The achievements of many women in history have been overlooked, with environmentalists and naturalists no exception. This guide features ten inspiring and influential women in history who had a lasting impact on wildlife and nature, and you can learn more about a selection of 19 extraordinary, trailblazing women whose work has helped to shape the history of ornithology in this article by Jo Wimpenny.

Queen Hatshepsut (1479– 1458 BC)

Described by Egyptologists as "the first great woman in history of whom we are informed", Hatshepsut was one of the most successful pharaohs of Ancient Egypt. She was also a keen botanist.

Reigning for longer than any other indigenous Egyptian woman she was also only the second known female pharaoh.

Hatshepsut was responsible for first ever recorded expedition to collect living plants. She sent out five ships with the order to gather valuable plants, animals, and precious goods from the land of Punt on the northeast African coast.

These ships returned bearing 31 live myrrh trees- the first recorded foregign tree transplantation attempt, which Hatshepsut planted in the courts her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

Inscriptions at the temple celebrate the expedition and successful transplantation.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179)

Hildegard of Bingen, also known as St. Hildegard was a German Benedictine abbess and scholar. She was a true polymath, creating renowned works on the topics of philosophy, musical composition, spirituality, cosmology, herbology, medicine, biology, and natural history.

For Hildegard her love of God and her love of nature were intrinsically entwined, as she considered that the Divine was revealed in and evidenced by the beauty of the natural world. Her writings on this concept and others led to her wisdom being well-known and sought by the nobility throughout Europe.

Her writings on natural history include Physica, a series of 9 books detailing the scientific and medicinal properties of plants, animals, and stones.

Her theories on the healing powers of many of these subjects may not have lasted the test of time, but her intense fascination with the natural world and its effect on humans is certainly to be celebrated.

She is remembered as the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647- 1717)

An artist and a gifted entomologist, German-born Maria Sibylla Merian was one of the first European naturalists to observe insects directly.

From a young age Maria would collect and draw the insects from her garden, and eventually started a caterpillar collection so that she could observe their transformation into butterflies.

“I spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silk worms in my home town of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed” she wrote.

This fascination with caterpillars led her to publish “Caterpillars, Their Wondrous Transformation and Peculiar Nourishment from Flowers” in 1679. Her work was pairsed for its scientific accuracy and meticulous attention to detail.

Her magnum opus was Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. Published in 1705 this beautiful book contained 60 large coloured plates, some of the first coloured images of the New World, depicting the tropical insects she studied on an expedition to Dutch Suriname.

This work has been credited with inspiring generations of naturalist illustrators and recognised as a significant contribution to the field of entomology.

Mary Anning (1799 –1847)

Responsible for some of the most significant fossil finds of the 19thcentury and in doing so, contributing greatly to the understanding of prehistoric life on Earth, Mary Anning was nonetheless largely excluded from the scientific society of the day due to her sex.

This was a time when women weren’t even allowed to vote, let alone attend the meetings of learned men at the Geological Society, or gain full credit for their scientific discoveries.

She was also forgotten by history until relatively recently. Happily, her remarkable accomplishments are now garnering more interest and recognition, and in 2022, a statue of her was erected in Lyme Regis. The campaign for a statue was launched in 2018 by a Dorchester schoolgirl called Evie after a fossil-hunting trip.

Mary was born to a poor family, and as such was deprived of a formal education. She was however lucky on one count – that she was born and lived on the Jurassic Coast in Dorset, an incredibly rich source of animal fossils.

Her father taught her how to look for and clean the fossils they found along the beach. He would sometimes sell these fossils, and after his death the young Mary continued to do so.

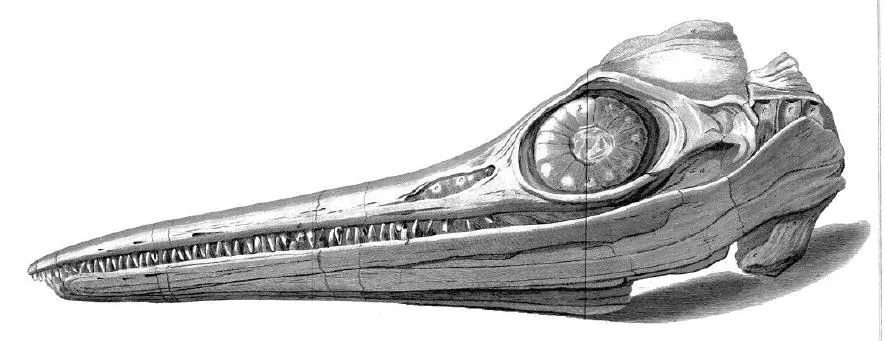

In 1811 the 12 year old Mary and her brother Joseph discovered the strange skull of what was later described as the first known ichthyosaur. Mary painstaking searched for and dug out the rest of the 5.2-metre-long skeleton of the marine reptile.

In 1823 Mary discovered and excavated the first complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus. This extraordinary find was disputed by eminent palaeontologist Georges Cuvier, and a special debate was held at the Geological Society to discuss it. Mary was not invited to this meeting, but Cuvier conceded his mistake and acknowledged that the find was genuine.

Although she was respected by and corresponded with some of the leading palaeologists of the time, she was often not credited at all in the scientific articles written about her finds.

Beatrix Potter (1866-1943)

Although best known as the creator of such beloved characters as Peter Rabbit and Jemima Puddleduck, Beatrix Potter was also a very keen naturalist, fascinated by fungi in particular.

Potter was a prolific artist, with a particular passion for botanical subjects. First drawn to them by their beautiful colours and great variety, over time she became more and more interested in fungal specimens she was reproducing in watercolours.

She began to collect mushroom specimens herself, observe them under her microscope, and create more meticulous representations.

She drew separate cross sections showing the attachment of the gills and the stem, depicted the various developmental stages, painted the fruiting bodies and the spores. The result was artistically beautiful but highly scientifically accurate and informative illustrations.

In creating these images, she became curious about spores and how they germinated. Though not the first to do so, she conducted detailed experiments into spore germination and post-germination development.

This led to her presenting her paper “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae” to the Linnean Society.

At the time the society did not admit female fellows, so she was not present at the meeting discussing her paper. Unfortunately, the paper was never published and no record of it exists today.

Although modern mycologists debate the innovative nature of her research, there is agreement that her detailed drawings were of later use in identifying mushrooms, and as such were an important contribution to the study of fungi.

Janaki Ammal (1897- 1984)

Sometimes called “the first Indian woman botanist,” Janaki Ammal made substantial contributions to the study of plant chromosomes and botanical geography, and yet her name is largely unknown outside her field.

After graduating with Honours in Botany in her native India Ammal travelled to Michigan to continue her studies. She went on to become, arguably, the first woman ever to obtain a PhD in botany in the US. These accomplishments were all the more remarkable at a time when literacy rates amongst Indian women was less than one percent, and fewer than 1,000 women in total were enrolled in education above the age of 16.

Ammal later moved to the UK, where she joined the renowned John Innes Institute and begun a lifelong and incredibly fruitful collaboration with famed biologist C D. Darlington. Together they wrote and published 'Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants’ which remains a key text for plant scientists to this day.

One of Ammals greatest accomplishments was her work on sugarcane crossbreeding. She crossed dozens of plants to determine which hybrids yielded the highest sucrose content. The result was the very sweet sugar that we use today.

Later in her life Ammal was also responsible for saving one of the last undisturbed swathes of forest in her home country and the vast biodiversity it contained. She used her sway as a respected scientist to lend her voice to a campaign called ‘Save Silent Valley’ which aimed to halt a hydroelectric project which would flood the forests there.

Using her careers worth of scientific knowledge, she spearheaded an effort to survey and record the chromosomal makeup of the trees in Silent Valley, in order to preserve the botanical knowledge held there if the flooding went ahead. Fortunately, the campaign was a success and the government abandoned its plans, due in part to her strong voice of opposition.

Barbara McClintock (1902-1992)

Barbara McClintock is perhaps best known as the discoverer of ‘jumping genes’ or transposons, sequences of DNA that move (or jump) from one location in the genome to another. For this pioneering work she received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983. She remains the first and only woman to receive an unshared Nobel Prize in that category.

McClintock came to her great discovery through a fascination with the genetic make-up of maize plants. She studied heritable traits in maize plants – those characteristics that are passed down from one generation to the next – for example the beautiful array of colours that the kernels come in.

Through studying how these traits are passed down and linking them to changes in the maize chromosomes she realised that genetic elements can sometimes change position on a chromosome.

She also demonstrated many other fundamental genetic ideas through her work with maize, including the notion of genetic recombination by ‘crossing-over’. This is the idea that genetic material can ‘shuffle’ between chromosomes upon sexual reproduction, and is the reason that we have different combinations of characteristics than either of our parents.

Although largely disregarded at the time, these findings were hugely significant for our understanding of genetics. McClinktock’s work did however gain greater acclaim in the 1960’s and 70’s after other scientists had confirmed the genetic mechanisms that she had demonstrated in her maize research.

Barbra McClintock could well have been prevented from making these ground-breaking discoveries due to the sexism of the time however. Her mother nearly prevented her from attending college due to fears that it would make her ‘unmarriageable’, and she was later only able to carry out her pioneering research at Cornell due to outside funding, as the university would not hire a female professor.

If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off... no matter what they say.

Barbara McClintock

Rachel Carson (1907 -1964)

Considered by many to have kick-started the modern environmental movement, Rachel Carson, a marine biologist and conservationist, is best known as the author of the hugely influential Silent Spring.

In this pioneering work Carson questioned the right that humans have to gain mastery over the natural world, specifically through the use of chemical pesticides.

Underlying all of these problems of introducing contamination into our world is the question of moral responsibility -- responsibility not only to our own generation but to those of the future.

Rachel Carson

She was moved to write Silent Spring after learning about the growing widespread, and often undiscerning, use of powerful pesticides such as DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), and the resulting environmental problems, such as declines in bird populations.

Although met with fierce criticism from the chemical industry, who sought to discredit her as a hysterical woman and a communist, Silent Spring garnered positive reviews from the public and scientists alike. Due to this it brought about many changes in US pesticide policy, including a complete ban on DDT for agricultural uses.

The book has also been credited for bringing environmental concerns to the American public, a legacy that persists to this day, and a movement that resulted in the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Wangarĩ Maathai (1940- 2011)

The first African woman to receive a Nobel Prize, as well as the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctorate degree, biologist and environmental activist Wangari Maathai was truly a trailblazer.

Born in rural Kenya to a farming family, Maathai unlike many girls at the time received a formal education, first at the local primary and secondary schools, then in 1960 she was awarded a scholarship to go to university in the United States.

She attended Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas, where she attained a degree in biology. Two years later she completed a masters in biological sciences from the University of Pittsburgh.

She later returned to her native Kenya, where she completed her PhD in veterinary anatomy at the University of Nairobi. Professor Maathai became the chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and an associate professor. In both cases, she was the first woman to achieve those positions in the region.

Through her work with the National Council of Women of Kenya, an organisation in which she was very active, Maathai became interested in the idea of community tree-planting. She proposed this as a way to reduce poverty whilst conserving the environment. This idea became the Green Belt Movement, a grassroots organisation that she founded in 1977 to respond to the needs of rural Kenyan women and restore their degraded environment.

When we plant trees, we plant the seeds of peace and hope.

Wangarĩ Maathai

Maathai encouraged women to plant tree nurseries across the country, and they were given a small stipend for doing so. The Green Belt Movement has now planted over 51 million trees in Kenya.

In addition to this huge achievement in environmental conservation Maathai also became recognised for her strong commitment to human rights and democracy. She addressed the UN on a number of occasions and became a UN Messenger of Peace in 2009.

She was also became member of the Kenyan parliament in 2002 with an overwhelming 98% of the vote and was appointed Assistant Minister in the Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources.

She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004 for her "for her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace."

Quannah Chasinghorse

By now, almost everyone has heard of Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist. There are however many other young female environmentalists all over the world fighting the same fight, whose names are not so well known.

One of these is Quannah Chasinghorse, a 17-year-old Alaskan native hailing from the Han Gwich’in and Lakota Sioux Nations. As part of the Gwich’in Youth Council Chasinghorse has recently helped to secure protections for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which the Trump administration had opened to oil drilling.

This refuge, which constitutes a vast portion of the Alaska North Slope Region, is the largest national wildlife refuge in the US, and contains the greatest biodiversity of any protected area north of the Arctic Circle. It is home to a huge array of plant and animal species, including polar bears, eagles and caribou.

As someone who has grown up in this region and has strong cultural ties to the land, Chasinghorse is acutely aware of the effect climate change has had, and the way in which indigenous communities are disproportionally impacted by it.

The protection of the Porcupine caribou is especially important to the indigenous communities of this region. The Gwich’in people have depended on this species for thousands of years, and consider its survival to be entwined with their own.

The new Arctic Cultural and Coastal Plain Protection Act which she helped to bring about reinstates key safeguards that were stripped from the refuge in 2017 and will prevent oil drilling, protecting the precious biodiversity of the region.

Main image: Kenyan environmental and political activist Wangari Maathai was the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. © Wendy Stone/Corbis/Getty