A new study details the impact that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are having on marine mammals and reveals that UK harbour porpoises are unwittingly poisoning their own young, transferring the chemicals to them via lactation, as they detoxify their own bodies.

PCBs are a group of manmade chemicals, once widely used in electrical equipment, but discovered to be so toxic to humans and animals that production was banned internationally in 2001. They are however still lingering in ecosystems, with destructive effects.

The scientists, from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Brunel University London, analysed the PCBs present in 347 stranded harbour porpoises, and found that calves were carrying a more neurotoxic cocktail of these chemicals than their mothers were.

This is thought to be due to a process called maternal pollutant offloading, wherein the mother passively transfers contaminants to their young when fat stores are co-opted for yolk or milk production.

Rosie Williams, a researcher at ZSL and lead author of the study says, “It’s a tragic irony that juvenile porpoises are being exposed to a toxic cocktail of chemicals during feeding – when all they’re supposed to be getting are the vital nutrients they need for the crucial developmental stage of their life.”

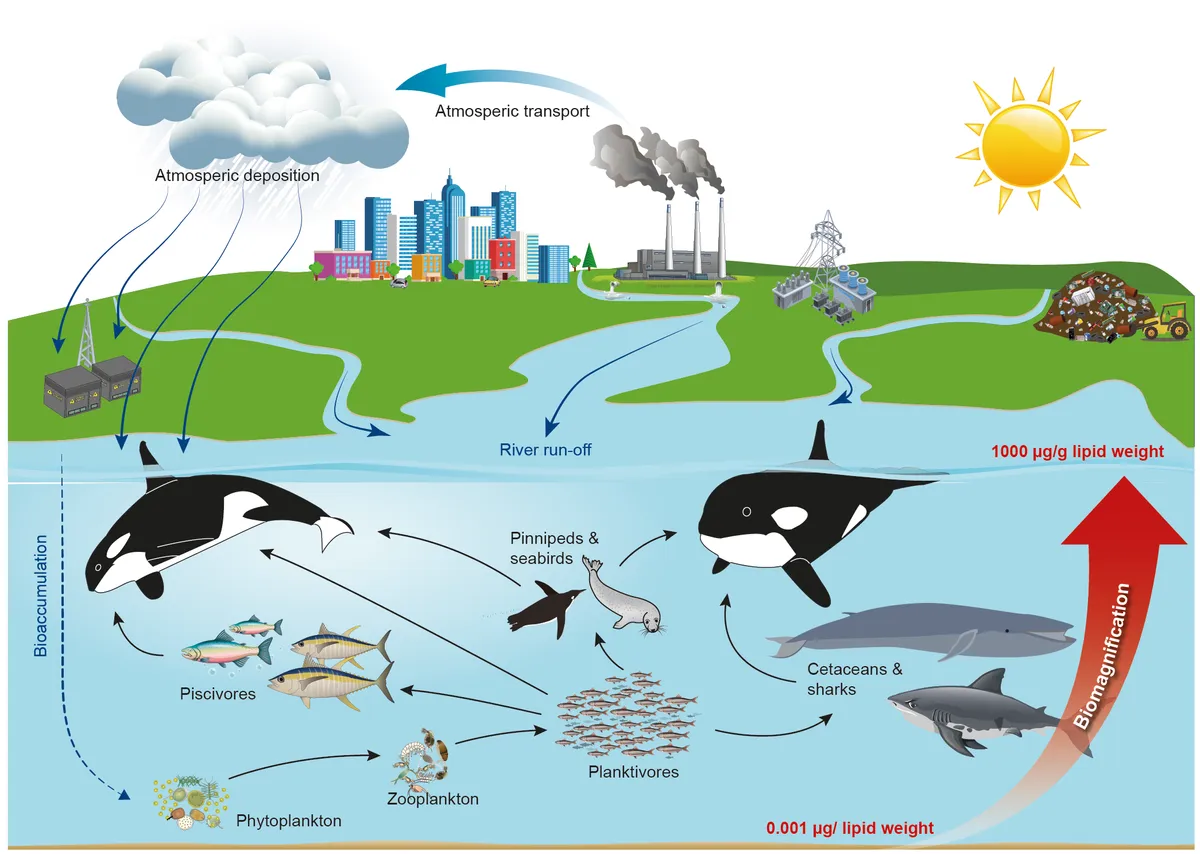

These pollutants are getting into the mothers in the first place through their food. PCB’s are a very persistent group of chemicals and are not easily broken down. This means that they can linger in ecosystems for a long time, and at different levels of the food chain.

Due to a phenomenon known as biomagnification, PCBs also tend to increase in concentration at they travel up the aquatic food chain, first consumed by tiny zooplankton, then small fish, then bigger fish and so on, until you reach large marine mammals.

Toothed wales, like porpoises and orca, are found with the highest concentrations of these toxic substances as they are high up in the food chain. This is known to cause suppression of their immune and reproductive systems.

“Our native population of orcas in the UK are facing extinction because of PCBs, with only eight remaining. As top predators, killer whales are exposed to some of the highest levels of PCBs, because there is an accumulative effect of PCBs as you go up the food chain," explains Williams.

Moreover, the results of this study demonstrate that despite the ban on PCB production, it is still finding its way into our precious marine ecosystems (through a process known as bioaccumulation).

This is thought to be partly via terrestrial run off. PCBs can cling to and persist in sediments for a long time, and can then be washed into waterways, or else evaporated into the air.

Dredging of underwater sediments can also release these chemicals into the aquatic environment. Whichever route they are taking its clear that the ramifications of these chemicals are still been felt nearly 20 years after the ban.

“It’s obvious that marine mammals are still experiencing the lingering impacts of PCBs, so identifying the sources and pathways that they are entering our oceans is a vital next step to preventing further pollution,” says Williams.

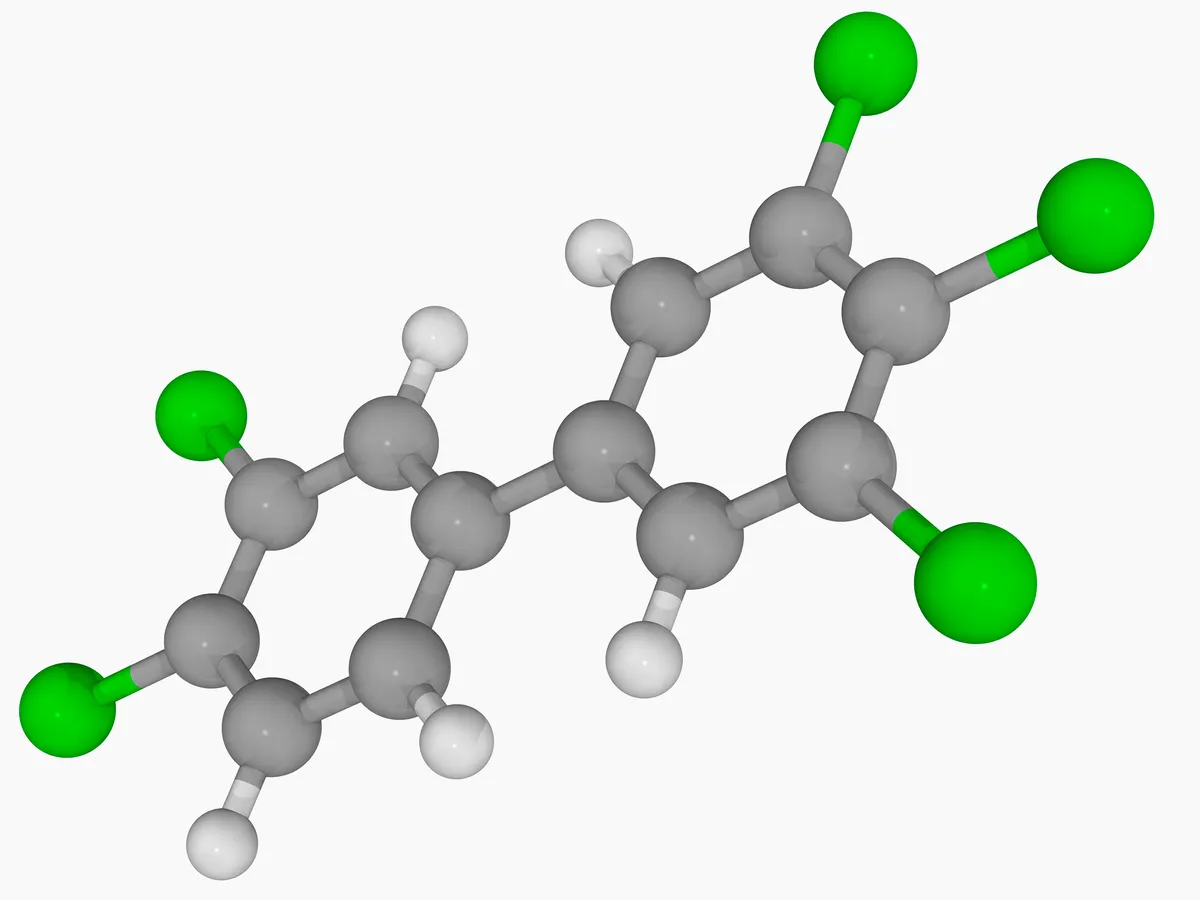

Another complication with PCBs is that they are not one uniform type of chemical, but a vast group with varying properties.

They have the same basic chemical structure, being made of carbon, hydrogen and chlorine atoms, but because these atoms can be combined in many different ways, a total of 209 different PCB molecules can be formed. Some of these more harmful than others. This makes it much harder to measure the impact of them on marine animals.

“Previously, scientists tended to monitor PCB concentrations by grouping them together and treating them as one chemical,” explains Williams. “But as we know, they’re a group of chemicals with different toxicity levels so it was a bit like trying to measure how much caffeine someone's had – without knowing whether they drank three cans of red bull or three cups of tea.”

“Our study has highlighted the need to change our approach to monitoring PCBs, to look at the composition of individual chemicals, so that we can get a better understanding of the risk posed by these chemicals to our marine wildlife.”

This study went some way in rectifying this by looking at the individual different PCBs present in the porpoise samples, and how they varied across age, sex and location.

They found that the 209 different PCB molecules have varied levels of persistence in marine mammals, with some types of the chemicals proving less toxic and more efficiently metabolised than others.

Co-author of the study Professor Susan Jobling, from Brunel University London's, Institute of Environment, Health and Societies says: “This research helps further our understanding of these legacy industrial chemical pollutants and the effects that different levels of exposure, in complex mixtures, may have.”

“Learning more about PCB exposure in juvenile animals is vital, so that we can try to mitigate the impact of these dangerous chemicals on populations and help protect the future status of marine mammals in UK waters.”

Francesca Bevan, chemical pollution specialist at the Marine Conservation Society said of the study,“This study highlights the impacts and devastating legacy of PCBs. Persistence, when it comes to any chemical, causes a huge problem as the chemical remains in the environment for very long periods of time without being broken down.”

“In the case of PCBs, although many of the chemicals’ uses were banned many years ago, PCBs persistence has meant that we’re only now feeling the true impact in the environment. Unfortunately, other persistent chemicals, perhaps with similarly long lasting impacts on our environment and wildlife, are still being used; we need to see such chemicals restricted and removed from use as soon as possible.”

Read the full paper in Science of the Total Environment.

Main image:Harbour porpoise ready for postmortem at ZSL. © CSIP-ZSL