For as long as humans have existed, we’ve shared our world with cats. Some we’ve welcomed into our homes, others we’ve kept at arm’s length for fear of becoming dinner, says Will Newton.

- What’s the world’s largest cat?

- What’s the world's smallest cat? Meet the tiny felines barely bigger than a ruler

- The world's rarest cats, from the endangered snow leopard to the uber-cute Iriomote cat, on the brink of extinction

When did cats first appear?

Cats marked their territory long before we did, emerging in Eurasia 30 million years ago (Mya) and 25 million years before our ancestors first appeared in Africa. In the time since, they’ve explored five of the seven continents and established themselves as apex predators in a range of habitats, from tropical rainforests to mountain ranges.

As a group, cats - or Felidae - are known for their retractable claws, prominent canines, striking fur patterns, and powerful, slender bodies. These characteristics are what makes cats ‘cats’, and they’re shared by all of today’s 41 extant species and their roughly 120 extinct relatives.

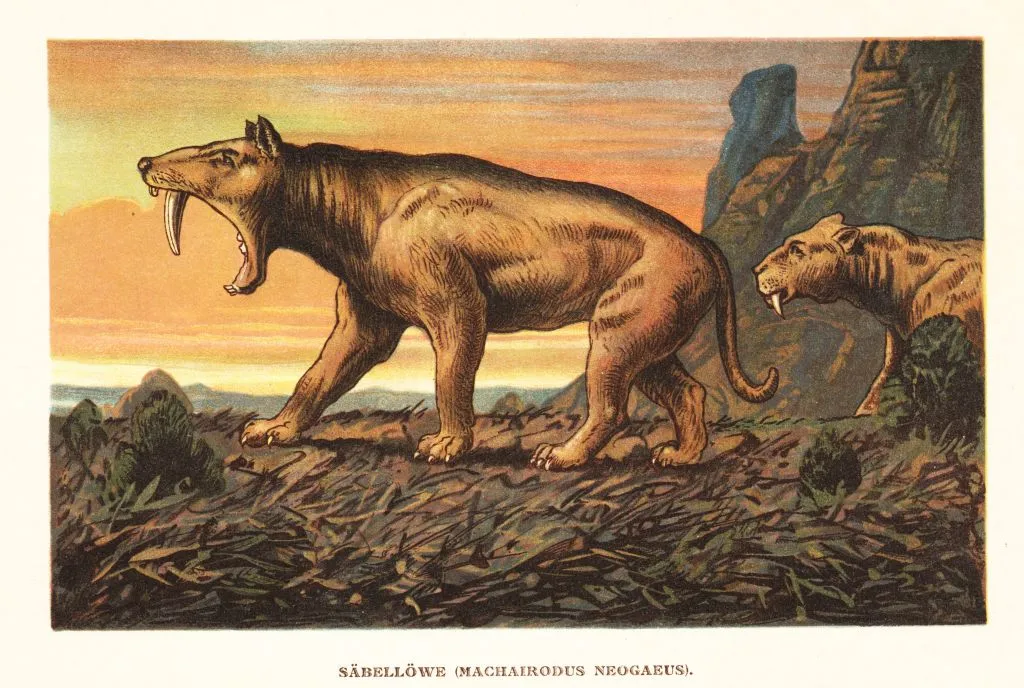

Top 10 prehistoric cats

A lot of prehistoric cats took these characteristics to the extreme, evolving into stealthy assassins capable of killing giants such as mammoths.

Proailurus - The First Cat

Not much larger than today’s house cats, weighing in at just 9kg, Proailurus is widely considered the first ‘true’ cat and a common ancestor of all extant felines.

It first appeared in Eurasia ~30 Mya, during a time when the continent’s grasslands were expanding and its tropical forests were receding. Its fossilised remains have been found in Spain and Mongolia, suggesting it had a very large range.

Proailurus was built like a cougar, with a long tail, large eyes, and sharp claws and teeth. It’s thought to have been at least partially arboreal, hunting on forest floors before dragging its prey up into the safety of the canopy, much like modern leopards. Its prey likely consisted of small, deer-like creatures and early rodents.

Smilodon - The Sabre Tooth Cat

This infamous predator hunted on the same frost-covered, American grasslands as our Ice Age ancestors, competing with them for mammoth, mastodon, and bison carcasses up until 10,000 years ago.

Smilodon was more robustly built than any living cat, looking more like a bear with its stout hind limbs and long, powerful forelimbs. This stocky frame, plus the 28cm-long, protruding canines that give it its name, made it a specialist hunter built to ambush large prey rather than run it down, like today’s big cats do.

Known from hundreds of fossils pulled from La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, US, Smilodon is perhaps the most studied prehistoric cat. These natural traps claimed the lives of thousands of animals during the Ice Age, including Smilodon, but thankfully preserved their bones for us to study.

Cave Lion - The UK’s Last Big Cat

Today’s big cats are largely confined to declining habitats in Africa, Asia, and South America, but during the Ice Age their close relatives, cave lions, roamed across Europe, making their way as far north as the UK.

- Britain's lost beasts: when did the moose, wolf and bear go extinct in UK?

Many prehistoric animals – especially dinosaurs – were absolutely enormous. A scientist explains why they were so darn big

These lions (Panthera spelaea) looked a lot like modern lions (Panthera leo) and are estimated to have diverged as recently as 500,000 years ago.

Cave Lions preyed on a variety of large mammals, from reindeers to bear cubs. They’d seek out caves on their hunt for the latter and, in doing so, bump into our ancestors as they sought shelter from the elements.

Our interactions with these big cats have been documented in several stunning cave paintings found in France. A number of ivory carvings and clay figurines depicting cave lions have also been found at sites across Europe.

Homotherium - The Scimitar Tooth Cat

Closely related to the sabre tooth cat, Homotherium was part of a subfamily of big cats that, despite having no living descendants, was incredibly successful and widespread, with nearly 70 species spread across five continents. Homotherium was arguably the most successful member of this subfamily, ranging from Africa to North America for a period of roughly four million years.

In comparison to its close cousin Smilodon, the canines of Homotherium were noticeably shorter (~10cm) and, interestingly, serrated. It also had longer hind limbs than Smilodon, making it more suited to running down prey.

These adaptations, combined with genomic studies that have shown Homotherium was highly social, have led researchers to suggest they hunted in packs.

At a cave in Texas, several Homotherium were found amongst the remains of 400 juvenile mammoths, leaving no questions as to what they preyed on.

Simbakubwa - The Great Lion

While its name in Swahili may translate to ‘great lion’, this huge predator was not a big cat, but rather a hyaenodon - a group that diverged from a shared ancestor millions of years before cats became ‘cats’.

It lived ~23 Mya in Africa and looked like a tiger, though it was significantly larger and, according to estimates, would have weighed in at 1,300kg - roughly 900kg heavier than the largest tiger ever recorded.

Simbakubwa, unlike other prehistoric animals, wasn’t found in the field. Instead, it was discovered in a long-neglected museum drawer by a student. The fossils found were several jaw bones complete with some vicious-looking, self-sharpening teeth scientists say were designed to slice effortlessly through the tough meat of its prey - likely rhinoceroses and early elephants.

Miracinonyx - The American Cheetah

This big cat looked like a cross between a cheetah and a cougar, and while it may be more closely related to the latter, it’s thought that it lived more like the former, hunting small, swift herbivores like mountain goats and pronghorns across grassy plains.

- The extinct, mighty prehistoric Acinonyx pleistocaenicus was the largest cheetah ever, weighing up to three times more than modern cheetahs

- What's the difference between a cheetah and a leopard?

Miracinonyx lived in North America from ~2.5 Mya to 16,000 years ago. It stood 85cm tall, weighed in at 70kg, and had a body length of more than 2.5m. It wasn’t quite as fast as a modern cheetah, but its body was still built for speed.

Its natural prey, pronghorns, still live in North America and continue to exhibit adaptations that some scientists believe they evolved to outrun Miracinonyx, such as their large lungs, light bones, and cushioned, shock-absorbing toes.

Dinictis - The False Cat

Part of a group known as “false sabre tooth cats”, Dinictis wasn’t a ‘true’ cat and lived a few million years before the first cat, Proailurus. Dinictis was a nimravid and thus closely related to cats but, crucially, part of its own distinct family.

It looked quite similar to a modern leopard, with its low-slung, slender body, but it had noticeably shorter legs and feet. It’s believed Dinictis walked flat footed, rather than on its toes like cats do.

Dinictis lived in North America from the Late Eocene to the Early Miocene (~37-20 Mya), hunting small, deer-like creatures in scrub and open woodlands. As its habitat disappeared and was replaced by grasslands in the Miocene, it may have been forced to compete with several early cats, which were better adapted to savanna-style living.

Xenosmilus - The Shark Tooth Cat

Of the roughly 70 species of sabre tooth cats, Xenosmilus was perhaps the most extraordinary. It had short, robust hindlimbs like Smilodon, and mildly elongated, serrated canines like Homotherium. The rest of its teeth were also serrated and arranged in a pattern that gave it a bite less like a cat’s and more like a shark’s. This allowed Xenosmilus to fully interlock its teeth and cut straight through prey when biting down.

Some scientists have theorised that Xenosmilus may have hunted using a ‘bite and retreat’ strategy, inflicting devastating wounds before stepping back to let its prey bleed out.

Just like its cousins Smilodon and Homotherium, Xenosmilus hunted small to large-sized herbivores that used to roam the grasslands of North America. It also lived at a similar time, from ~2 Mya to 300,000 years ago.

Pseudaelurus - The Intrepid Explorer

Some 10 million years after the first cat, Proailurus, established a foothold in Eurasia, its successor, Pseudaelurus, wandered into North America and ended a period in the fossil record known as the “Cat Gap” - a seven-million-year-long period (~25-18 Mya) when cats and cat-like animals seemingly ‘disappeared’ from the continent.

Pseudaelurus, a lynx-sized forest dweller that preyed largely on small, herbivorous mammals, proliferated in North America and gave rise to many new groups, including Machairodontinae - the extinct subfamily that includes sabre tooth cats and their relatives - and Pantherinae - the diverse subfamily that includes all of today’s big cats.

African Wildcat - The Domesticated Cat

Around the same time that the last sabre tooth cats died out in North America (~10,000 years ago), a few thousand miles away in the Middle East’s Fertile Crescent, a group of African wildcats took up residence in a small village.

These cats were accepted by their human neighbours and, soon afterwards, tamed. There are now more than 50 breeds of domesticated cat, all descended from African wildcats.

- How we domesticated the cat

- Scottish wildcat vs the average tabby: Just what's the difference between these similar-looking felines?

Amongst wildcats, the African wildcat - or Felis lybica - is considered the friendliest and most accepting of humans. Others, like the European wildcat (Felis silvestris), behave more like their big cat cousins and prefer to be left well alone.

- Scottish wildcat guide: how to identify, where they live, and conservation efforts

- Rare fossil found of tiny prehistoric cat, so small it could fit in the palm of your hand

- How wild is your cat? 6 key behaviours that reveal the wild ancestry of your cat