When contemplating epic animal migrations, the first journeys that spring to mind will invariably

be the massed movement of wildebeest across the African plains, the globetrotting adventures of Arctic terns, or the oceanic odysseys of gray whales. But let’s not forget the annual cycle of the monarch butterfly, which is surely as impressive as anything an antelope, bird or whale can muster.

In possession of two pairs of brilliant, large orange-red wings, etched with black veins and decorated with white spots along dark margins, the monarch recognised and best-loved of all North American butterflies. Rarely lasting for longer than a month on the wing, the monarchs nonetheless provide an important service pollinating countless wildflowers over the summer.

How far do monarch butterflies migrate? And how do they know where to go?

However, with the arrival of autumn, a special ‘Methuselah generation’ of monarch butterflies, which can live eight times longer than their predecessors, emerges from summer breeding grounds across Canada and northeastern USA.

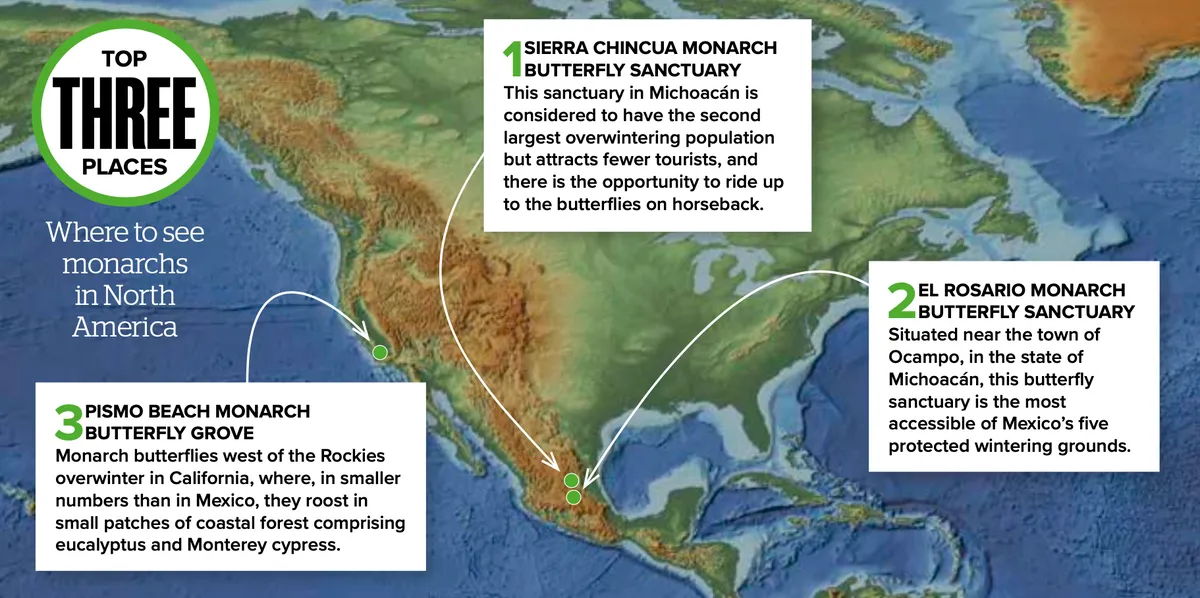

Forced south by decreasing day length, lower temperatures and fewer nectar sources, the final winter destination for these butterflies consists of just a few hectares of high- altitude forest in south-west Mexico, up to 4,800km away from where they started life as an egg.

Migrating only during daylight hours, the butterflies will travel anywhere between 148km and 185km per day, with their speed dependant on wind direction and uplifting thermals. Gliding and flapping their way steadily south, coalescing into super-flocks en route, they’ll pour across the USA-Mexico border before making a ‘butterfly-line’ for the forests of oyamel fir trees situated west of Mexico City.

How monarch butterflies know where to go is the source of considerable debate. Each migration is undertaken by a new generation, meaning they’re unable to learn the route from others, so it must

be genetically hardwired. It’s also believed their antennae have circadian ‘clocks’ that tell them when to migrate, while navigation may well be accomplished by using their compound eyes to calculate the sun’s position above the horizon.

Upon arrival at their wintering grounds, any time from mid-November, the butterflies begin clustering together, with each tree’s trunk, branches and needles often blanketed in tens of thousands of roosting butterflies.

Situated at elevations between 2,400m and 3,600m above sea level, these forested hillsides provide the ideal microclimate for the butterflies, with temperatures varying between 0°C and 15°C, and the humidity level in the understory ensuring that they don’t become desiccated. The butterflies hang almost motionless in a semi- dormant fashion, eking out the winter on their fat reserves.

Come February, when the warmer temperatures and longer days arrive, the forest airspace turns thick with fluttering butterflies. From March, this Methuselah generation heads part of the way back north to warmer climes, landing in states such as Texas. After mating, the females’ final act is to lay their eggs on the nearest patch of milkweed – the larvae’s foodplant. The caterpillars hatch, feed and pupate, and

the freshly emerging imagoes (adults) then move several hundred kilometres further north before repeating the entire life-cycle again. Each successive wave of monarchs is capable of metamorphosing from egg to imago in just five to seven weeks.

Working steadily north, via this step migration, it’s thought it could take as many as five generations before the monarchs ultimately repopulate Canada – from British Columbia in the west to Newfoundland in the north-east. This means that, in some cases, the monarchs returning in the spring will be the ‘great-great-grandchildren’ of those that left the previous autumn... pretty impressive for an animal weighing no more than a paperclip!

Main image" Monarch butterfly © Getty Images