Like all lemur species, ring-tailed lemurs are endemic to Madagascar, an island off the coast of East Africa.

Lemurs are the world’s most endangered group of mammals; they are even the world’s most endangered group of vertebrates.

The 2020 IUCN Red List update found that 98% of lemur species are Endangered, and 31% of species are Critically Endangered, which is one step away from Extinction in the wild. Ring-tailed lemurs are listed as Endangered on IUCN Red List.

Learn more about ring-tailed lemurs in our expert guide by the Lemur Conservation Network:

What is a ring-tailed lemur?

The ring-tailed lemur is a medium-sized primate that is about the size of a house cat. Adult male and female ring-tailed lemurs weigh from 3–3.5 kg.

In the wild, ring-tailed lemurs can live about 20 years. They are the most commonly found species of lemur in zoos, where they can live up to a decade longer.

What is the scientific name of the ring-tailed lemur?

The scientific name of the ring-tailed lemur is Lemur catta.

Ring-tailed lemurs are a type of strepsirrhine primate. This group includes lemurs, lorises, and galagos. They are also known as the “wet-nosed” primates.

Lemurs are also members of the prosimian group, a frequently used classification that includes all strepsirrhines as well as tarsiers.

Where do ring-tailed lemurs live?

All species of lemurs are endemic to Madagascar, the world’s fourth largest island. Ring-tailed lemurs live in the southern and southwestern regions of Madagascar. Here, summers are hot and wet, winters are cold and dry, and rainfall is variable.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Twin Baby Ring Tailed Lemurs | Madagascar | David Attenborough | BBC Earth

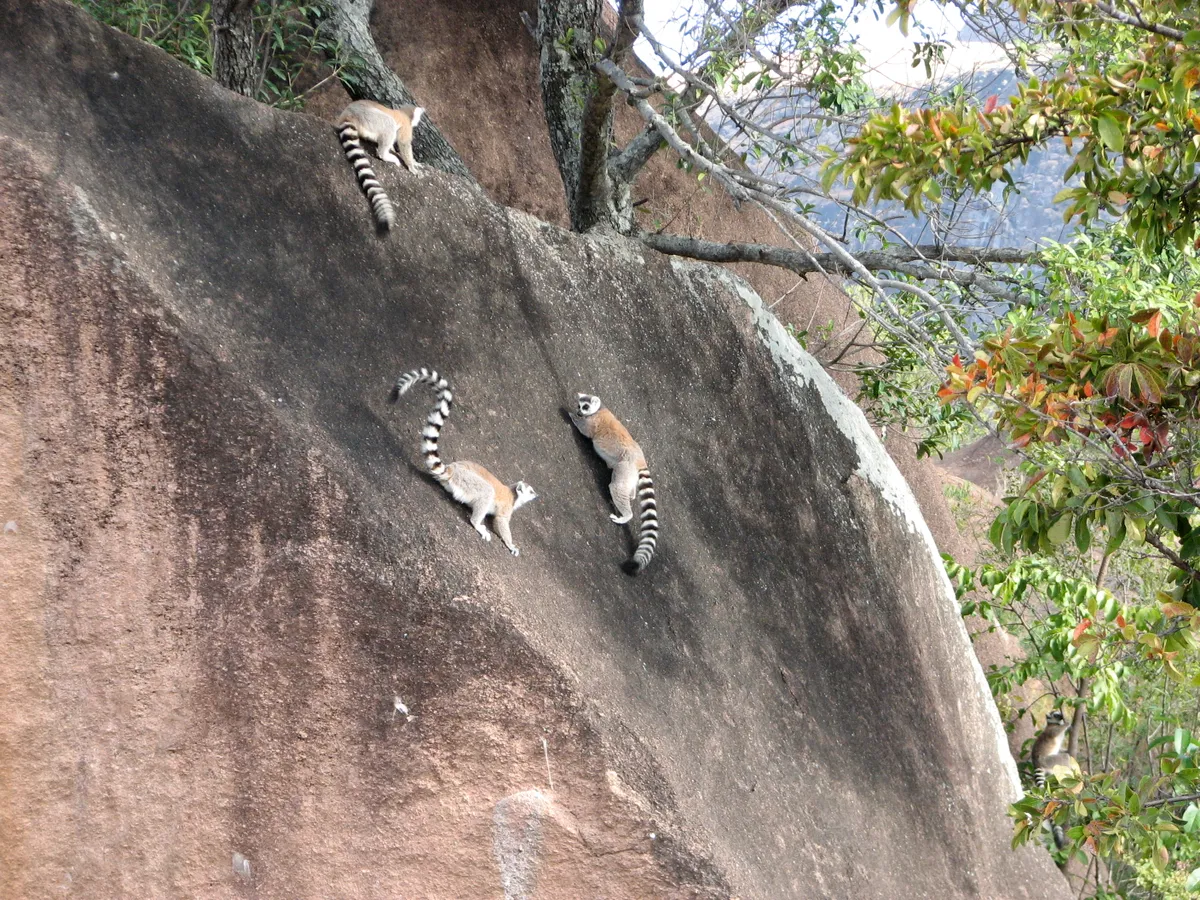

Ring-tailed lemurs are an ecologically “flexible” (or, adaptable) primate. This means they can be found in a diverse range of habitats, including rocky outcrop forests, gallery forests, deciduous forests, spiny forests, and open anthropogenic (human-impacted) savannas.

Some ring-tailed lemurs are even known to use caves, possibly to escape the heat, and steep cliff faces to avoid predators.

Perhaps their most extreme habitat is the spiny forest. Here, temperatures are high and resources are often scarce. Madagascar’s spiny forest is very unique, as similar forests are not commonly found elsewhere. It is dominated by thorny plants and short trees and has little shade. The cactus-like plants offer the ring-tailed lemurs a sticky sap to eat which is rich in fat. Over many generations, these lemurs have learned how to navigate safely through the spiny plants in this region.

What is unique about ring-tailed lemurs?

Ring-tailed lemurs use their tail to flirt!

The most recognizable feature of the ring-tailed lemur is its black and white striped tail, which is about 60 cm long. Ring-tailed lemurs have glands on their wrists (called “antebrachial” glands) that secrete pheromones (a type of chemical signal) that they rub onto their tails and waift into the air. This is called “stink flirting”.

Males have horny spurs that cover these glands. They use them to scent mark objects in their territory, including leaves, sticks, and even whole tree trunks!

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Lemur's Scent Attracts Females | Animal Attraction | BBC Earth

Ring-tailed lemurs can smell really well!

Like all strepsirrhines, ring-tailed lemurs have primitive cranial (skull) features, including a relatively small braincase for a primate. They also have a long nose with a very well-developed sense of smell. Strepsirrhines are unique, too, in that they exhibit the same kind of reflective “eye shine” seen in many other mammals at night, including deer and foxes.

Ring-tailed lemurs have unique teeth!

Lemur species, including ring-tailed lemurs, also have a “toothcomb”. In this unique dental adaptation, the lower incisors and canines have compressed tightly together. Lemurs use their toothcomb for grooming themselves and other group members. They have nails on their hands and feet with the exception of their second toe. This “toilet-claw” is used for self-grooming.

When are lemurs active and how do they move?

Ring-tailed lemurs are diurnal, meaning they are most active during the day. They are the most terrestrial species of lemur, though they frequently spend time feeding, traveling, and sleeping in trees. These lemurs primarily move around quadrupedally (on all four limbs) both on the ground and in trees. They are also accomplished jumpers!

During the day, ring-tailed lemurs can frequently be seen basking in the sun with their arms outstretched. This is often referred to as “sun worshiping”. To keep warm while sleeping, the group curls closely together in “lemur balls”.

What do ring-tailed lemurs eat?

Ring-tailed lemurs are frequently classified as frugivore/folivores or omnivores. They eat fruits, flowers, leaves, bark, sap, insects, and occasionally soil for its minerals. Their diet generally reflects the habitat they are living in and the season (wet season versus dry season).

Ring-tailed lemurs are also important seed dispersers. When lemurs eat fruit, they also eat the fruit’s seeds. The seeds then pass through the lemur’s digestive system without breaking down, and wind up back in the forest in their feces. Eventually, many of these seeds grow into new trees!

What is a group of ring-tailed lemurs called?

Ring-tailed lemurs live in large social groups called “troops”, which can have as few as three and up to about 30 individuals. Upon sexual maturity, males join different groups. Females stay in the group into which they were born.

Ring-tailed lemur society is female-dominant. Female lemurs have grooming and feeding priority, including first access to high priority foods like fruits.

Troops hold territories, and each troop must defend their territory when others intrude. These skirmishes are led by the females, during which their babies need to grip on tightly.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Territory Battle | Babies on the Front Line | Cousins | BBC Earth

What are baby ring-tailed lemurs called?

Baby ring-tailed lemurs are called pups. Babies are typically born between September and November, and for lemurs, twin births are pretty common!

Female ring-tailed lemurs may give birth as young as three years old, with their gestation (pregnancy) lasts around 141 days (compared to about 280 days for humans).

When a ring-tailed lemur baby is first born, it clings to its mother’s chest. After a few weeks, the baby is strong enough to be carried on her back. Adult females play an important role in childcare for the entire troop, and often pitch in to help out all of the juveniles.

How big is the range of a ring-tailed lemur troop?

The size of a troop’s home range depends on the availability of the area’s resources, like food and water. Troops living in “richer” forests with greater and easier access to fruiting trees often have smaller home ranges than those living in more open habitats like savannas.

Ring-tailed lemurs “scent mark” plants in their territory to let neighbouring troops know an area belongs to them.

Are ring-tailed lemurs endangered?

Since 2014, ring-tailed lemurs have been classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List, and populations are decreasing.

Why are they endangered? What dangers do they face?

Natural predators

The most common natural predator of the ring-tailed lemur is the cat-like fossa (also spelled fosa; Cryptoprocta ferox). This carnivore lives in many areas across Madagascar and frequently hunts lemurs in trees. Lemurs (especially infants) are also hunted by large birds of prey, including the Madagascar harrier hawk.

Ring-tailed lemurs use various anti-predator strategies, including keeping a lookout and using alarm calls to alert each other. However, the natural predator-prey dynamic is important in any ecosystem. In Madagascar, it is not a major concern for the sustainability of lemurs.

Habitat loss

The greatest threat facing wild ring-tailed lemurs is habitat loss. Madagascar is regarded as a biodiversity hotspot. In southern Madagascar where ring-tailed lemurs live, slash-and-burn agriculture is common. This can result in out-of-control fires sometimes entering protected areas, including national parks and reserves.

When habitat is lost, the forests where lemurs live become fragmented and patchy. This makes it more difficult for males to join other troops, which lowers genetic diversity. Genetic diversity is necessary for species survival, because it allows animals to adapt to changing environments and diseases.

Poaching

Ring-tailed lemurs are also in danger from both the bushmeat and pet trades. In fact, ring-tails are the most common lemur in illegal captive settings like hotels and tourist destinations. As primates, lemurs are susceptible to many human-transmitted diseases, including COVID-19, especially when kept as pets or in close contact with tourists.

Climate change and severe weather

Severe weather events like droughts frequently hit southwestern Madagascar. And, the north is often hit by dangerous cyclones. These can limit preferred food sources for lemurs like fruiting trees. Severe weather also increases poaching because local communities face more extreme food shortages and therefore need to rely on the forest to feed their families.

How are people working to save lemurs from extinction?

Hope is not lost for ring-tailed lemurs! Conservation efforts to preserve Madagascar’s forests are an utmost priority for both Malagasy and International scientists. Today, there are 43 protected areas managed by the Madagascar National Parks association, with research underway to explore potential additions.

Many local and international organizations are working to protect lemurs using conservation strategies and scientific research. Some work to rehabilitate ring-tailed lemurs saved from the illegal pet and bushmeat trade. Others monitor parks and reserves, and plant trees for reforestation. Additionally, the ring-tailed lemur is the most common lemur species found in zoos. Due to successful captive breeding programmes, the population in these facilities continues to grow.

And, like in all biodiversity hotspots, local people are key to successful conservation. So, it’s important for Malagasy people to have opportunities for higher education and scientific training. Madagascar’s local scientific community must be supported to ensure the island’s biodiversity is protected for future generations.

How can you help ring-tailed lemurs?

Ecotourism is a great way to see wild lemurs in Madagascar. Tours within the national parks (once COVID-related travel restrictions are lifted) are a way to directly contribute to conservation efforts and community engagement.

If you can’t make it to Madagascar, you can find ring-tailed lemurs in zoos across the world! Supporting accredited zoos that maintain captive lemur breeding programmes is an important contribution to protecting the species.

Don’t take or share lemur selfies, and stay at least 7 meters away!

If you do have the opportunity to meet a lemur, please avoid up-close “lemur selfies,” for both your safety and theirs. Because lemurs are primates and closely related to us, we can transfer diseases to them (including COVID-19). Like any animal, if you try and touch a lemur, it may become frightened and bite you.

And, sharing photos with lemurs close to humans gives the message that lemurs make good pets. However, lemurs are wild animals and not domesticated and are not suitable to be kept as pets. Infant lemurs raised in isolation (as most pet lemurs are) often develop abnormal social behaviour and become aggressive.

So, only take and share photos of lemurs by themselves or with you seven meters or more away from it. This helps limit our impact on their lives in nature and in conservation centres like zoos.

The Lemur Conservation Network (LCN) unites over 60 conservation organizations working to save lemurs from extinction. LCN works to educate the public about lemurs, raise awareness for their conservation, and promote the people and organizations working to save them from extinction.

LCN was founded in 2015 as a project of the Madagascar Section of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)'s Primate Specialist Group. In 2021, LCN became a registered not-for-profit organisation in the USA.

Main image: A ring-tailed lemur family. Photographed in captivity. © Mathias Appel