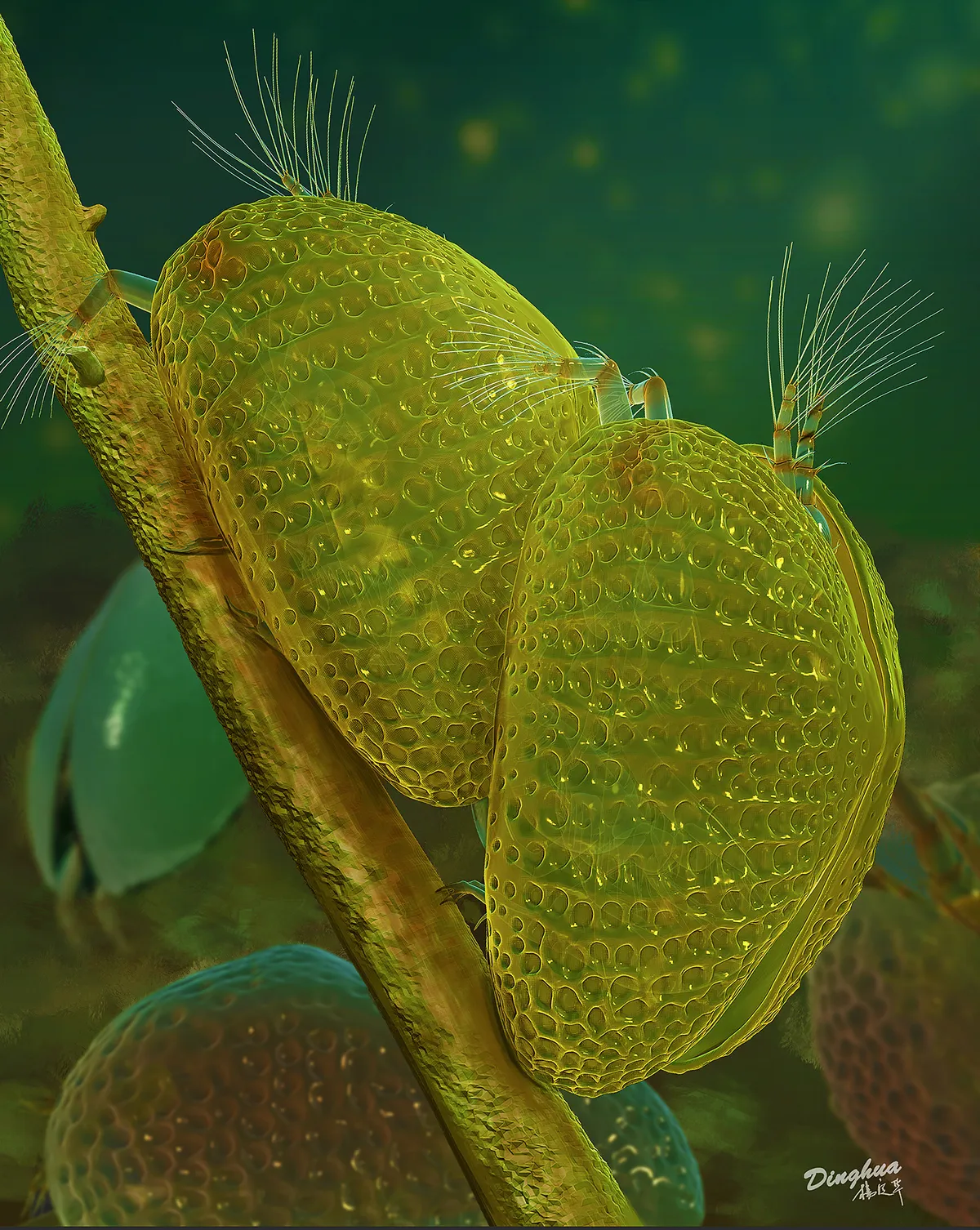

100 million years ago during the Cretaceous period, in what is now Myanmar, ostracods living in a coastal lagoon, fringed by trees, had just had a sexual encounter when they became trapped inside the resin of a tree.

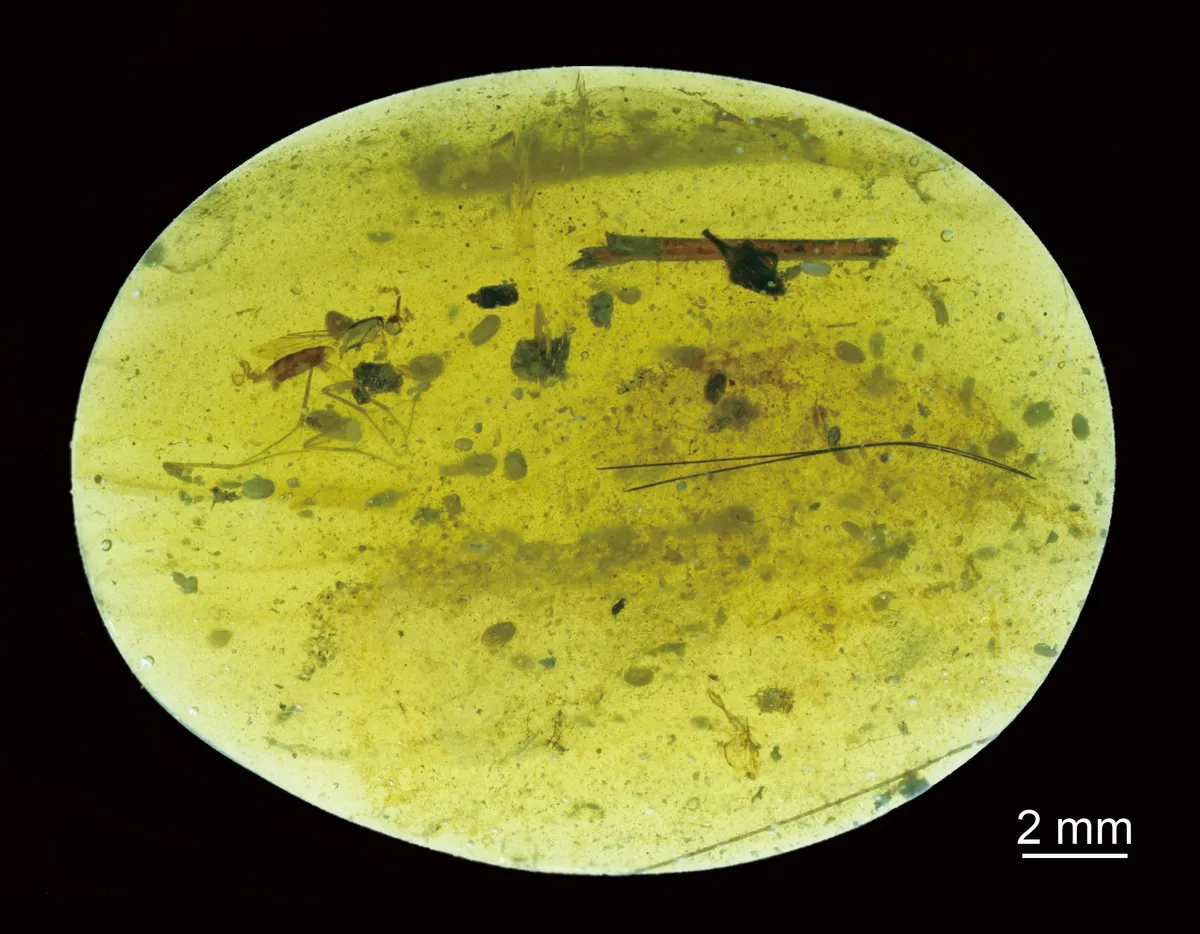

Cocooned for millennia, encased in a coffin of amber, the microscopic crustaceans remained preserved in a time-capsule.

But small though they may be, their recent discovery is a big deal in the science world, and has been hailed as a ‘spectacular find’ by scientists, as fossilised sperm are extremely rare — none previously discovered have been anywhere near as old as this. By comparison, the oldest known examples prior to this were a mere 17 million years old.

The international study involved researchers from Queen Mary University of London and the Chinese Academy of Science. Their findings on the new, ancient, crustacean species, named Myanmarcypris hui, were published in Royal Society Proceedings B.

Although finding fossil shells is not unusual, specimens that have been preserved so perfectly in ancient amber is very rare indeed.

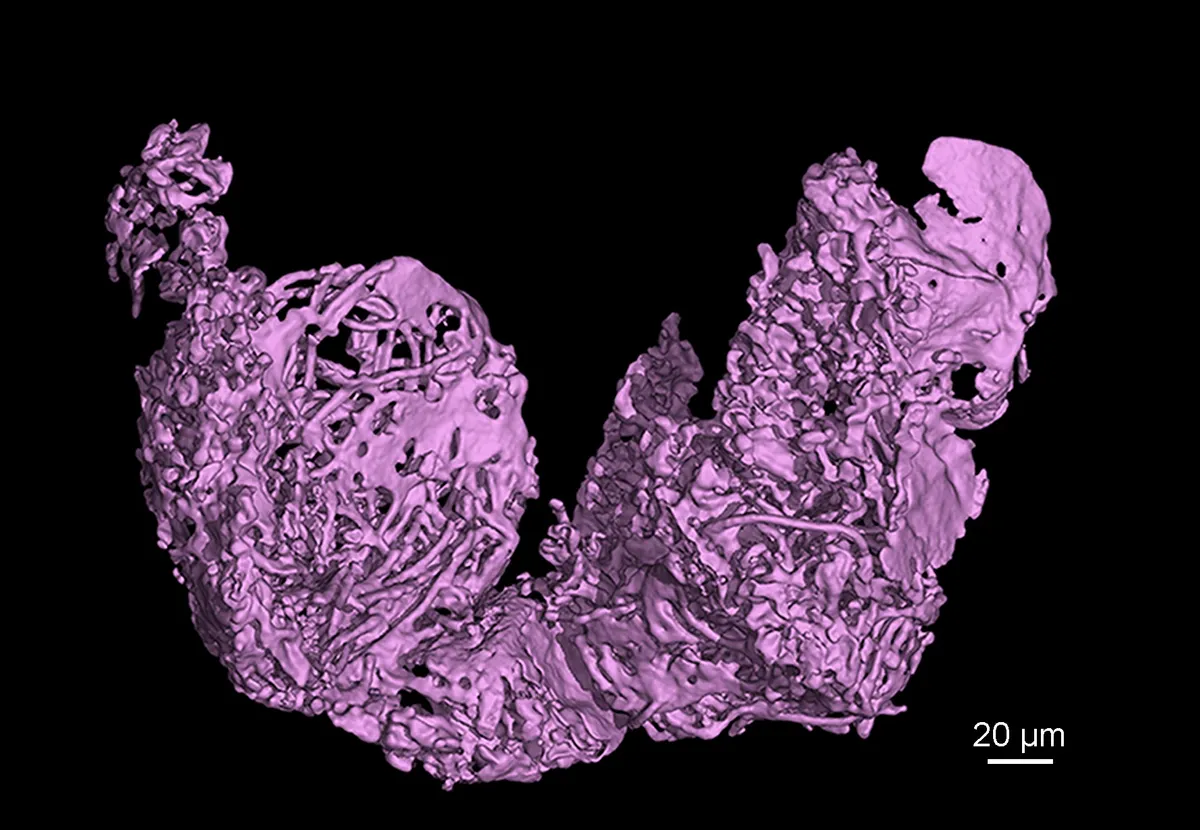

Using x-ray microscopy and computer-aided 3D reconstructions of the ostracods embedded in the amber, the team were able to reveal incredible detail, and they were astonished by what they found.

“The results were amazing,” said Dr He Wang of the Chinese Academy of Science in Nanjing, who led the study. “Not only did we find their tiny appendages to be preserved inside their shells, we could also see their reproductive organs.

“But when we identified the sperm inside the female, and knowing the age of the amber, it was one of those special ‘eureka’ moments in a researcher’s life.”

Although both male and female ostracods were found inside the ancient amber, the sperm was found in the female specimen, indicating a sexual encounter had just taken place shortly before the creatures were encased in their amber tomb.

“Analyses of fossil ostracod shells are hugely informative about past environments and climates, as well as shedding light on evolutionary puzzles, but exceptional occurrences of fossilised soft parts like this result in remarkable advances in our understanding,” said Dave Horne, professor of micropalaeontology at Queen Mary University of London.

Learn more about fossilised discoveries:

Ostracods as a species (also sometimes known as ‘seed shrimp’) have survived for more than 500 million years and live in a diverse range of aquatic environments, from deep oceans, to freshwater lakes and rivers.

The tiny crustaceans are less than a millimetre long and the males boast two penises. Although most other animal species opt for quantity over quality when it comes to sperm, producing tens of millions of minute sperm, ostracods (along with fruit flies) produce relatively small numbers of ‘giant’ sperm.

These sperm are many times longer than the animal itself, and exist coiled up inside the tiny crustaceans.

Finding giant sperm that is 100 million years old reveals the important discovery that even at this exceptionally early period in history, giant sperm had already evolved in ostracods, demonstrating that this must have been a highly successful reproductive strategy to have survived for so long.

“Sexual reproduction with giant sperm must be very advantageous,” said the paper’s co-author Dr Renate Matzke-Karasz of Ludwig Maximillians University in Munich.

“To show that using giant sperms in reproduction is not an extinction-doomed extravagance of evolution, but a serious long-term advantage for the survival of a species, we need to know when they first appeared.”

Main image: Only a few of the ostracods in the amber piece could be studied using light microscopy, like this individual of the new species Myanmarcypris hui. Its antennae extend from the bivalved shell. Most other specimens lie too deep in the amber or the view is obstructed by debris particles. © He Wang and Xiangdong Zhao