Filled with stunning animals and intricate polyp-algae colonies, coral reefs are often considered to be one of the world’s most beautiful ecosystems, and receive thousands of tourists every year visiting to admire these complex habitats.

But what is coral made from, what is the ‘coral bleaching’ that we hear about in the news and what causes it, and what are the different types of reef?

Conservationist and author Mark Carwardine discusses how coral reefs are formed and species to look out for:

What is coral?

It may look like a plant but it is an animal, related to sea anemones. A tiny, soft-bodied creature called a ‘polyp’, it lives with thousands of other polyps to form a colony.

So-called hard coral polyps extract calcium carbonate from the seawater and use it to build exoskeletons to protect themselves. They build on the exoskeletons of their ancestors and, as the centuries pass, the coral reef slowly grows.

How are algae involved in coral reefs?

Reef-building corals would not survive without the microscopic single- celled algae (zooxanthellae) living inside their tissues. In this remarkable symbiotic relationship, the coral provides the algae with a home and nutrients for photosynthesis (from its own metabolic waste) and, in return, the algae provides the coral with food (to supplement the food it scoops out of the seawater). It is these extra nutrients that enable the coral to build reefs.

What is so special about coral reefs?

It would be hard to exaggerate their importance. Teeming with life, they support more species than any other marine environment and even rival rainforests in their biodiversity. They act as natural barriers, support fishing industries and communities, provide employment through tourism, and much more. Yet all the coral reefs in the world together cover an area no bigger than France.

Please note that external videos may contain ads

Incredible Life in the Red Sea Coral Reef | BBC Earth

Why are coral reefs under threat?

Coral reefs are fragile ecosystems. Major threats include pollution, fishing with cyanide and dynamite, overfishing, coastal development, collection for the pet and curio trades, coral mining for building materials and sedimentation. According to WWF, roughly one-quarter of coral reefs worldwide are already considered damaged beyond repair, and most of the rest are under serious threat.

What is coral bleaching?

The symbiotic algae are highly susceptible to changes in their environment – it doesn’t take much for them to stop producing food and die. Then they are ejected from the coral. If they go, so do their vibrant colours and all that’s left is the coral’s white skeleton. This is ‘coral bleaching’.

Many environmental issues cause it, but the single biggest factor is rising sea temperatures due to global warming. Coral reefs are already operating very near to their upper limit of heat tolerance, so small rises of just 1–2oC above the norm for a few weeks at a time is enough to cause bleaching.

Over the past few decades bleaching has become more frequent, more intense and more widespread, leading to massive die-offs around the world. As well as a shocking amount of regional bleaching, there have been Global Bleaching Events. Experts predict that if greenhouse gas emissions are not drastically reduced, these events will become routine.

Can coral reefs recover from coral bleaching?

Yes and no. The polyps can catch their own food and survive for a short time without the algae, but they ultimately die themselves if they can’t find replacements. The problem is that they need time – full recovery can take as long as a decade. If the temperature is too high for too long, or it peaks too often, the chances of survival are slim. And, if the reefs die, everything else dies with them.

What is super coral?

‘Super coral’ is a term coined as scientists search for innovative solutions to the coral bleaching crisis. Just as we have bred domestic animals for desirable features – speed in greyhounds, for instance – it might be possible to breed corals that are more tolerant to ocean warming.

There are various ways to achieve this. Scientists can cross hardy types of coral together; use genetic engineering to enhance heat tolerance; inoculate corals with bleaching-resistant symbiotic algae or even ‘train’ corals in tanks by exposing them to heat. We can also collect and breed from wild corals that have survived bleaching events.

While it’s important to explore all options to help save our reefs, super coral is not ultimately a globally scalable solution. Super corals could be replanted to help repair individual reefs, but replanting the entire estimated 250,000km2 of coral habitat that exists across our oceans would be like trying to regrow the world’s forests from seedlings.

This originally appeared as a Q&A in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Emma Kennedy.

Are there any coral reefs in the UK?

Corals are certainly not confined to the shallow, sunny waters of the tropics. More than half of around 5,000 known species of corals live in cold and deep waters. The main reef-forming coral in UK waters is a bushy, white species, Lophelia pertusa, or Desmophyllum pertusa as some scientists prefer to call it.

Mostly located off the west coast of Scotland, Lophelia reefs are found from around 150m deep and are very slow growing. A huge reef off the coasts of Barra and Mingulay in the Outer Hebrides covers more than a hundred square km and is thought to be over 4,000 years old. In the Rockall Trough, 160 km north-west of Scotland’s Cape Wrath, the Darwin Mounds are thickets of Lophelia, as well as another species Madrepora oculata.

Similar to tropical reefs, coldwater reefs form important habitats for many fish and have been heavily targeted by deep-sea trawlers. Darwin Mounds were badly damaged before they were protected in 2004.

This originally appeared as a Q&A in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Helen Scales.

Please note that external videos may contain ads

Protecting Scotland's Coral Reefs #OurBluePlanet | BBC Earth

- Seashells expert guide: what are they, where do they come from, and how are they made?

- Emperor penguin guide: where they live, how they breed and how they survive the cold

- New species of fossilised sea creature described

- Puffin guide: what they eat, when they breed and best places to see puffins in the UK

What's the difference between fringing reef, atoll and barrier reef?

Fringing reefs (pictured above) are attached to a shoreline and are the most common type of reef, particularly in the Caribbean. They are easy to access from the beach, but their proximity to land makes them vulnerable to pollution.

Atolls (pictured above), in contrast, are circular or horseshoe-shaped rings of reef, comprising a tough band of coral around a sandy lagoon. They are often found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and look spectacular from above.

Barrier reefs lie (pictured above) away from the shore, separated by a deep lagoon. From above, they appear long and thin (a ‘barrier’ between ocean and land) and can drop steeply off the continental shelf. The lagoons vary in width – Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is 200km from the shore in some places.

Understanding coral structures (morphologies) has helped scientists to map reefs and work out how they develop over geological time periods.

This originally appeared as a Q&A in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Emma Kennedy.

Species to spot on a coral reef

Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

Listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, the hawksbill sea turtle (sometimes shortened to hawksbill turtle) is distinguished from other sea turtles by its sharp, curving beak which it uses to fed on sponges, sea anemones and jellyfish. It has overlapping scales on its shell, and a serrated-look on the edges of it shell. The shell is often sold as ‘tortoiseshell’ in markets, and the trade of hawksbill sea turtles and products derived from the species is regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

Pygmy seahorse (Syngnathidae family)

Nine species of pygmy seahorse in the Syngnathidae family have been described to date, with the first only being described by scientists in 1970. As the name suggests, these are very small seahorses, usually less than 2cm in height – occasionally other small seahorses are called pygmy seahorses but do not belong to the same family.

These seahorse species are very well camouflaged amongst the seagrasses and corals in which they live. Like other seahorses, the female expels her eggs and passes them over to the male who broods them.

Rabbitfish (Siganus spp.)

While it’s clear that many fish seek out each other’s company, they don’t tend to nurture relationships with their shoal- mates. Rabbitfish are a rare exception. These colourful coral-reef fish team up in pairs, often with members of the same sex, suggesting these partnerships are about more than reproduction.

Their preferred foraging technique of probing cracks and crevices in the reef for algae and sponges makes it hard to keep an eye out for predators while feeding. So members of a pair take turns to eat while their partner remains out in the open to quite literally watch their backs.

This Q&A originally appeared in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Stuart Blackman.

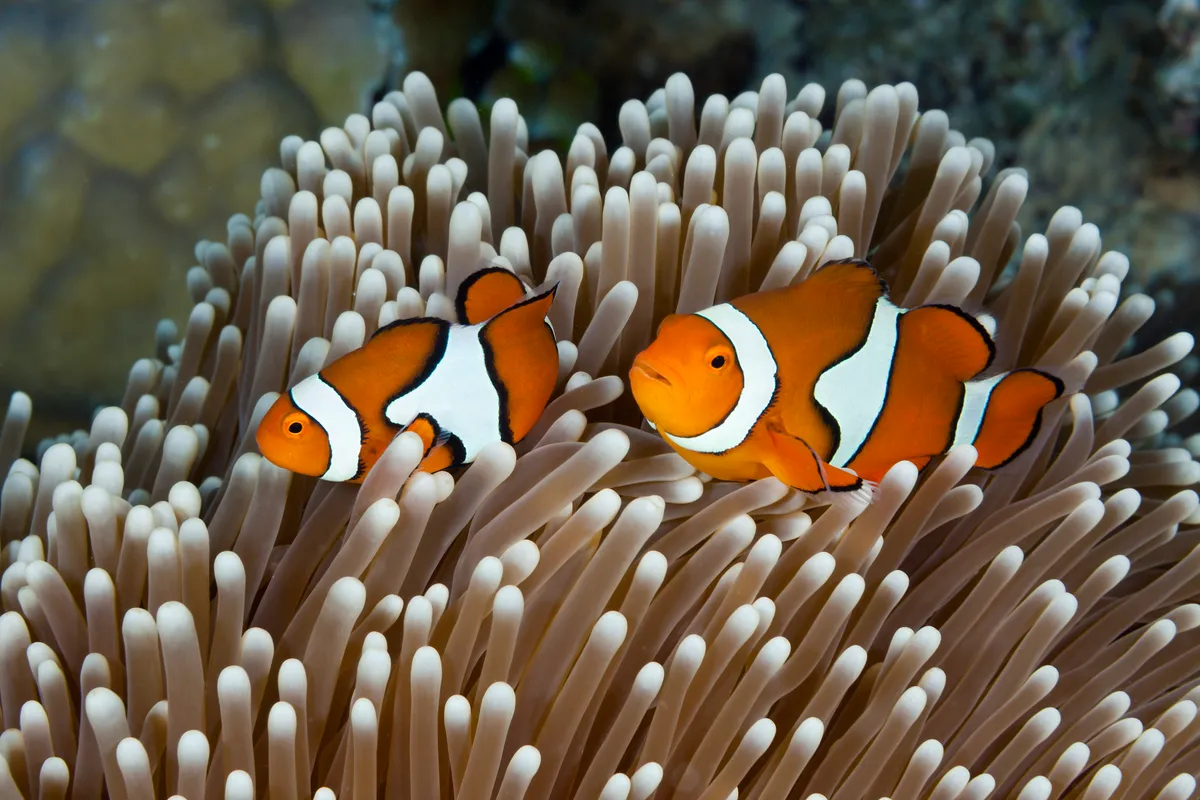

Clownfish (Premnas and Amphiprion genera)

A famous species thanks to the Finding Nemo and Finding Dory films, the orange and white clownfish are distinctive species and have symbiotic relationships with anemones. It’s easy to see how clownfish benefit from living within the protective shroud of an anemone’s stinging tentacles. It gives them a safe home which predators tend to avoid.

Less obvious is whether the anemones benefit from the arrangement or simply put up with their occupants. Studies are beginning to show that in fact the anemones gain in various ways from the partnership. During the day, clownfish chase off other fish, such as butterflyfish, that try to nip the anemone’s tentacles.

And when night falls, clownfish fidget among the tentacles, stirring up seawater and ensuring the anemone has a good oxygen supply.

Also, a clownfish’s urine provides nutrients which stimulate the microscopic algae which live inside the anemone’s tentacles and produce additional oxygen and food, in a similar way to the algae inside corals. Overall, anemones survive better and grow bigger when they have clownfish living with them than without.

This Q&A originally appeared in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Helen Scales.

Yellow longnose butterfly fish (Forcipiger flavissimus)

This aptly-named species is notable for both its bright yellow colouration and remarkably long nose. This extra-long appendage enables the fish to access tiny food items lurking in nooks and crannies in the coral, giving it an advantage over its peers. The species also feeds by using its powerful teeth to rip into bristleworms and sea urchins. Viewed from the front, its snout resembles a pair of forceps, leading to its alternate name of forceps fish.

This Q&A originally appeared in BBC Wildlife, and was answered by Sarah McPherson.

Cleaner wrasse (Labroides spp.)

Cleaner wrasse are a well-known group of cleaner fish that live in symbiosis with larger fish. They provide a cleaning benefit to the larger fish, whilst obtaining food, such as parasites or dead tissue, which they consume. Occasionally they have been known to ‘cheat’ and to consume healthy tissue and mucus, and they can prioritise cleaning ‘high-status’ clients such a sharks or groupers over smaller species.