1. What's in a name?

The Galápagos Islands were actually named after the Galápagos giant tortoise as ‘galapago’ is a very old Spanish word for ‘tortoise’.

It is thought that the tortoise ancestor, possibly a pregnant female, floated over to the Islands from mainland South America 2-3 million years ago. At least 14 species of Galápagos giant tortoise evolved in that time, but of these only ten still survive.

2. Adaptations

Like all species in the Galápagos Islands, each of the different tortoise species has had to adapt to a unique environment, and therefore the species vary in size and shape. However, all of them can be classed in two main shell types, domed and saddle-backed.

Dome-shelled tortoises tend to live on large, humid islands where there is plenty of vegetation to eat, so they don’t have to stretch to reach it.

Saddle-backed tortoise have an upward curve in the front of their shell, which allows them to stretch up to reach higher growing plants as they tend to live on arid islands where food is harder to find.

3. Engineering tortoises

Galápagos giant tortoises have become key ‘ecosystem engineers’ in Galápagos, shaping their islands. By carving paths through the scrubby vegetation, they open up key areas for native plants and animals.

In addition, they eat an astonishing amount of vegetation and are important seed dispersers. Research has shown that a single pile of tortoise dung contained over 6000 seeds from nine different plant species!

4. Tasty tortoise meat

Historically the Galápagos giant tortoise populations were decimated by whalers and pirates. It is estimated that over 100,000 adult tortoises were hunted for food. Due to their large size and ability to survive long periods of time without food or water, they were loaded on to boats for food.

Galápagos giant tortoise © Vanessa Horwell

5. Disruptive arrivals

With the arrival of humans to Galápagos came the arrival of invasive species, which have also detrimentally affected the Galápagos giant tortoise populations.

Rats, pigs and fire ants all predate on tortoise eggs, feral dogs attack adult tortoises, cattle and horses trample nests, and goats compete with tortoises for food. Of the ten surviving species of tortoise, two are listed as critically endangered and two as endangered.

6. Answering key questions

Despite their iconic status, surprisingly little was known about Galápagos giant tortoises until a few years ago – their abundance, distribution, movements and diet were all understudied.

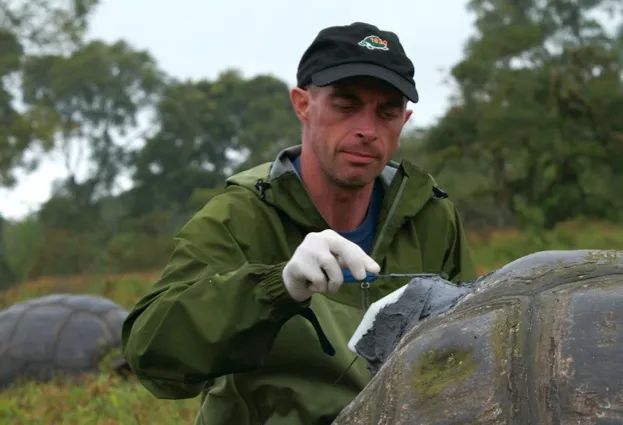

Dr Steve Blake tagging an adult tortoise © GTMEP

The Galápagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Programme (GTMEP), run by Dr Steve Blake and supported by the Galápagos Conservation Trust, was set up to answer some of these questions with the aim to identify where conservation measures are needed. By tagging individual tortoises, the project has gained insight into the migration routes of adult tortoises, and their importance to the landscape.

7. Trying to track babies

Even less was known about the lives of baby tortoises, despite the fact that the years when tortoises are most vulnerable are the ‘lost years’ between hatching and sub-adulthood.

Through monitoring nests, and tagging and tracking hatchlings, the project can ensure that suitable conservation measures are put in place. Unsurprisingly, tracking baby tortoises has proved to be more challenging that tracking the adults!

8. Living alongside each other

With an increasing human population in Galápagos, there is increasing development and agriculture on the islands, and this is affecting the giant tortoises by blocking their ancient migration routes.

The project now aims to inform the development and implementation of land-use policies that will allow both humans and tortoises to thrive long into the future.