If you've ever visited a city farm, you'll understand just how important these places are. City farms provide vital green spaces and wildlife havens in the concrete sprawl of towns and cities, and offer people the chance to regularly connect with nature. It's been 50 years since the first city farm was established in Camden, London, and their role as havens for wildlife and biodiversity has been growing ever since.

What is a city farm?

City farms are places where you can get a taste of rural life without leaving that city. They're often set up and run by community initiatives within urban areas. There are 50 city farms in the UK.

• Ten of the best city farms to visit in the UK

What was the first city farm in the UK?

Kentish Town was the first to open its doors, in October 1972. Only 5km as the crow flies from central London, it’s squeezed between two railway lines and dense rows of housing in Camden.

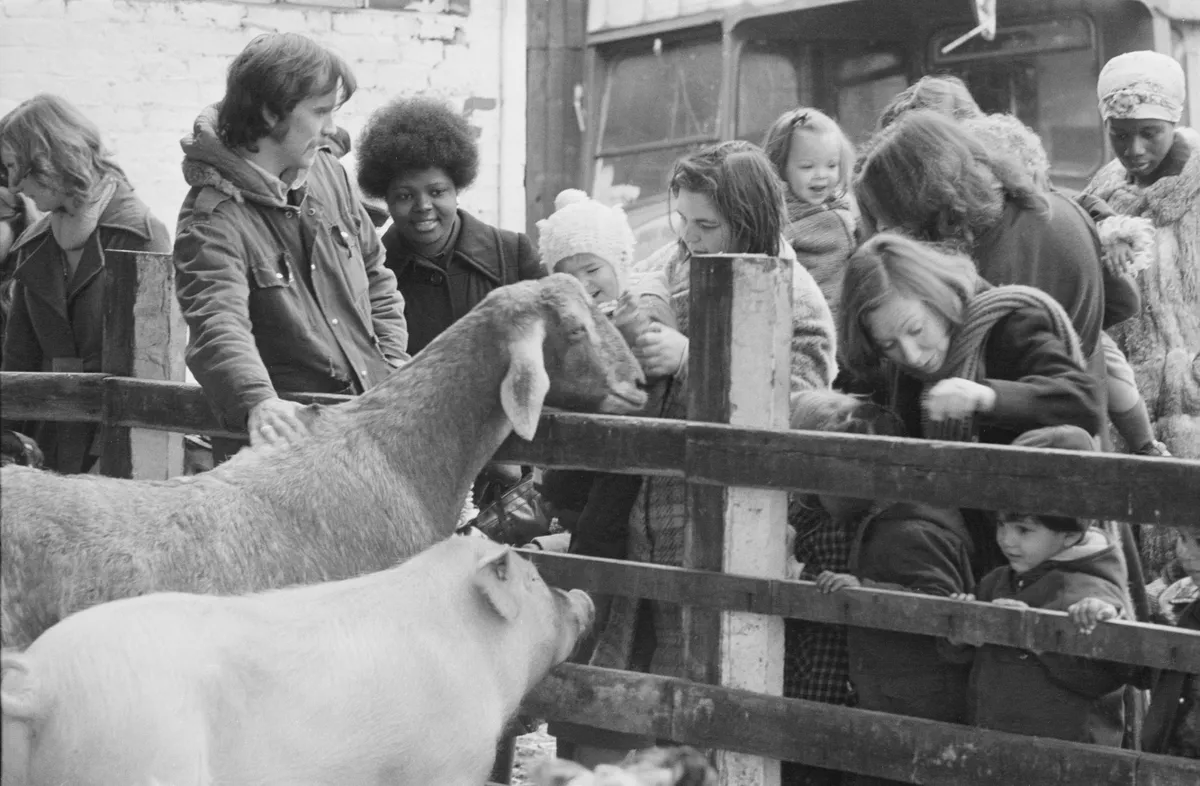

The original idea of a city farm was a simple one: take a small piece of land and use food production and farming as a way to connect communities. Following the founding of Kentish Town, city farms started to pop up all over the UK. Green oases in landscapes of tarmac, concrete and steel, city farms became places where children who might rarely visit the countryside could see a cow close-up, collect eggs from the hens and connect with nature.

What is the biggest farm in London?

The UK’s largest city farm is Woodlands Farm in Greenwich, at 89 acres. Most other city farms are much smaller, yet they all play a key role in reversing some of the species and habitat loss that we’re seeing. All urban green spaces matter for wildlife, but city farms offer that bit extra in terms of the habitats they can squeeze into a space not much larger than a football pitch.

“City farms can be hugely important for urban wildlife,” says ecologist Peter Brash. “The mix of habitats and the grazing animals can provide something missing from other green spaces, such as parks.”

Amy Coulthard, director for nature recovery at Avon Wildlife Trust, agrees. “City Farms provide vital green infrastructure in towns and cities, acting as homes for nature and places that can inspire people to connect with wildlife.”

Traditional mixed farms, which raise livestock and grow crops, were once a common sight in the countryside, but the decline of the smaller farm has seen a decrease in number. Mixed farms bring great benefits to wildlife and have been replicated in city farms. Lightly grazed meadows burst with wildflowers such as oxeye daisy and cuckooflower in summer; orchards are homes to mistle thrushes, lesser-spotted woodpeckers and bats; while farm buildings provide nesting sites for swifts and blue tits.

Bath City Farm, a 37-acre wildlife haven, is a wonderful example of why these places matter for wildlife in urban landscapes. Set up in the 1990s, the farm is visible from the famous Royal Crescent. Most visitors spend their time getting to know the goats and Shetland ponies, but surveys reveal why the farmland is so important for wild animals.

Photographer and ecologist Mike Williams has been recording the species at the farm for five years. “For me, it’s the abundance of species found at city farms, rather than the potential for rarer wildlife, that’s really important. In cities, these places might offer the only decent patch of green space for miles. They can act as reservoirs for many species.”

Mike’s list currently exceeds 700, and includes 21 species of butterfly (ringlets and the Essex skipper among them) and 17 types of fungi (including King Alfred’s cakes and veiled oyster). New species turn up every year. A red kite was recorded for the first time in 2021, while the alder leaf beetle and Roesel’s bush crickets have become relatively common sights on the grassland.

Increasingly, the work of city farms is moving beyond the confines of a small patch nestled in the urban sprawl. Swansea Community Farm (the only city farm in Wales) is not only nurturing farm animals, wildlife areas and allotments, but is also at the heart of a local partnership to improve a rare urban heathland known as Cadle Heath. Donkeys and goats have been loaned out to graze the space into an environment suitable for plants such as devil’s-bit scabious (which attracts the scabious mining bee) and birds, including goldcrests and skylarks.

“Our volunteers have driven our increased focus on conservation work,” says wellbeing officer Katharine Aylett. “After some basic training from Buglife, they’re now more involved in regular wildlife survey work. These new skills have boosted their confidence and created positive connections with the natural world.”

Ecologist Peter seconds the approach of working with partner organisations to help wildlife flourish in cities. “It’s about thinking beyond the boundary,” he says. “We need to consolidate the links from farms to other green and brownfield sites, both within and outside the city.”

Conservation in the capital

For the team at Mudchute City Farm, nestled under the gaze of London’s Canary Wharf, working with partners such as Tower Habitats and Froglife makes total sense.

“Six of our native-breed sheep have been helping to graze an area of Green Park, right by Buckingham Palace,” says farm manager Tom Davis. “Now, when you walk through there in summer, it’s humming with insects. It’s helping to raise awareness of what the farm does while also improving biodiversity in the heart of the capital.”

Mudchute has ambitious plans for the wildlife on the 32 acres it manages. It’s one of the Rare Breed Survival Trust’s approved conservation centres and these animals are key to improving areas of parkland and woodland. “Their teeth, hooves and poo will enhance the richness of our farm,” says Tom. “Take some of the willow and hazel coppice – grazing here will open up the area and we’ll see snowdrops and celandines again.”

For Amy, it’s about how city farms can fit into the bigger picture. “There’s a really interesting role that city farms can play as conveners of change to help tackle the ecological emergency,” she says. “This could be as a wild hub where local authorities and wildlife organisations can collaborate to reverse some of the species declines that we’ve seen over the past 30 years, with hedgehogs or house sparrows, for instance.”

In what feels like a pivotal new chapter for city farms, they’re also helping to deepen our connection with nature. This includes supporting volunteers who might be overcoming personal challenges, or visitors for whom a trip to a city farm might be their only experience of a green space. Visitors, like Mike, for example.

Mike’s world was turned upside-down when he was diagnosed with ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis). He went from being a busy ecological consultant, travelling around the UK, to being unable to leave his home. “To find myself in a position where I could barely get out of the door was soul-crushing,” he recalls. “But having Bath City Farm nearby was amazing. I had easy access to green space and could keep up my natural history skills at my own pace – and rekindle my passion for wildlife photography.”

Connecting with nature

Swansea Community Farm has seen first-hand the impact being close to nature has on volunteers. One of them has discovered a passion for bees and now spends hours collecting data. “Many volunteers had little experience of conservation work before coming to the farm,” says Katharine. “But they all quickly recognise the benefits for their wellbeing.”

For Miles Richardson, a professor at the University of Derby who has been researching the importance of our connectedness to nature, city farms can also help people notice nature more. “It’s clear that we have a fundamental and basic need to connect with nature. Yet we’re losing the ability to notice wildlife in our daily lives. For many people living in cities, spending time in green, natural spaces is the exception rather than the norm. That’s why city farms really do matter; they provide places where wildlife can flourish and spaces where volunteers and visitors can have that regular connection with birdsong, butterflies or wildflowers.”

Amy sees another role for city farms – inspiring visitors to think about the relationship between the food they eat and the natural world. “For 50 years, city farms have played a huge role in bringing to life the story of how our food is produced,” she says. “The movement deserves greater recognition for its role in tackling the crisis facing the natural world.”

These much-loved places, which welcome over a million visitors a year, are now on the frontline of efforts to tackle the ecological emergency. Combined, all city farms would cover an area roughly equal to one large farm in the countryside. Yet, collectively, their impact far outweighs their size, by offering habitats that can be at the heart of a movement to rewild our cities and bringing more nature into the lives of the millions of people that live in them.

Main image: A sheep grazes at Mudchute City Farm © Daniel Leal/Getty