The robberfly family have adapted behaviourally, morphologically and physiologically to ensure that they remain at the top of their game. They are deadly predators, venomous machines, stealth assassins as well as having the best hipster moustaches of the fly world.

The robberflies are formally called Asilidae, which translates literally as gad fly. This initially struck me as odd, as it is the horse flies that have the common name of gad flies, but further investigation reveals the meaning comes from the Middle English word gadling, meaning wanderer or vagabond.

Nowadays the meaning is closer to flitting around in search of pleasure and it makes me wonder what Linnaeus had in mind when he named them so – was it their amazing aerial abilities he homed in on?

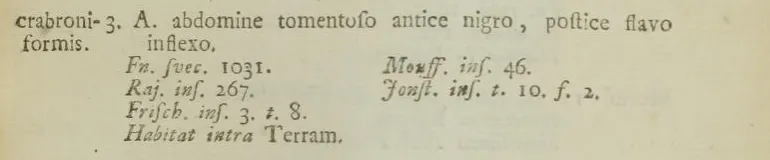

Linnaeus described the Asilidae in his magnum opus Systema Naturea in 1758 (although the family name came along much later in 1812) with the type species for the genus Asilus being Asilus crabroniformis – one of the UK’s most charismatic animal (see below).

Linnaeus’ original Latin description describes them as Os Rostro corneo –literal translation ‘horny beak bone’ – with reference to their magnificent proboscis, a prominent feature of this group. This specimen, from which Linnaeus made his – rather short – descriptions, is now kept safe in the vaults of the Linnaean Society (though I have had the pleasure of seeing them!)

Yet within the collections of the Natural History Museum, there are even older specimens of Asilus crabroniformis. These specimens may be flatter than average as they are preserved within the pages of a book.

They have kept their colour marvellously despite being caught as long ago as 1680 in the gardens of Hampton Court Palace. These may be the earliest examples of this species, and the data we have on them is all thanks to the royal gardener Leonard Plukenet.

The original figure of 11 species of robberfly that Linnaeus initially described has now grown to a figure of more than 7,500 species. This is impressive, when you consider that this is much larger than 6100 or so described species of mammal.

They are one of the most species-rich dipteran families, though this may be due to a sampling bias because of their obvious appeal to Dipterists – we are not immune to being taken in by these large and charismatic creatures.

This is reflected in the diversity of species and the number of specimens of the Natural History Collections, as within this collection there are 339 drawers, there are nearly 3,000 species of these beasties, and 2,300 type specimens.

The UK boasts 28 species of Asilidae, which may not seem like a lot in terms of flies, but hold on – we have only 30 native terrestrial mammals, of which 17 are bats.

Adorned with moustaches and powerful piercing mouthparts, these predators are aptly named, as they truly are the most vicious and effective aerial predators.

These flies are venomous, probably both as adults and as larvae (although we know so very little about the offspring). The adults are able to catch, then sedate their prey whilst on the wing, suck out the contents and then drop the husk of what was once a living breathing entity. It’s almost poetry.

The average size of the hornet robberfly is 2.5cm in length and they have distinctive features that help identify them. The adults have enormous bulbous eyes, one of the many tools that make them such efficient predators, and the distinct dip between the two eyes that are both characteristic not just of this species but of all of the family.

They can swivel their heads around and their eyes can see what’s going on behind them as well – it is hard to go undetected by this predator.

Another characteristic of this species (and most of the family) is a well-formed, stout beak often hidden in a luxurious moustache or, more correctly termed, a mystax. It is the needle-like mouthparts called the hypopharynx that pierces their prey.

This is not for the faint-hearted, as they often try and pierce the soft parts of the insect, such as the neck or sometimes the eyes. Luckily for the fly this moustache helps protect their mouthparts from being damaged by the flailing prey.

The prey don’t have to flail for long, though, as the fly injects saliva that contains nerve toxins that paralyse the prey, and proteolytic enzymes that dissolve the insides.

They are nasty for insects, spiders, and occasionally a very unfortunate hummingbird, but apart from giving a nasty jab, they are not dangerous to us humans (see below).

Research done back in the 1960’s found that injecting robberfly saliva into invertebrates kills them instantly, but they never inject venom into humans – can you imagine being the guinea-pig for this study.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention another distinctive morphological character -the genitalia. The males have large and conspicuous genital parts but for once it’s the females’ genitalia that is the more visually arresting feature giving her the characteristic hornet-like appearance (see below).

And blimey, it’s an impressive large and shiny ovipositor (egg laying tubes) to enable her to insert her eggs into a nice patch of fresh dung.

Now this is where it gets tricky, as we know less about the egg and larval stage than we do the adult stage. And this is the main reason why we should be concerned about these gorgeous creatures as these are rare. In fact, several of our UK species of robberfly are protected, including the hornet robberfly.

The eggs are laid in or under the old dung of cows, horses and rabbits, and soil nearby and in being so are reliant on farming practices as well as large mammal management.

Buglife write on their site that it is the change from cattle to sheep as well as undergrazing on nature reserves that may have impacted on the hornet robberfly population.

There was much concern about livestock wormers (or rather dewormers), and how some render dung poisonous to insects which is believed to be one of the reasons for the decline in the fly (due to their prey disappearing). But maybe the adults (and subsequent larvae) are more flexible in their habitat requirements?

As to what the larvae feed on, it is thought to be dung beetles but again this has only been observed (and not by many authors) during late-stage instars. What do the little ones eat? It is a UK priority species and we need to know more about it.

How can we consider conserving a species (if it needs it) if we don’t know where it is or what it’s getting up to? It’s like a wayward teenager.

The hornet robberfly has a degree of protection due to being listed in the NERC Act Species of Principal Importance, but and some of the other species are red-listed but this doesn't strictly speaking mean that they are protected.

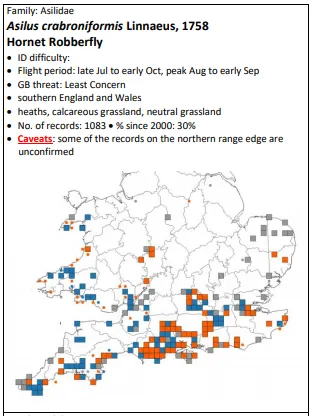

Martin Harvey runs the UK recording scheme for these wonderful little animals believes that this species is doing okay in England at the moment, but there have been rather few recent records in Wales, and not much sign of any recovery in areas such as Norfolk where it used to occur (see below).

And sadly, the current chairman of the Dipterists Forum, Rob Wolton, has been with the Devon Fly group looked for it recently in some of its traditional haunts in Devon but failed to find it.

What we really want now is more information of this species. Personal observations in the field, the location of eggs and the like, and species distributions are all critical in ensuring that we maintain and enhance our existing populations.

Please read about the UK recording scheme for these flies (see below or visit the website) and you can send all your sightings and records to that site. Martin also runs many courses on these as do others in the Dipterists Forum, so sign up and go along to them.

Asilus crabroniformisis one of most enigmatic species and I hope remains to be so for many years yet.

Dr Erica McAlister is the senior curator of Diptera at the Natural History Museum of London, a committee member of The Dipterists Forum and president of the Amateur Entomologists' Society.

The Dipterists Forum, a UK organisation dedicated to all things fly, is actively involved in collecting, recording and researching our UK species - most of which are not restricted to just the UK. The distribution records help us understand population distributions and change associated with climate and land use. It is essential for us to get out there and help.