Whenever I dreamt of my first encounter with wild monkeys the setting would always be somewhere exotic. Amazonian jungles, shadowed by the dense rainforest canopy, with spider monkeys swinging overhead. Above the clouds in Ethiopia’s highland plateaus, surrounded by troops of grazing geladas. Snowy alpine landscapes in Japan, watching macaques find respite from freezing temperatures in thermal springs. I wasn’t expecting to meet my first non-human primates in a highly urban, densely populated corner of Europe.

“Just up the hill, a couple of hundred metres from the ticket office,” as one friendly local put it – not the kind of tip-off I had anticipated in my quest to see monkeys in the wild.

Car horns and Gibraltar’s bustling dockyard provide the background noise, rather than the evocative calls of parrots, trogons and other colourful birds. But though the setting may lack tropical glamour, it does not take anything away from the thrill of meeting monkeys face to face.

I notice the leaves rustling in the olive trees ahead of me. I slowly edge closer along the dirt path behind a disused military bunker. I freeze 10m from the trees when I spot a pair of eyes glaring out at me through the branches.

I’m staring into the eyes of a Barbary macaque. My initial reaction is to crouch low and back off to give her room, but my presence doesn’t seem to bother her in the slightest.

The macaque rapidly loses interest and continues feasting on the olive foliage. To my joy, a second set of eyes turns to look at me. They belong to a baby, clinging to its mother’s back. His young and comically wrinkled face is fixated on mine and full of inquisitiveness.

While most Gibraltarians know the macaques as ‘apes’ – they fit the ape characteristic of lacking a tail – they are in fact a species of African monkey that appears to be tailless (they actually have a vestigital tail). It is believed that they were first introduced to the Rock of Gibraltar in the 17th century.

Recently, DNA analysis has shown the animals present now are of Moroccan and Algerian descent, disproving previous theories that they are remnants of a much larger population inhabiting southern Europe before the last ice age.

But how did the macaques get to Gibraltar? The locals tell stories of them swimming here, but this is bit of a stretch, given that the Strait separating the continents is 14km wide and swept by strong currents.

There are no records of macaques being brought to Gibraltar, though travelling Moors may have introduced them as pets. At any rate, the macaques have been deeply rooted in Gibraltar’s history since their arrival, particularly since the peninsula was ceded to Britain in 1713. It is said that as long as the macaques stay, the Rock will remain under British rule.

During World War II, Winston Churchill famously found time to leave his war-room duties to order the colonial secretary to find ways to increase the macaque population and “maintain it thereafter”.

And maintained thereafter it was. The population now stands at over 300, split between seven troops. Their lifestyle differs extensively from their relatives across the Strait, however.

In winter in Morocco and Algeria, macaques shiver in icy cedars and huddle to keep warm; a stark contrast to Gibraltar’s population. They also range across wide forested areas, while Gibraltar’s macaques are restricted to a single square kilometre, no higher than 500m above sea level.

Should macaques be fed?

Perhaps surprisingly, there is plenty of wild food on the Rock for the macaques. Their varied plant diet ranges from olive leaves and fruits to the roots of introduced Bermuda buttercups, and this is supplemented with live prey, such as small lizards and numerous invertebrates.

Inevitably, being highly intelligent and adaptable, the monkeys also are fond of human handouts – and therein lies the problem. I hear an approaching vehicle, and the macaques I am watching leave their tree, clearly in search of something.

I follow them through the woodland to a road where we are met by a hoard of tourists. Two minibuses have pulled up and people are flooding out, wielding their smartphones.

Young macaques climb onto the roofs of the buses, with one hanging precariously onto a wing mirror, tapping at the glass. Tourists crowd around macaques to take selfies. One of the bus drivers hands out peanuts.

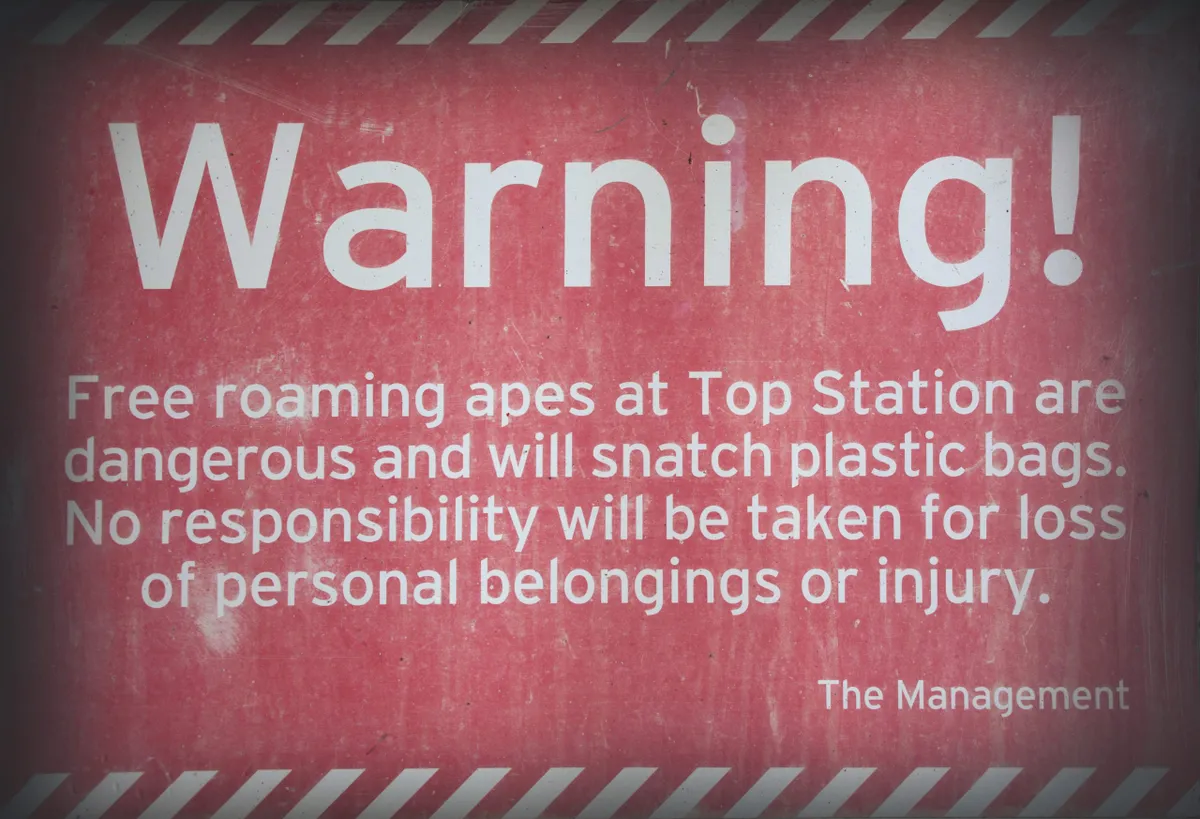

Behind the crowd, signs pinned to lampposts say: “Please do not feed the macaques”, and “WARNING: Feeding macaques is an offence”. Yet here was a tour guide hand-feeding the macaques in front of about 40 tourists. If he’s doing it they must surely be encouraged to do the same.

Small wonder that macaques have developed a reputation for erratic behaviour in Gibraltar. And its tourist boom – the peninsula hosts over 10 million visitors each year – is only making matters worse. The macaques will snatch food from the hands of tourists and steal anything from smartphones to number plates.

They are also renowned for their ferocity, towards both tourists and lower-ranking macaques. The easily available food heightens competition in a macaque troop, increasing aggressive behaviour.

Biting the hand that feeds

The macaques can hardly be blamed, they’re just responding to opportunities we create. “They’re smart animals, smarter than most people think. If they want your sausage roll, they’re not going to ask for it politely,” one taxi driver tells me. “These tourists need to be smart too. If they don’t want their food taken, don’t bring it into the macaques’ home, and definitely don’t get it out in front of them.”

Before my visit to Gibraltar, I read numerous news stories about macaques attacking people and of tourists being bitten. The articles demonised the macaques and victimised the humans.

I also saw people get bitten while I was there. Bites and scratches can lead to severe infection, or even disease transmission, yet each incident I witnessed was down to macaques being fed illegally – they bit only when food was forcefully taken away.

During my stay, the same routine plays out each day: macaques are fed and assert dominance through intra-troop fighting, while tourists become frightened. What’s frustrating is the solution could be quite simple. Better education of tourists could provide both visitors and macaques with a much better experience on the Rock.

I meet local primatologist Brian Gomila, who is the first to organise informative, non-intrusive macaque-watching tours on Gibraltar. Through his organisation, Monkey Talk Gibraltar, Brian offers small-group tours that involve viewing the macaques in wild environments, along similar lines to responsible primate-watching in other countries. “Away from the tourist hotspots, that’s where people should see them,” he says.

“There’s so much more to the macaques’ lives than most people see,” Brian adds. “If only people could adopt a little more patience and let the macaques go about their business, I guarantee they would be able to get just as close as they can at the current locations used by minibus and coach tours. But the beauty of doing it this way is that the encounters would be on the macaques’ terms.”

Brian recognises that close-range encounters may be necessary to satisfy tourists, but believes that the way such interactions take place needs to change. “By keeping a low profile, we can immerse ourselves in their world as they groom, forage and socialise only feet away, without intruding upon them.”

Close-up encounters do have a positive side. They offer great opportunities for public education, for example. Meeting a macaque might even help to inspire the next young Jane Goodall or Gerald Durrell.

Immersed in the macaques’ world

After spending time with Brian I see the macaques in a new light. It would have been easy to come to Gibraltar and notice nothing except what is wrong… the paparazzi-like frenzy with which tourists stalk the monkeys or the taxis noisily roaring around the nature reserve.

But Brian enables me to see past all of this. I’m able to observe macaques grooming one another in the treetops, keeping a watchful eye on their youngsters beneath. I see five-month-old siblings play-fighting on vines before finding myself surrounded by one- and two-year-olds learning the ropes.

Gibraltar is a wonderful place for a naturalist to visit. It sits on a major bird-migration highway, with enormous numbers of raptors and passerines passing through in spring and autumn.

There are plenty of exciting resident species to seek out too, from the blue rock thrush and Barbary partridge to ocellated and wall lizards, with great dolphin-watching in the bay. Above all, however, its macaques are a natural treasure.

Across their North African range, Barbary macaques are in decline: their wild population here may be as low as 6,500 individuals, and since 2008 the species has been classed as Endangered.

Capture of baby macaques for the pet trade has long been one of the main threats, though in a positive step this was banned by the 2016 meeting of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). In Gibraltar, at least, the macaque population seems to be stable.

This is why we must try to preserve the wild nature of the Rock’s Barbary macaques, the only free-roaming non-human primates in Europe. If we can recognise that their lives matter, then our efforts to protect them will be much more effective – and our experiences in their environment will be much more rewarding.

Find out more:

Main image: The Barbary macques of Gibraltar are the only wild monkeys in Europe. © Arnold Monteith

This crossword originally appeared in BBC Wildlife Magazine. Take a look inside the current issue and find out how to subscribe.