Buzzard numbers are soaring in Britain – we should celebrate the species’ success, not threaten it.

Several years ago, a friend of mine spent a weekend in Scotland. When he got back, he was excited about a bird he’d spotted, though he wasn’t confident about the species.

“Could we have seen a golden eagle?” he wondered.

“Where exactly were you?” I asked.

“In the Cairngorms.”

“Well, there are golden eagles there. What was it doing?”

“It flew across the road.”

“Are you sure it wasn’t a buzzard?”

“It was really big!”

Birdwatchers always say that if you see an eagle, but you’re not sure, then it’s a buzzard – in Scotland they call them ‘tourists’ eagles’. But when you spot an eagle, you know it’s an eagle.

My friend was deflated. His wife said, “Never mind, dear.” His daughter added, “I told you so!”

Success story

Since then, my friend has seen lots of buzzards, and he didn’t even have to go back to Scotland. He lives just north of London, where he now spots them most weeks.

He no longer mistakes them for eagles, though he does get them confused with red kites, whose numbers are also increasing.

Not so long ago both of these species were in trouble in Britain. In the late 1950s, there were only half a dozen pairs of kites, all deep in the Welsh valleys.

Buzzards were not quite so scarce, but they were very much birds of hills, mountains and moorlands – so much so that we all assumed they needed such specialised habitat to survive.

Holland heaven

Then, many years ago, I went to Holland – the epitome of flatness, with nary a hillock in sight. Here were thousands of geese and lots of buzzards – perched on posts, dawdling along dykes and, most incongruously, shuffling around in the grass feeding on earthworms.

It was clear that the birds needn’t be confined to moors and mountains. So, if they were happy in Holland, why not in England?

Catholic diet

And now – thanks to less prejudice, and the reduced use of poisons and pesticides – ‘tourists’ eagles’ are proliferating. Another reason for their success is that they are not fussy eaters. Which is just as well, because they are hardly impressive hunters.

They can’t perform the deadly dives of a peregrine nor the lightning interceptions of a sparrowhawk. It says a lot about their lack of skill that much of their ‘live’ food (rabbits, pigeons, etc) is already ill, injured or dead.

But buzzards do risk their own lives by swooping on roadkill, along with other scavengers.

The danger of success

But often when a species is booming it becomes a victim of its own success. Magpies and sparrowhawks have been accused of killing songbirds, parakeets stand accused of stealing nestholes, and now buzzards are accused of taking pheasants!

I could not believe it when the Government announced that it was planning a trial project that would sanction the destruction of buzzards’ empty nests to displace breeding birds, either by blasting them with a shotgun or poking them with a stick.

What’s more, buzzards would also be “removed” (how?) and taken into captivity (where?).

So I was not at all surprised when an enormous protest was marshalled by organisations such as the RSPB, The Wildlife Trusts and the League Against Cruel Sports.

But I was surprised when, only a couple of days later, Defra said that the trial had been withdrawn. Is this the fastest U-turn the Government has made so far?

So where does that leave things? The buzzards seem safe, for now at least.

Meanwhile, millions of pheasants are captive-bred every year, only to be blasted out of the sky in the name of ‘sport’. Many of the birds are so heavy that they can hardly fly, so are splattered by cars and lorries on country roads, ending up as buzzard food anyway.

I will leave the last word to my friend: “If they really want to save pheasants, they should ban traffic!”

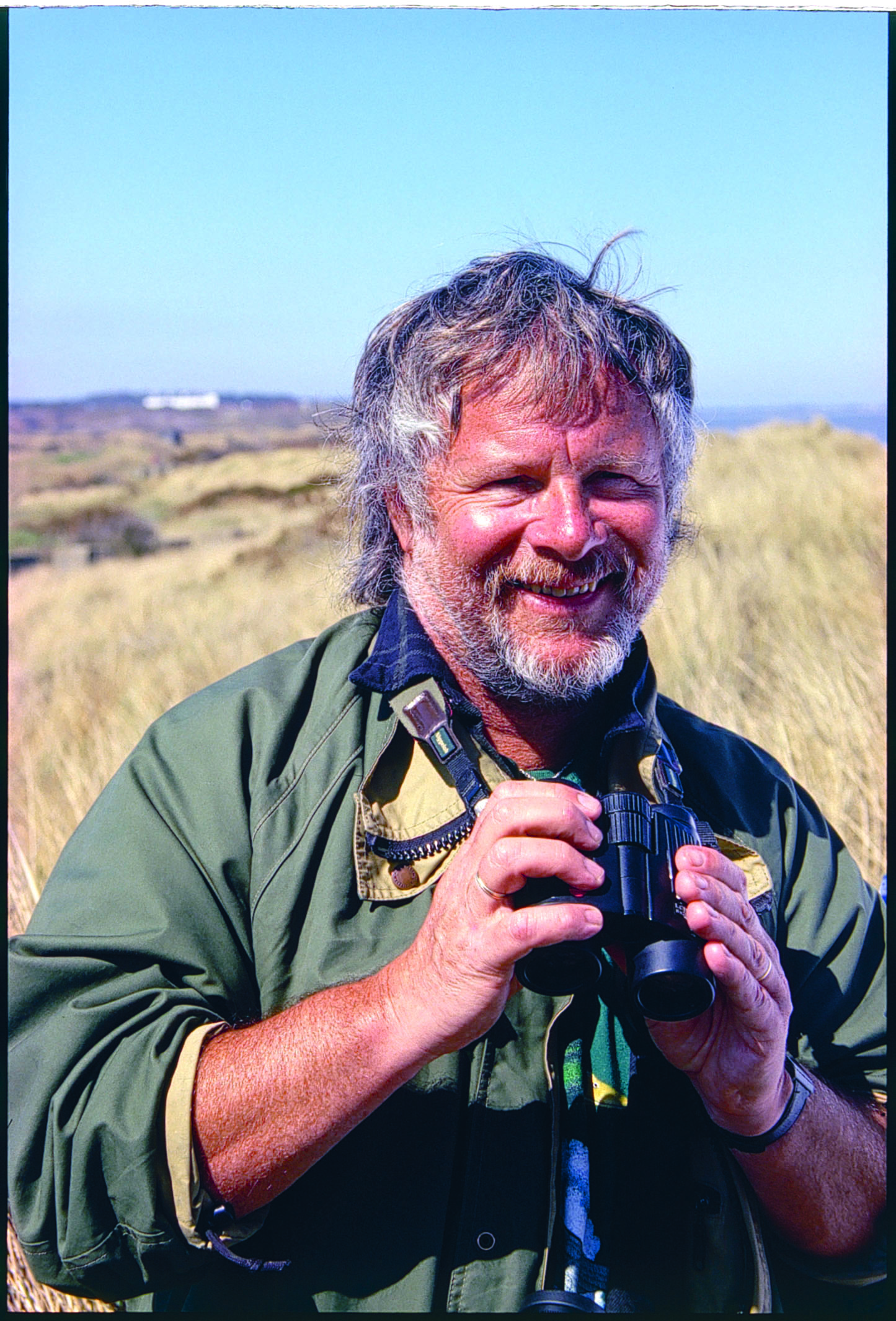

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column is a bit of both.