For the first time ever, a European eel has been recorded setting off on its epic migration journey as it left the shelter of the Slimbridge wetland reserve.

The footage was captured by an acoustic camera which creates images out of sound.

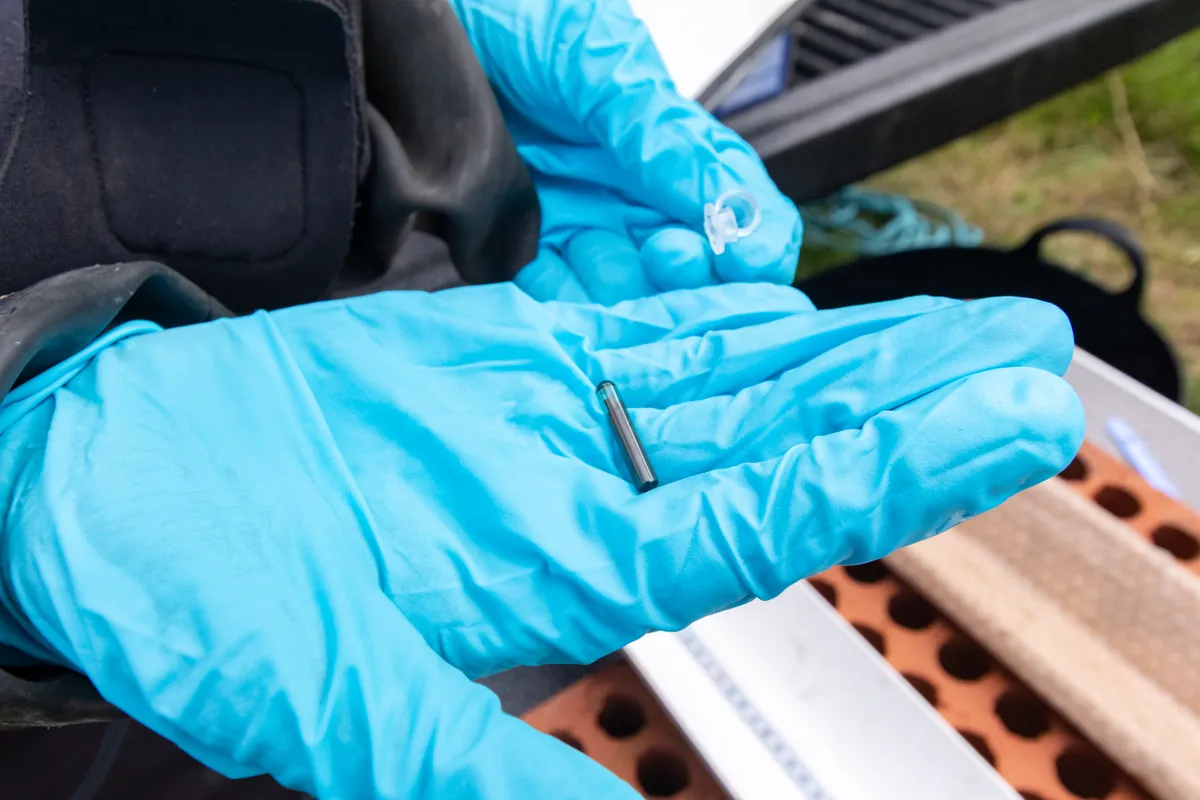

In recent years scientists have been monitoring the activities of the eels that live out their lives here before they begin their own great migration. In 2018 conservationists from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) began microchipping these eels, with the aim of better understanding their actions.

These microchips work in the same way as those pet-owners use and enable the researchers to identify each individual eel.

Every autumn Britain’s eels undertake a truly mammoth journey, travelling from the freshwater wetlands of the UK, across the Atlantic Ocean, and to the Sargasso Sea in the Carribean – a distance of more than 3000 miles.

The eels must complete this migration in order to breed, and thus complete the final chapter in their curious life history.

The life cycle of the European eel is one that has long puzzled scientists and fishermen alike. This is partly because they never captured anything they could identify as a young eel. This may also be why the Greek philosopher Aristotle decided that they sprang up spontaneously from the mud.

It was eventually discovered that this was because eels do not spawn in our waterways, but instead head out to sea to breed. The larvae will then drift back towards their parents’ former homes in Europe in a migration that takes about 2 years. As they approach the European coasts they metamorphosis into a transparent stage, and are known as glass eels.

About 100 million of these young eels end up in the Severn Vale – the large river system that drains into the mighty Severn Estuary. The Seven is a key outpost of the species, and the most northerly place where they are seen in 'superabundance'.

In the summer of 2019 a total of 6 mature female eels were tagged at Slimbridge, and because of a remote microchip reader installed by the sluice opening of the reserve, the researchers were able to record them as they left to head out to sea. This confirmation that they could successfully begin their route was encouraging for the scientists.

“Once eels mature in the freshwater wetlands off the Seven Estuary they must be able to swim back to the Sargasso Sea and breed to complete their life cycle - so it’s fantastic to know that the eels can navigate their way back out of our wetlands,” says Emma Hutchins, WWT’s Head of Reserves Management.

The reason that this seemingly small victory is being celebrated, and that conservationists are focusing on this species in the first place, is that European eels are Critically Endangered and in severe decline.

The number of European eels across the continent have dropped by as much as 95% in the past 25 years. This severe drop in population is in part due to the loss of wetland habitats such as that found in the Severn Vale, as well as the destructive impacts of man-made barricades which halt their journeys and hydropower turbines that chop them to pieces. Humans have effectively barricaded the rivers and there are now over 1 million barriers to eel migration.

“Worldwide, eel numbers have plunged dramatically in recent years as much of their wetland habitats have been destroyed or degraded and access into these wetlands has been reduced or prevented by man-made structures such as pumps and weirs,” explains Hutchins.

Another great threat to this species is the illegal trade in glass eels. It is estimated by The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (EUROPOL) that up to 350 million glass eels are illegally trafficked to Asia every year, where they are considered a culinary delicacy.

This is one quarter of the annual glass eel recruitment (the number of baby eel that arrive on European waters each year) and is known as one of the largest wildlife crimes in the world and certainly the largest emanating from Europe, as it is worth about 3 billion euros.

There is cause for hope however. Europe gradually began to wake up to the perilous situation that humankind had forced upon our eels, in part thanks to the dedicated action of such groups as The Sustainable Eel Group (SEG), who champion the cause of this fish by advocating for migration-friendly waterways and against the illegal trade. As a consequence of the unblocking of migratory pathways, with new eel passes and modified pumps, eel numbers are on the rise.

The illegal trade is also now being curbed, thanks in part to the listing of the European eel in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

This year 154 traffickers were arrested, and many gangs broken up over their involvement in the glass eel trade. So far prison sentences are being passed in France and Spain.

According to Andrew Kerr from the SEG, “2019 was the year the tables were turned on traffickers. The volume of trafficked fish should now drop dramatically.”

Main image: European eel in reeds. Warwickshire, UK. © Mike Lane/Getty