The Dutch explorer Jan Huyghen van Linschoten encountered a fabulous and unusual beast while travelling around India in the late 16th century. It was a “fish of most wonderfull and strange forme”, about the size of a “middle-sized dogge”, and had been hauled out of a river in Goa.

It ran around “snorting like a hogge” and was covered in “scales a thumb’s breadth, harder than iron or steel”. When attacked, it rolled into a ball and could not be prised open. Van Linschoten was baffled, though he had seen plenty of exotic wonders. Particularly when the creature unfurled itself and scuttled off to safety. What on Earth was this thing?

Four hundred years later, we can infer that this ‘fish’ was most likely a pangolin. There aren’t any other scaly dog-like creatures living in India. And certainly no fish that can take off at a sprint.

We can even identify what species this might have been. Of the eight pangolin species living in Asia and Africa, only one lives in southern India. Van Linschoten’s fish-dog-pig was probably a long-tailed pangolin, Phataginus tetradactyla.

The eight species of pangolin

Africa:

- Black-bellied (also known as long-tailed pangolin), Phataginus tetradactyla: Vulnerable

- White-bellied (also known as African white-bellied, three-cusped, and tree pangolin), P. tricuspis: Endangered

- Giant ground pangolin (also known as giant pangolin), Smutsia gigantea: Endangered

- Temminck's (also known as cape, ground, and Steppe pangolin), S. temmnickii: Vulnerable (pictured)

Asia:

- Chinese, Manis pentadactyla: Critically Endangered

- Indian (also known as thick-tailed pangolin), M. crassicaudata: Endangered

- Philippine (also known as Palawan pangolin), M. culionensis: Critically Endangered

- Sunda (also known as Malayan pangolin), M. javanica: Critically Endangered

Discover more about pangolins in our guide to these unique mammals.

Why pangolins have a low profile

Of course, the modern method of organising species according to their evolutionary relationships does not correspond with the ways naturalists hundreds of years ago organised nature. Naturalists in 16th-century Europe saw beasts as symbolic things with places in a natural hierarchy. They had moral meanings: many were very clearly ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Pangolins were a little trickier – they seemed to fall between the cracks in this natural order, and appeared to be slippery, ambivalent creatures.

This elusive nature may be why even today pangolins are still so unknown. Though we now know far more about the biology of the animals, mention them to the average person and they will most likely give you a blank stare and ask if they’re some kind of prehistoric creature. Explain that pangolins are animals rather like anteaters with scaly exteriors that can curl up into balls like armadillos, and many folk will suspect you’re pulling their legs.

Such a low profile is rather surprising. These bizarre creatures have been traded for hundreds, if not thousands, of years across Asia and Africa. Pangolins are valued primarily for their meat and uses in traditional medicine.

Their scales are nothing more than keratin, the same material as in our hair and nails, or rhino horn. Yet, in traditional Chinese and Vietnamese medicine they are still falsely believed to possess all sorts of special powers, including aphrodisiac properties.

They’ve recently even been smuggled to the USA because they contain a substance used to make crystal methamphetamine. The black market is seductively lucrative: a kilo of pangolin meat can be worth hundreds of dollars, a kilo of scales thousands of dollars.

Why pangolins were (and still are) eaten

The high-end restaurants cooking foetal pangolin and party people shooting up on scales didn’t exist in the 17th century, but pangolins were used in many similarly weird ways back then. In Java in the 1630s, one Dutch physician met a hole-digging animal with a “cold nature”, covered in carp-like scales. The Javanese apparently called this monster taunah (digger in the earth), while Chinese physicians used pangolins to treat all sorts of ailments.

In the 1720s, another Dutchman in Ambon reported an animal called a panggoeling, with an “extremely hard and scaly hide that the Chinese and Javanese used to make armour… and would also eat its sweet flesh”.

Pangolins have now been so extensively hunted that all eight species are threatened. Several are but a scale’s breadth away from being lost forever. Pangolin products were comprehensively banned under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) in 2016, but this has not slowed the increases in illegal killing or highly organised international trade.

Pangolins have the dubious honour of being the most trafficked mammals on the planet, yet in Europe we barely know they exist. So many cultures around the world are familiar with them, but why have these animals remained comparatively unknown to us? It’s a question that we need to answer quickly. Strong public support will be vital in helping prevent pangolins from being poached out of existence.

The harlequin nature of pangolins

For hundreds of years, pangolins have both fascinated and confused Europeans. But have their hybrid natures prevented them from becoming ‘familiar’ exotic creatures, such as elephants or lions? Pangolins have always been enigmatic beasts, with many guises. Early European explorers came across them under many names all over the world: lin in Siam (now Thailand); pangoelling in China, Sumatra and Java; allegoe in the Malabar region of southern India; and quogelo in Guinea.

These creatures had harlequin natures – a bit fish-like, somewhat mammalian and definitely reptilian. In Siam in the 1680s, one French missionary was fascinated by a scaly “hedgehog” that seemed to be a reptile, but, confusingly, also bore live young that rode on the mother’s tail. Female pangolins have only one baby at a time, which hitches lifts in a way you’d imagine that only animals in Disney films might do.

These tricky creatures could be very troublesome or very helpful. In Dutch colonies in the East Indies (now South-east Asia), pangolins were seen as pests, undermining stone floors and digging under colonial buildings. They were called, appropriately, ‘Devils of Taiwan’ (Taywansche Duyvel).

A menagerie in Amsterdam in the 1700s advertised a duyvel on show. But it was stuffed rather than alive: the specimen had been killed due to its obnoxious habit of digging through stone.

In contrast, a cartographer in Guinea reported that “one finds in the woods an animal with four feet” called a quogelo, its scales “like the leaves on an artichoke”. It defended itself by gathering into a ball, protected by iron-like armour. It was, the cartographer wrote, “not the least bit naughty or malign” and helped keep pesky insects at bay. He would rather have liked one as a pet, though he also reported that they tasted surprisingly good, despite the “musky” ants they ate.

Pangolin tongues are indeed the longest relative to body size of any mammal, reaching up to 40cm in the larger species. Very useful for extracting ants from their nests.

Why pangolin skins were trendy in Europe

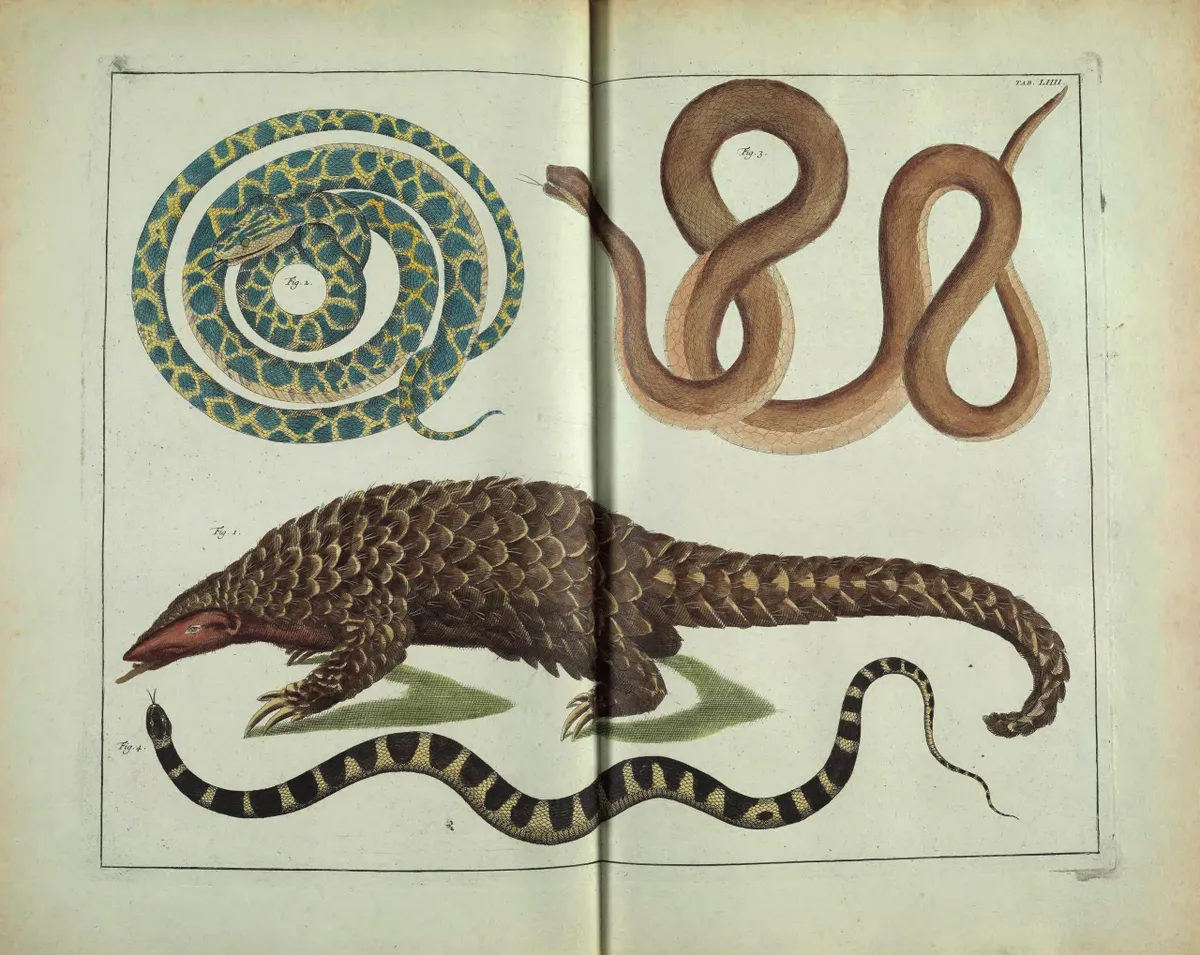

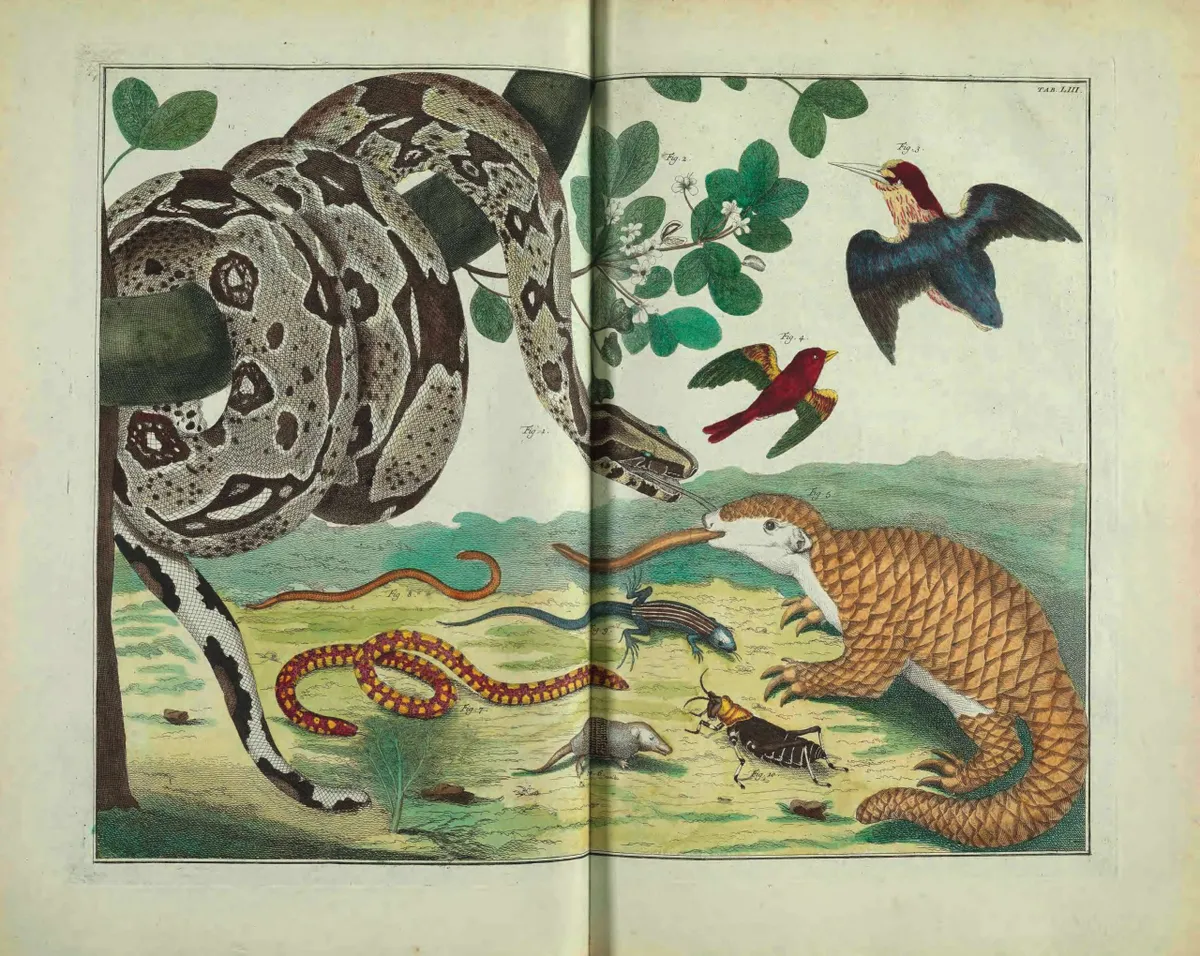

In the 17th century, the strange scaly skins of pangolins arrived in Europe more often than the living animals. They must have been popular and plentiful, because you can find them in most of the collection catalogues of the time. Pangolin skins were one of the trendy items of early modern Europe: all the cool collectors wanted one, but nobody quite knew what to do with them.

The pangolins were usually just labelled as “scaly Indian lizards” and hung on a wall. Perhaps, in an era when European global power was rapidly expanding and there were ever-growing piles of new things to wonder at, an ambiguous object that was so self-evidently marvellous and at the same time not especially valuable didn’t merit too much attention.

The unusual skins, and vague descriptions of scaly exotic beasts in travel journals and natural histories, did lead to significant confusion, however. There was, in fact, another type of carapaced beast from the ‘Indies’: armadillos from the West Indies (now the Caribbean) were also very popular and easy to preserve for collections.

Both pangolins and armadillos came from distant lands then known as the ‘Indies’ (albeit far apart, to the west and east of Europe), both were unusually armoured and both had elusive, hybrid natures.

Why pangolins were thought to be similar to armadillos

Seventeenth-century scholars trying to understand new species that they encountered tended to use textual descriptions to guide them. Pangolins and armadillos were extremely similar on paper. The origins of objects in collections were also often unclear as information was lost along complicated global trade routes. In this text-based culture, which was experiencing a tsunami of novelty from all over the world, there was inevitably going to be some confusion.

The fact that these animals seemed to exist between nature’s categories did not make the armadillo and pangolin all that difficult to deal with. For this was a time when the universe was believed to be governed by very different rules to our own.

There were many inventive ways to explain things. For example, the 17th-century scholar, Athanasius Kircher, argued that armadillos were the hybrid offspring of the tortoise and the hedgehog that had been cooped-up together on Noah’s Ark. No doubt, had Kircher touched on the pangolin, he’d have posited that another, more gamesome hedgehog had snuck overboard and had a passionate fling with a fish.

The armadillos and pangolins seemed to be a link in the chain of nature that many naturalists had rather expected to exist: a bridge between furry beasts and scaly reptiles and fish. These creatures played the same role in nature and became equivalent in the eyes of European naturalists as the lizard-mammals that bridged a big divide in the natural order.

At the start of the 17th century, there were definite accounts of “scaly lizards” in the East Indies, Taiwan, India and Goa, and of armadillos in the West Indies, Brazil and ‘America’. By the end of the century, these earlier books had been compiled into collection catalogues or encyclopedias that tried to include all creatures in existence. The scaly, armoured, ball-rolling, reptile-mammals from the two Indies, eastern and western, started to get confused.

The prolific Dutch collector Albertus Seba, for example, described specimens of the “African armadillo” and “Oriental armadillo”. He also pictured pangolin skins, labelled “armadillos”, from Brazil, Java and Taiwan.

The armadillo and pangolin had become pan-global scaly mammals, the exotic taxonomic oddities that helped or hindered colonial operations in the Indies of East and West. It was only in the late 18th century that they finally became disentangled again.

Can pangolins be saved?

Their odd, hybrid natures made pangolins, or ‘scaly lizards’, into indistinct creatures in European eyes. It seems they still are. Perhaps people’s intuitive ways of understanding nature change little over time: species that don’t fit easily into categories confuse us.

Creatures that were more practically useful, such as whales, or of higher status, such as lions and giant pandas, became more ubiquitously familiar and are now higher up the conservation priority list. There is also the unfortunate fact that cute and cuddly tends to win public hearts over the scaly and reptilian.

We might, however, be able to use the pangolins’ strangeness to their advantage. For something else that hasn’t changed is our fascination with the monstrous and bizarre. There might – just – be enough desire to stop the world’s more unusual inhabitants from disappearing, for the very reason that they show us just how fantastical nature can be.

Perhaps we need to harness that sense of the marvellous so familiar to 17th-century travellers and naturalists in the ever-expanding, wonder-filled world they inhabited. Strange and seemingly fabulous creatures such as pangolins, which after all resemble bizarre animated pine cones, might yet help us to preserve our magic-filled world today.

This feature was originally published in BBC Wildlife Magazine. Look inside the current issue and find out how to subscribe.

Main image: Ground pangolin (also known as Cape pangolin or Temminck's pangolin) foraging during the day in Zimbabwe. © Christopher Scott/Getty