YOU DON'T NEED to study the living world for long to realise that there are exceptions to almost every rule about nature you can think of. Just when you believe you've got it all neatly pigeonholed, along comes an organism that doesn't fit.

What's the difference between plants and animals?

Take the distinction between plants and animals – it seems so simple. Animals have acute senses and flexible, muscular bodies coordinated by nervous systems that allow them to find food and eat it.

Plants, built from rigid cells and rooted to the spot, simply bask in the sun, gently photosynthesising and growing at a leisurely pace. But evolution is endlessly inventive and, despite last sharing a common ancestor with animals about two billion years ago, plants have independently evolved some remarkably animal-like traits.

Here, courtesy of the coincidences that only endless shuffling of genes can create, are 10 truly exceptional specimens from the vegetable kingdom.

Meet the plants that behave like animals...

Sundew

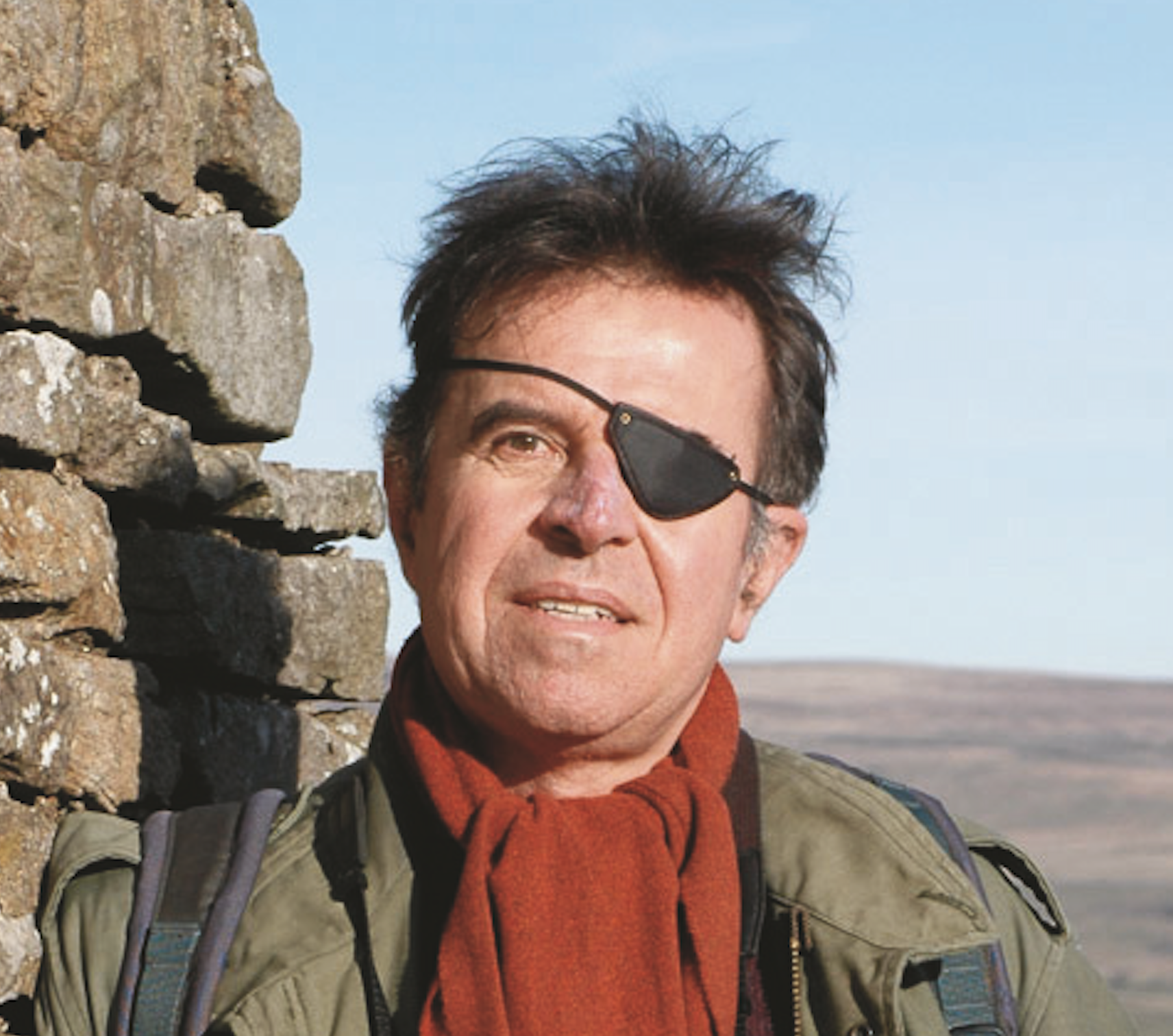

Sparkling hairs that become a vegetable stomach

Getty Images

It was Charles Darwin who first referred to the leaves of the insectivorous round-leaved sundew as a vegetable "stomach". He was besotted with these beautiful carnivorous plants, found around bogs and marshes. First a fly becomes stuck in the sticky secretions of their glittering glandua hairs.

Then the unfortunate insect's desperate struggle cause surrounding hairs to curl towards it. Finally the whole leaf folds itself over the exhausted victim and, inside the vegetable stomach', digestive enzymes (very similar to those in our own stomachs) drench and slowly dissolve their prey.

Skunk cabbage

A plant with inner warmth

Warmed by the summer sun, chilled by winter winds, plants are at the mercy of the weather. Their fluctuating temperature usually matches that of their surroundings, but there are a few species that, like warm-blooded birds and mammals, can generate their own internal heat.

One of these is the skunk cabbage. In the frozen sub-Arctic, its inflorescences (flower clusters) bloom very early by using heat generated from the weird spadix (club-like structure bearing the flowers) to melt their way through the snow.

This biochemical heat-generating mechanism is very animal-like. Respiration breaks down food (starch produced by photosynthesis in a plant) and releases energy – all in the form of heat in the spadix.

Witchweed

A vegetable vampire

Above ground all looks innocent enough – just a group of pretty, spiky-leaved wallflowers surrounding a maize plant – but below ground something sinister is happening

The blooms belong to witchweed, a vampire of the plant world. It has no roots of its own – soon after its seed germinates, it plugs itself into the nearest host plant and develops a plumbing connect with its victims rot system, called a haustorium. Then it starts sucking out water and minerals. Witchweed is a devastating weed of African cereal crops that can bring ruin to subsistence farmers.

Mirror orchid

"Hello petal!" Sex sells..

The orchid genus Ophrys contains many species that resemble female bees and wasps in order to entice male insects to attempt to mate with them – thus pollinating the flowers. Ophrys speculum from the Mediterranean is a prime example: it even has a blue patch that looks uncannily like light reflected from the folded wings of a wasp.

But there's another hidden sexual attractant – the orchid has evolved a scent that exactly mimics the come-hither aroma of female wasps, provoking a sexual frenzy in males. Browse the perfume counter in a department store and you'll be left in no doubt that fragrances are potent sexual signals – an evolutionary conclusion that Ophrys and its enslaved wasps reached millions of years ago.

Rafflesia

Has something died around here?

One drawback of being a rare plant hidden deep in a forest, flowering once in a blue moon, is that it's hard for the pollinators that you rely on for seed production to find you.

What better way, then, to attract flies than to smell like a corpse? Rafflesia, a parasitic plant that spends its entire life-cycle hidden inside tropical lianas and only sporadically advertises its presence by producing the world's largest flower, releases the disgusting aroma of putrefying meat.

It even has the visual and tactile qualities of bloody, wrinkled flesh. Lovely – if you're a fly.

- Weirdest plants in the world: Discover 9 of the planet's wackiest flora

- It reeks of rotten flesh, blooms for 24 hours and heats itself up – meet one of the world’s most fascinating plants

Toothwort

In floods of tears

Charles Darwin, one of the most acute observers of nature ever, was the first to notice that the soil around toothwort – a parasite of hazel tree roots – is always moist, even in a drought.

Toothwort's survival depends on sucking water and nutrients from its host. In most plants, evaporation from leaf surfaces pulls a continuous current of water along channels inside them, but toothwort has no leaves – just a spike of waxy flowers. So how does it keep its essential fluids flowing? It exudes a nonstop trickle of 'tears' from glandular pores called hydathodes into the surrounding earth.

Sensitive plant

The fast-moving plant that fights back

Imagine you're walking down the street, on your way to a restaurant, and you step on the trap doors over a cellar and they open up beneath your feet. That's the feeling that herbivorous insects experience when they crawl onto a Mimosa pudica leaf in the expectation of dinner – only to be unceremoniously dumped on the ground.

Each leaflet is touch-sensitive: within a second or two of tactile stimulation it collapses, triggering a 'domino effect among nearby leaflets and then the leaves themselves. Truly, some plants can move as fast as animals.

Maidenhair tree

The giant sperm of a living fossil

Sexual reproduction evolved in water, where male sperm can swim to female egg cells. Land-based sex in mosses still operates on the same principle – on rainy days, their moist surface swarms with millions of microscopic sperm, frantically swimming to find a moss egg cell.

It's wasteful – millions fall by the wayside, and it only works in wet weather – so more advanced plants such as the 'living fossil' maidenhair tree Ginkgo biloba deliver sperm in a more sophisticated package. A pollen grain bursts near an egg cell, releasing just two giant sperm that complete the last millimetre of the journey, aided by thousands of beating ciliary hairs.

Broad bean

Red-blooded roots

Evolution, the great improviser, reuses ancient molecules in new ways as circumstances demand. Plant roots might be the last place you'd expect to find blood pigments, but if you cut open a bacterial root nodule you'll find a bright red stain that looks suspiciously like blood.

This is leghaemoglobin – the vegetable equivalent of the haemoglobin pigment in our red blood cells that transports life-supporting oxygen. But, in bean root nodules, oxygen acts as a poison. It inhibits bacterial nitrogen-fixing enzymes – the plant's built-in fertiliser factory that converts atmospheric nitrogen into nitrates used for growth. The solution? Leghaemoglobin locks the oxygen away where it can do no harm.

Strangling fig

Squeezed to meet you – the boa constrictor of the plant world

If trees had nightmares, strangling figs would surely loom large. The life of a strangling fig starts innocently enough: a seed in a bird dropping germinates in the angle of a branch, high in the tree canopy. Then an aerial root slithers over the branch and grows downwards until it reaches the soil.

Soon others follow crisscrossing and joining on their way down, while their leafy shoots develop high above. Eventually the encircling cylinder of expanding aerial roots begins to squeeze its victim, slowly, over decades, all the while monopolising nutrients from the soil until the starved host tree dies and rots away. Only the scaffold of strangler roots is left to mark its passing.

Surely worthy of a place on our weirdest trees list?

Discover more weird flora amnd other plant facts

- Weirdest plants in the world: Discover some of the planet's wackiest flora

- Hydnora africana: what it is, when it flowers and how it survives underground without roots

- Are there any albino plants?

- Do plants use warning colours?

Top image: Getty Images