In 2015 over 340 whales were involved in a mass-stranding event, beaching along the coastline of Patagonia, Chile.

As they were in such a remote location, the whales were not discovered for several weeks, by which time decomposition was severe and analysis difficult.

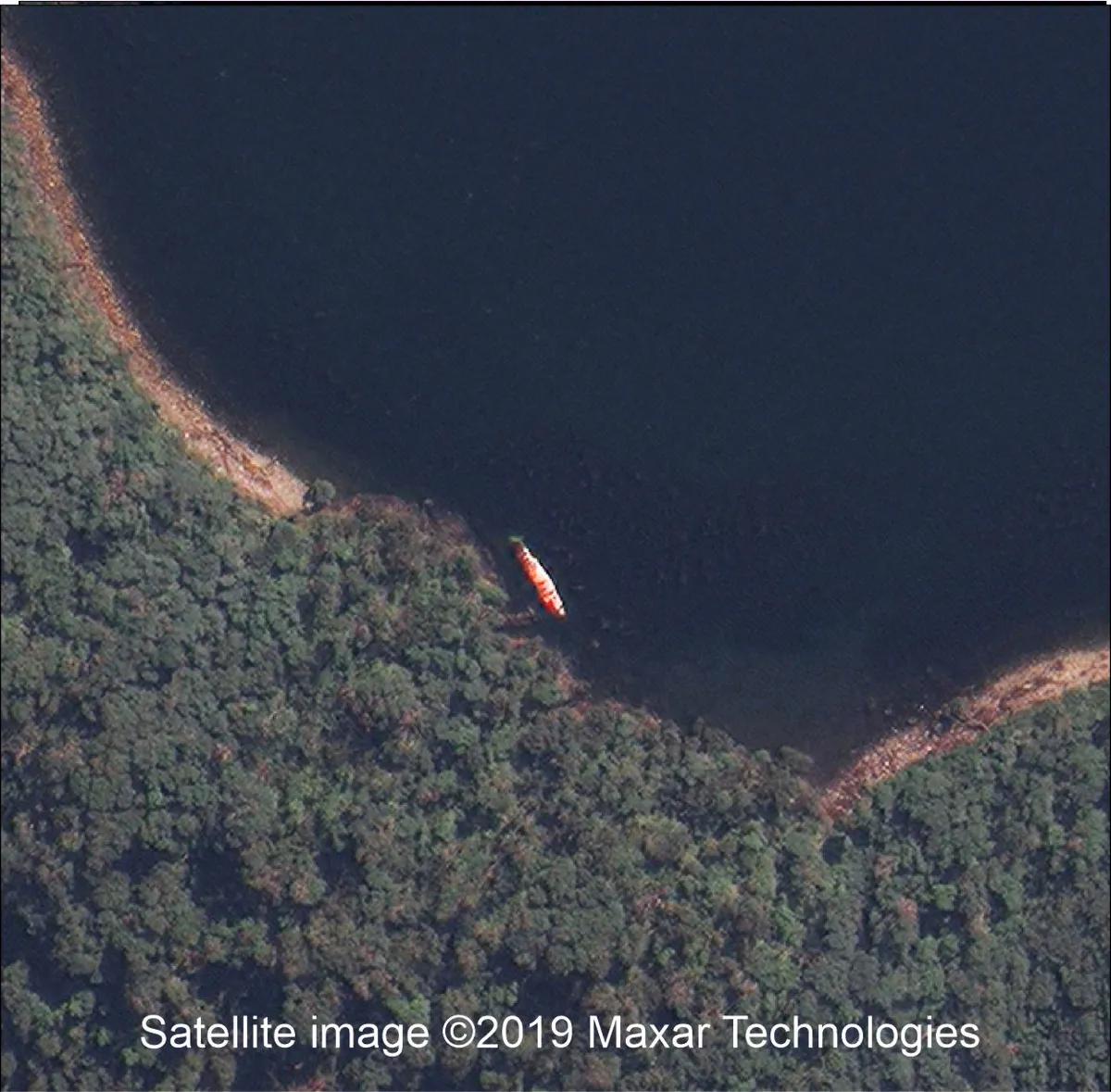

Scientists are now able to gain a better picture of what happened thanks to a new technique for analysing satellite images, known as Very High-Resolution satellite (VHR) imagery.

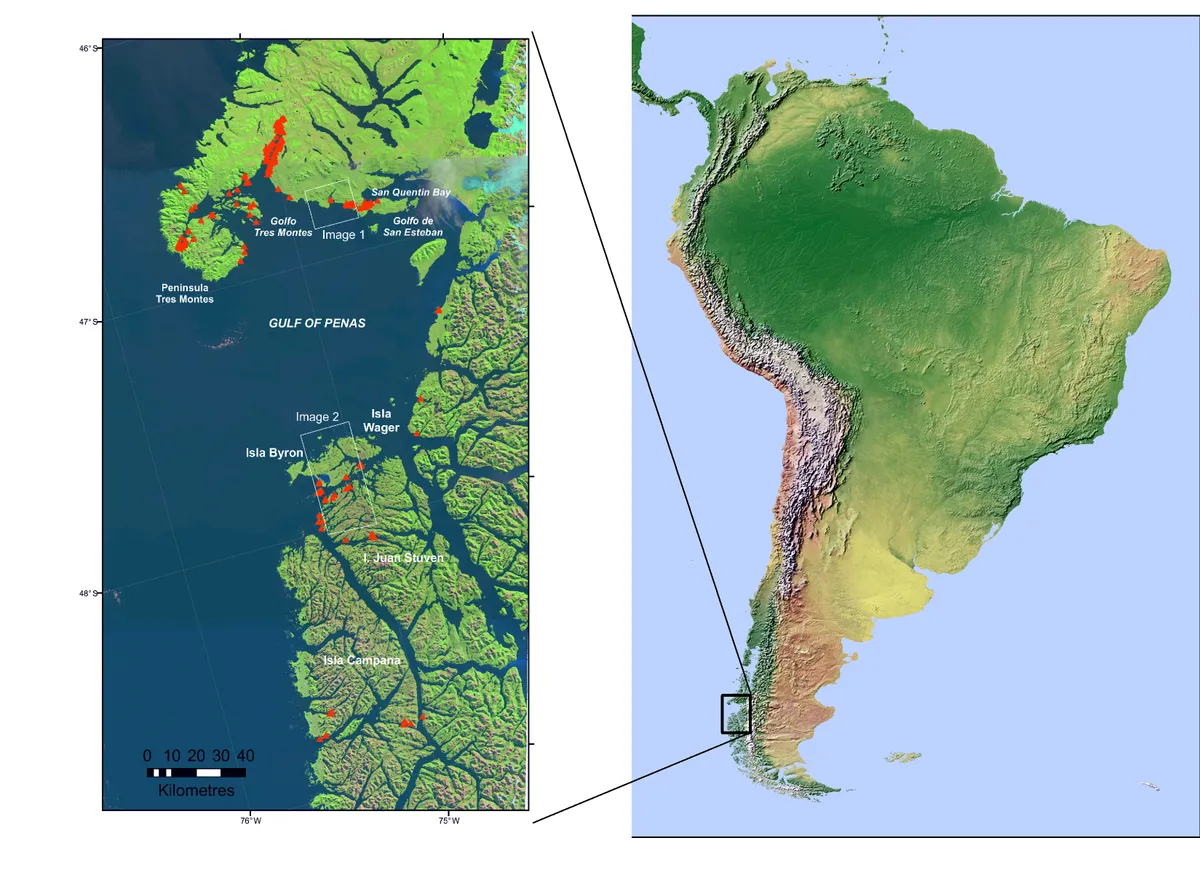

The researchers, hailing from the British Antarctic Survey and four Chilean research institutes, studied satellite images taken before the whales were discovered, thereby gaining an earlier insight into the extent of mortality and the conditions under which it occurred.

These images covered thousands of kilometres of the coastline, allowing the researchers to identify and count the dead whales, many of which had turned a recognisable pink and orange with decomposition.

The stranded animals were predominantly sei whales, a species of baleen whale which are endangered, mostly due to exploitation by modern whaling, but increasing. This mass die-off is a blow to their recovery, and the causes are still not understood.

In the past ‘red tides’ of toxic algae have been linked to marine mammal deaths in the region, so there is speculation that this could be a factor. The scale of death seen here is however unprecedented, and thus far unexplained. Going forward, this new technology may be able to spread some light.

“The causes of marine mammal strandings are poorly understood and therefore information gathered helps understand how these events may be influenced by overall health, diet, environmental pollution, regional oceanography, social structures and climate change,” says Dr Jennifer Jackson, a whale biologist at British Antarctic Survey.

“As this new technology develops, we hope it will become a useful tool for obtaining real-time information. This will allow local authorities to intervene earlier and possibly help with conservation efforts.”

This technology will be especially useful in remote and inaccessible regions, providing a crucial means to monitor the health of whales and their environment in a fast and cost-effective way. It is hoped that through this improved monitoring such devastating mass mortality might be avoided in the future.

Read the full paper at PLoS ONE.

Main image: Arial photograph of stranded whales. © British Antarctic Survey