“Bond watched, fascinated. He guessed it was a boa of the Epicrates family, attracted by the smell of blood. It was perhaps five feet long and quite harmless to man.”

This excerpt is from The Man With the Golden Gun, when James Bond is in the middle of a shoot-out in a swamp in Jamaica with a bad man called Pistols Scaramanga. He also observes land crabs: “There were occasional remnants of their shells, victims of big birds or mongoose.”

- Fraud, thief, cold-blooded killer: Why the famous naturalist and British spy who inspired James Bond was not all he seemed

- Was 'M' in James Bond real? Meet the real-life secret spy called 'M', who would have rubbed shoulders with Ian Fleming

There’s no getting away from it. James Bond is a naturalist and his creator, Ian Fleming, was a nature writer. Nature keeps cropping up in his 11 Bond novels and in his two collections of short stories, often in sumptuous detail. And you can always tell a bad man because he kills wildlife for fun. In that boggy battle, Scaramanga has already demonstrated his badness by shooting a turkey buzzard.

Fleming had a house in Jamaica. He called it Goldeneye, after the duck, which is in itself a giveaway. It was Fleming’s habit to keep on his breakfast table a field guide entitled Birds of the West Indies. I have a copy myself, bought for a visit to Barbados in 1990. The name of the author is Bond. James Bond. “I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find,” Fleming said. “James Bond seemed perfect.”

Fleming wrote all his Bond books at Goldeneye, starting with Casino Royale in 1952. It’s a plain name all right, or it was then – but perhaps the fact that birder Bond showed Fleming so many wonders was a factor in his choice.

Agent Bond is a cipher. He has very little character, only a number of distinguishing features that Fleming notes with the meticulous care of someone writing a field guide: single-breasted dark blue suit, Sea Island cotton shirt, black silk knitted tie and black moccasins (he “abhorred” laces). The books brilliantly invite readers to fill Bond out by way of their own fantasies. And time and again Fleming uses nature to paint a scene: if it’s peaceful you can guarantee lethal action in a page or two; if it’s dangerous Bond will find his best qualities to deal with it. So let’s put Bond under surveillance as a secret naturalist, and examine Fleming, who – for your eyes only – is a clandestine nature writer.

Fleming doesn’t get down to nature all at once. Most of the action in the first Bond novel, Casino Royale, unfolds – unsurprisingly – in a casino. But in the elegiac final sequence, Bond, recovering from horrific torture with a carpet beater, strips naked and walks along the beach, finally at peace with the sea, nature and himself.

Marine life in James Bond

The marine environment – both above and below the surface – crops up repeatedly in Fleming’s writing. Goldeneye is located right on the beach, the reef comes close to the shore and Fleming could just pull on his rubber mask and walk into the sea every day. The spell of that reef captivated him his entire life. To snorkel over coral is perhaps the most dramatic experience of biodiversity on the planet, and Fleming adored it. Undersea creatures star in his second novel, Live and Let Die, which sees Bond caught by an octopus and surrounded by barracudas. The Robber (bad) shoots a pelican “for practice” and Bond’s friend Felix Leiter loses his leg after being thrown into a shark cage.

In Thunderball, we’re back underwater and back in the Caribbean. There are descriptions of sea urchins, sea eggs, sea hares, butterflyfish and angelfish. And a shark: “Bond watched it carefully as if he had been an underwater naturalist.” The climax is an undersea battle in which the bad man attacks Bond with an octopus.

- Like to dive? Check out these extraordinarily beautiful underwater statues teeming with wildlife

- Best wildlife snorkelling and diving sites in the world

It’s in Dr No, however, that Fleming really lets himself go. This book, set in Jamaica, is a feast of nature, and the adventure begins with the misfortunes suffered by roseate spoonbills – “pink storks”, as M grumpily calls them. Dr No, who so cruelly abused these fine birds, makes a living from guano deposited by cormorants. But the story’s heroine is nothing less than a nature goddess: Honeychile Rider emerges from the sea naked, bearing in her hands seashells, which she identifies as Venus elegans. This is a real species, though the name is now obsolete. In the film adaptation, Ursula Andress as Honey famously makes her entrance wearing a white bikini and carrying two conches. She and Bond are pursued through mangrove swamps and taken captive. Honey faces an ordeal with land crabs; Bond duels with a giant squid.

Back on dry land, Fleming is fascinated by invertebrates. Bond notes in The Man With the Golden Gun that being an agent is like being an entomologist: it’s so easy to miss something of real significance while you’re looking out for something else. Invertebrates appear throughout the novels – and the deadlier, the better. Dr No’s minions sneak a deadly centipede into Bond’s bed; From Russia With Love opens with a peaceful scene in a garden with a dragonfly (the relaxed man in this gentle landscape is revealed as an assassin); and Diamonds are Forever is bookended by vignettes of the invertebrate life of West Africa.

The story opens with a scorpion – a Pandinus scorpion, we learn – and a beautifully observed account of the creature hunting a beetle: “Slowly the sting slid home into its sheath and the nerves in the poison sac at its base relaxed. The scorpion had decided. Greed had won over fear.” A bad man kills the scorpion and, in the final sequence, we have a column of driver ants. The same bad man kills as many as he can before the even badder man arrives.

Deadly flora and fauna

Bond’s life is hard and he has experienced much death, guilt and loss. In You Only Live Twice he is close to breakdown. He sits in Regent’s Park looking at insects and resolving to read Maeterlinck’s The Life of the Bee. Then he perks up and is off to Japan, where he learns about a garden exclusively planted with poisonous plants – this chapter is called Slay It With Flowers. We then get two lists: six different kinds of plant poison and 22 species of poisonous plant. Bond enters the deadly garden, noting crickets, dragonflies and toads. He reflects, species by species, on which snakes “really went for a man”.

Fleming brought his fantasies to life with the inspired use of detail. Kingsley Amis, in The James Bond Dossier, refers to this as “the Fleming effect”. Wildlife detail is part of that – but its frequency betrays an emotional delight that appears to have more resonance for the author than his descriptions of gadgets and fast vehicles, such as the boat that operates on “the Shertel-Saschenberg system”.

James Bond: secret ornithologist

Neither Bond nor Fleming can ignore a bird. Before his epic match with Goldfinger, Bond is exhilarated and encouraged by the singing of larks on a golf course. The Spy Who Loved Me is set in the North American woods and features a small songbird known as a bobolink and the call of a mourning dove. In On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Bond finds himself in the mountains, where he observes Alpine choughs and snowfinches – the white-rumped snowfinch (actually a sparrow) is only found at altitudes of more than 1,500m.

In the same novel, Bond visits M on Christmas Day and finds him painting “an extremely dim little flower”. M tells us it’s an autumn lady’s tresses orchid – and then delivers a brief lecture on the plant’s symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal fungi. Orchids also pop up in Moonraker. It’s a claustrophobic and mostly indoor adventure but features one golden afternoon (horror to follow shortly) when Bond and special officer Gala Brand embark on a lovely walk. Gala picks a bee orchid and Bond teases her, claiming that flowers feel pain.

For Your Eyes Only is a collection of five short stories. When established authors try this sort of thing they usually have a bit of fun with new ideas, writing with a freedom unavailable over the longer course. The first story, From a View to a Kill, is set in a French forest with red squirrels, wood pigeons, thrushes, hedge sparrows and bees. At the end, Bond invites fellow agent Mary Ann to look at a bird’s nest. The title story begins with hummingbirds, the red-billed streamertail, the national bird of – yes – Jamaica. Later, Bond walks through the woods on the US-Canada border, the bad man shoots a kingfisher and Bond meets a minor nature goddess.

The Hildebrand Rarity, the last in the collection, is a bravura piece of nature writing. The story is about the search for a rare fish, and the description of a reef’s fish responding to poison administered by the bad man is a tour de force: “Several fish looped the loop crazily and then fell like heavy leaves to the sand. The moray eel came slowly out of the hole, its jaws wide. It stood carefully upright on its tail and turned over on its back and gently tipped sideways…” Bond and Fleming are equally horrified by the destruction of nature.

Octopussy is another collection of short stories, published posthumously in 1966, two years after Fleming’s death. Different editions have different numbers of tales, the top count being four. One of these involves a meeting at the reptile house in Central Park Zoo. In another, set in Berlin, Bond identifies wildflowers including rosebay willowherb, dock and bracken. In a third, a character meeting Bond “felt as if he had touched paws with a Gila monster”, a venomous lizard found in the United States.

The title story takes us once more beneath the waves of a Jamaican beach, and tells of Major Dexter Smythe’s disgrace and his obsession with an octopus. Smythe, a self-pitying drunk, loves the creatures of the reef and calls them his “people”. It’s clear that Fleming, minus the mawkishness, feels the same.

“A novelist writes what he is,” said X Trapnel, a fictional novelist in Anthony Powell’s 12-volume series of novels A Dance to the Music of Time. Fleming, indeed, writes what he is: a fantasist with a deep love of nature; no expert but a massive enthusiast. In his work nature sometimes brings peace, sometimes glorious adventure and breathless excitement: we can all relate to that. A nature sequence frequently reveals Fleming’s passion. Sometimes it even brings a touch of humanity to Bond.

Nature affords the James Bond books depth and, with it, the sweet illusion of plausibility. Wildlife enriches every one of them, just as it enriches our own lives.

Discover more fascinating historical figures

- Who were the real Durrells – and what on earth happened to them all? Was it all guns, goats and Greek sunshine?

- Who was the real James Herriot? Meet the man who became the world's most famous - and beloved - vet

- From isolation to icon: How Hannah Hauxwell's life in the Yorkshire Dales became a worldwide sensation

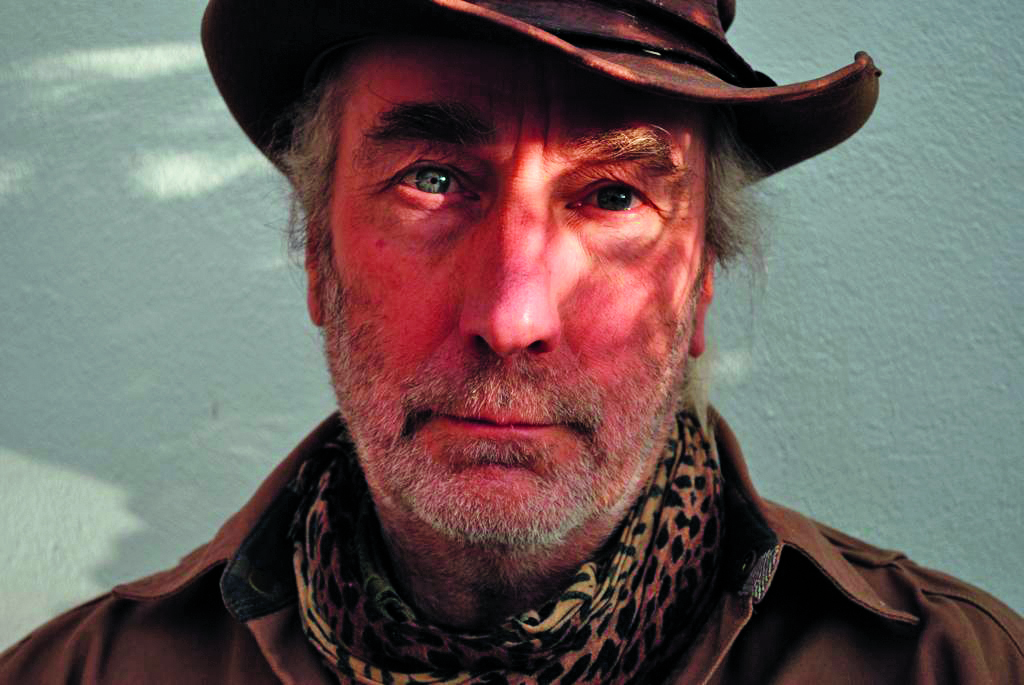

Main image: Ian Fleming on the beach near Goldeneye, his Jamaica home, in 1964/Getty