A unique 2m-long trackway of dinosaur footprints set in rock outside the town of Glenrock in Wyoming, USA has provided insights into the speed of one of the world's deadliest prehistoric predators, the tyrannosaurus rex.

- What were the fastest dinosaurs – and just how fast were they? Meet the prehistoric speed machines

- How powerful was the bite of a T.rex?

Could you have outrun tyrannosaurus rex?

“Having a trail of tracks is important,” says paleontologist Scott Persons of the University of Alberta in Canada..“With it, you can calculate an estimate of how fast the tyrannosaur was walking.”

In papers published in the journals Cretaceous Research and Scientific Reports, Persons describes the footprints and how they were used to calculate the dinosaur’s height and stride, and therefore its speed at the time they were impressed into the soft mud at the side of an ancient ocean, long since dried up.

As the first footprint clearly shows an animal with three forward-pointing toes and one smaller one facing backwards, it was possible to identify what made the imprint as a meat-eating dinosaur.

The only meat-eaters known to have existed in the area at the time were tyrannosaurs.

“Based on the age and size of the footprints, the trackmaker can be identified as either a sub-adult Tyrannosaurus rex or a Nanotyrannus lancensis,” writes the authors in the paper’s summary.

The length of the footprint also gave Person’s team an estimate of the height of the tyrannosaur’s hips from the ground.

The relationship between speed and leg length is a general anatomical rule observable today in living animals.

For example, cheetahs are faster and have proportionately longer legs than lions, which are faster and have proportionately longer legs than hyenas.

This measurement, coupled with the distance between the steps and equations devised by observation of the motion of a range of existing bipeds, led the researchers to the conclusion that the dinosaur’s walking pace would probably have been between around three to five miles an hour, so easily outpaced by even an unfit jogger.

“The trackway offers a record of a tyrannosaurid pace length, which permits the speed of the trackmaker to be calculated at 4.5–8.0 km/h,” writes lead author Persons.

“This result discounts previous speculation that tyrannosaurid walking speeds were notably slower than those of other large theropods.”

“How fast a predator can run is obviously important,” he says.

“Speed determines what prey you can catch, how you hunt it, and the sort of environment that you are most successful in.

“That’s true for modern carnivores, and must have been true for dinosaurs.”

“Over evolution, you have these two conflicting forces: the need for speed and the need for weight support.

“You cannot just compare little dinosaurs to big dinosaurs; you have to factor out the influence of body mass.”

So what if a tyrannosaurus rex was coming at you at full tilt, then?

Other single footprint studies have already estimated a potential top speed of around seven miles an hour.

So you’d have needed to be a reasonably accomplished runner, but nowhere near a Usain Bolt.

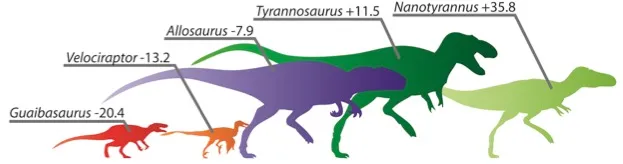

Calculated speed adaptation scores for various dinosaurs. From left to right, Guaibasaurus was an early dinosaur with a low score typical of primitive forms; despite its pop culture status, Velociraptor is revealed to be among the least swift of the carnivorous dinosaurs; the Jurassic predator Allosaurus was large and moderately adapted for speed; despite its bulk, Tyrannosaurus scores high on the speed charts; the controversial species Nanotyrannus was the bipedal dino best adapted for speed.