Daffodils flowering in December, oak trees coming into leaf in March and swallows arriving before spring should properly have sprung – we’ve all noticed changes such as these.

Less well-known is that climate-change-linked phenomena are also happening beneath the surface of our lakes and rivers, unheralded.

As an example of spring’s now untimely arrival below the water line, Stephen Thackeray, of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH), cites how perch in Lake Windermere are spawning earlier. “It’s only a few days each decade, but if this is sustained over a long period it can be enough to disrupt relationships between species.”

The appearance of the perch larvae moves out of sync with the seasonal proliferation of the plankton they feed on, leading to poorer survival rates.

Thackeray is in little doubt that this is being caused by long-term changes in our climate, which also probably contributed to the extremity of this summer’s prolonged heatwave.

But while provisional Met Office records suggest air temperatures in July were 2.2˚C above the 1981–2010 average, the surface water in Windermere reached 22˚C, 4˚C higher than the long-term average. This, Thackeray says, will impact species such as Windermere’s Arctic charr, a relative of salmon and trout.

“They become stressed at anything above 15˚C, so this is far above their thermal range,” Thackeray explains. They can dive (to 64m in Windermere) to cool down but the habitat available to them is reduced.

Windermere's Arctic charr become stressed at anything above 15˚C

The problem is compounded as warming temperatures also fuel the growth of blue-green algae – cyanobacteria – which sinks to the bottom and decomposes, depleting oxygen levels. Over the summer, these had decreased to below 7mg per litre, close to the charr’s limit of 5mg per litre. When it breaks down, the algae also releases toxins that can poison livestock, pets and people.

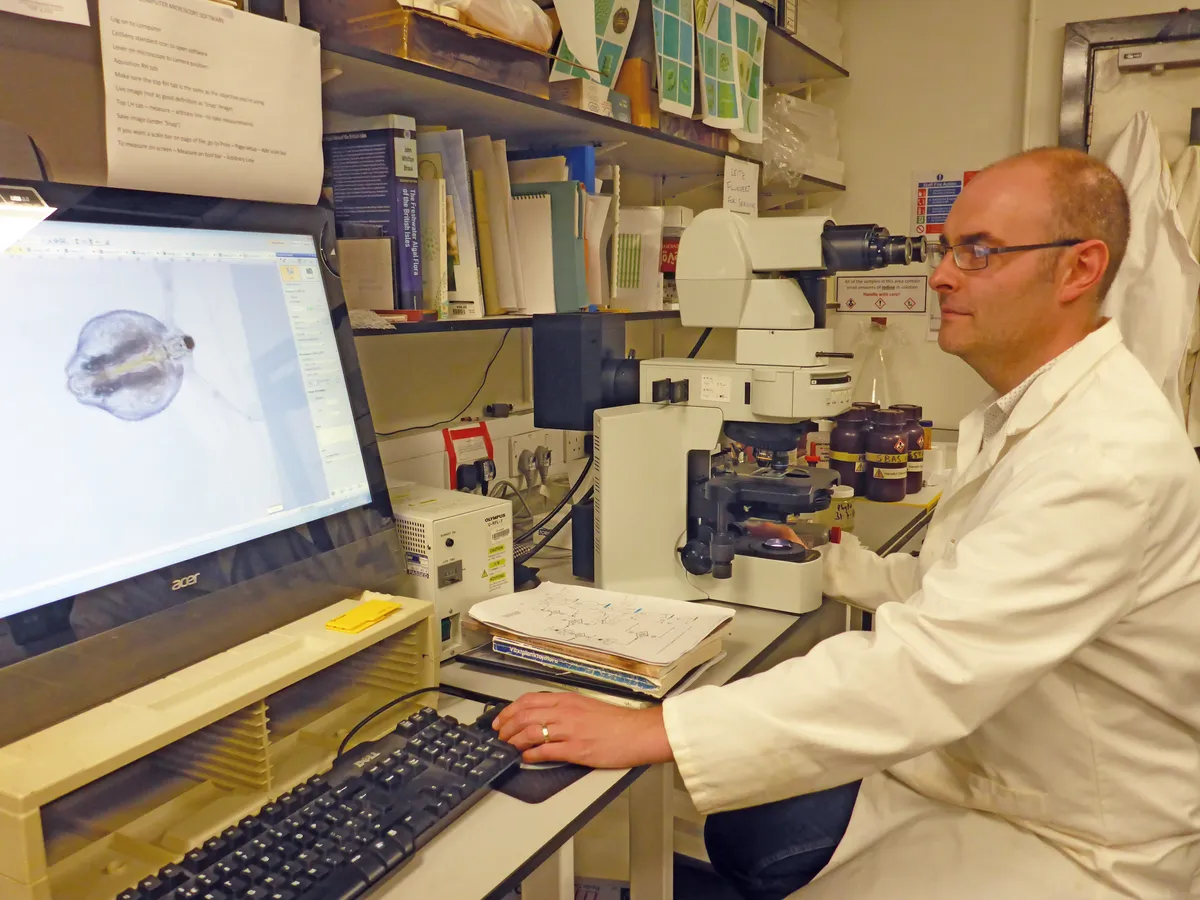

Fieldwork for Thackeray and his team involves taking water samples, recording temperatures and oxygen levels and analysing levels of nutrients such as phosphorus. He is also trying to devise new ways to understand these ecosystems using satellite imagery to spot freshwater algal blooms – CEH recently launched an app, ‘Bloomin’ Algae’ so the public can join in helping with this.

Biodiversity decline has been more rapid in freshwater systems than in terrestrial or marine habitats. “The Office for National Statistics (ONS) values our freshwater systems at £39.5bn,” he says. “But what do the impacts on them mean for us?” If anyone is going to find an answer, it’s most likely to be Thackeray himself.

To find out more, read Stephen’s blog.