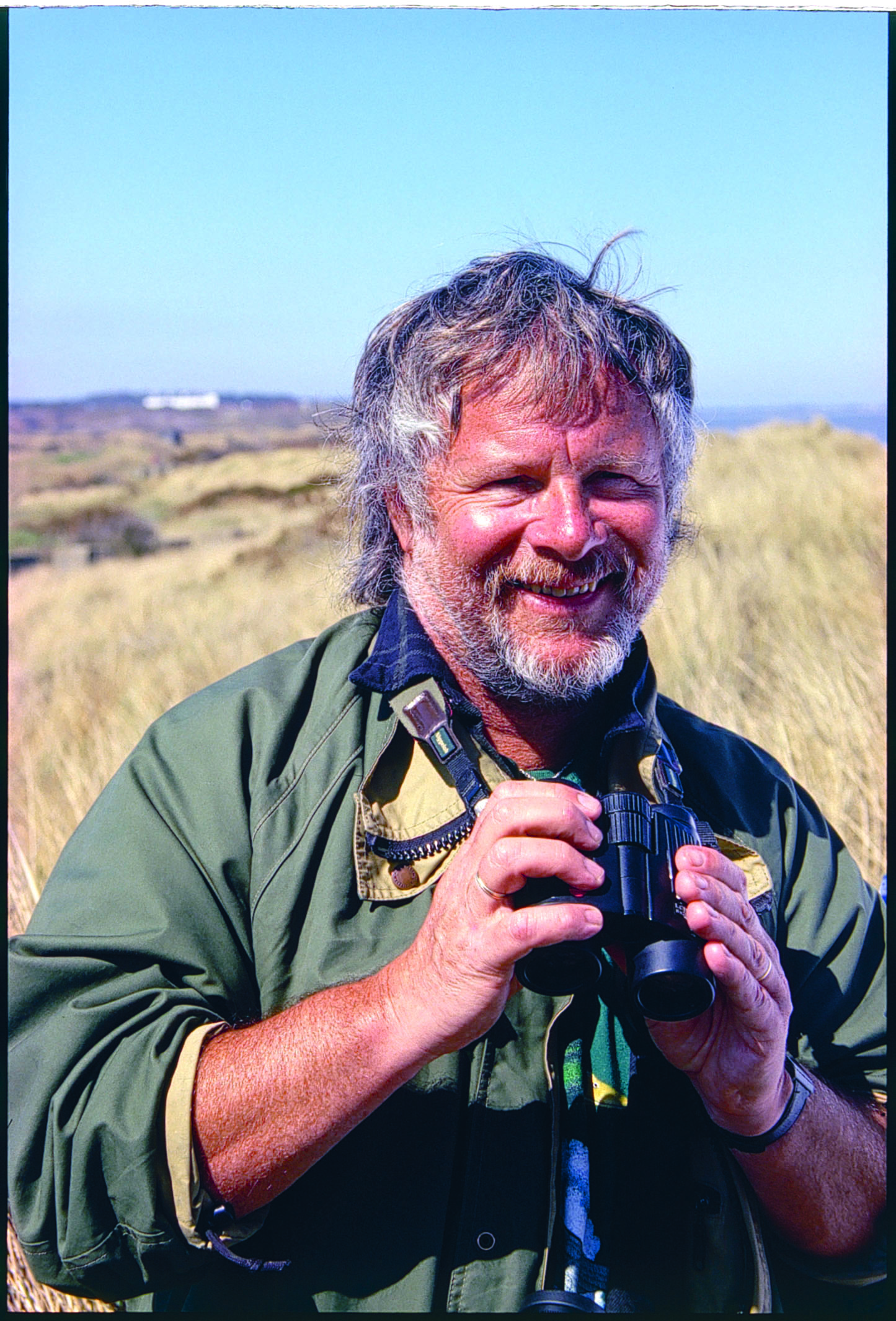

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column is a bit of both.