When you read a headline saying, “Twitchers flock to see rare bird”, what do you understand by the word ‘rare’?

In this context, the bird is not ‘endangered’ (apart from being ‘in danger’ of being trampled by bearded men), it’s just on its own.

Yes, a rare bird is a lost bird, and not surprisingly, this mainly happens to long-distance migrants, the ones that boggle us by the distances they fly and the routes they take across oceans, deserts, mountains, forests and cities. Why do they get lost?

Sometimes it is a malfunction of their internal ‘satnav’, but mainly it is the effect of extreme weather. In spring, a migrant flying north may get literally carried away by the ease and joy of soaring in clear blue skies on a warm southerly breeze and unwittingly overshoot its intended destination.

A warbler that meant to nest in France may end up in Shetland. It won’t find a mate and it won’t find its way back either. In autumn, it is most likely to be strong winds that are the problem.

Powerful airstreams from the east may transport birds from as far away as central Russia or Siberia, but most of our wind comes from the west, sometimes originating in America.

Last month, while I was heading for the Isles of Scilly, Hurricane Irene – or was it Katia? – was racing north-east off the coast of North Carolina. I don’t remember her name, but she was a fast lady.

In little over a day, she swept across the pond, expending so much energy that she was demoted to a tropical storm by the time she reached here.

In Scilly, we only felt Katia’s tail end, but that was frisky enough to make my walking against the wind far more authentic than anything Marcel Marceau ever achieved. I headed for calm in the lee of a hill, suspecting that any sensible birds would do the same. Indeed, I barely felt a breeze as I leant on a five-bar gate and scanned the field in front of me.

Bisecting the short grass was a strip of bare earth, which I later discovered was where a pipe had been buried. The scar was sandy, with a few pebbles and a shallow puddle. Wheatear habitat, I said to myself, but saw none.

“Okay then, wagtails.” Sure enough, a white wagtail trotted out and duly wagged its tail.

“But what’s that?”

A little bundle of pearly edged feathers.

Asleep?

Exhausted, more like!

A buff-breasted sandpiper, just flown in – or blown in – from Arctic Canada, which is where they breed. Most of them migrate south to Argentina down the Great Plains flyway, but a few usually reach Britain and Ireland.

As this fragile little traveller sighted Scilly, it must have sought out somewhere that reminded it of home, a tiny patch of surrogate tundra. Which is where the scratchy path scoured by the local pipelayer and a puddle just like one left by melting snow came in handy.

Okay, not exactly the Yukon, but comfortingly familiar nevertheless.

The next day, it carried on to the airport on St Mary’s, where it found lashings of close-mown grass and another seven buff-breasts! That’s not a vagrant, it’s a flock!

Which makes me wonder, do they really get blown over and then find each other by luck? Or do they mean to come the transatlantic route and pre-arranged a rendezvous? Great Plains? Boring! See you in Scilly.

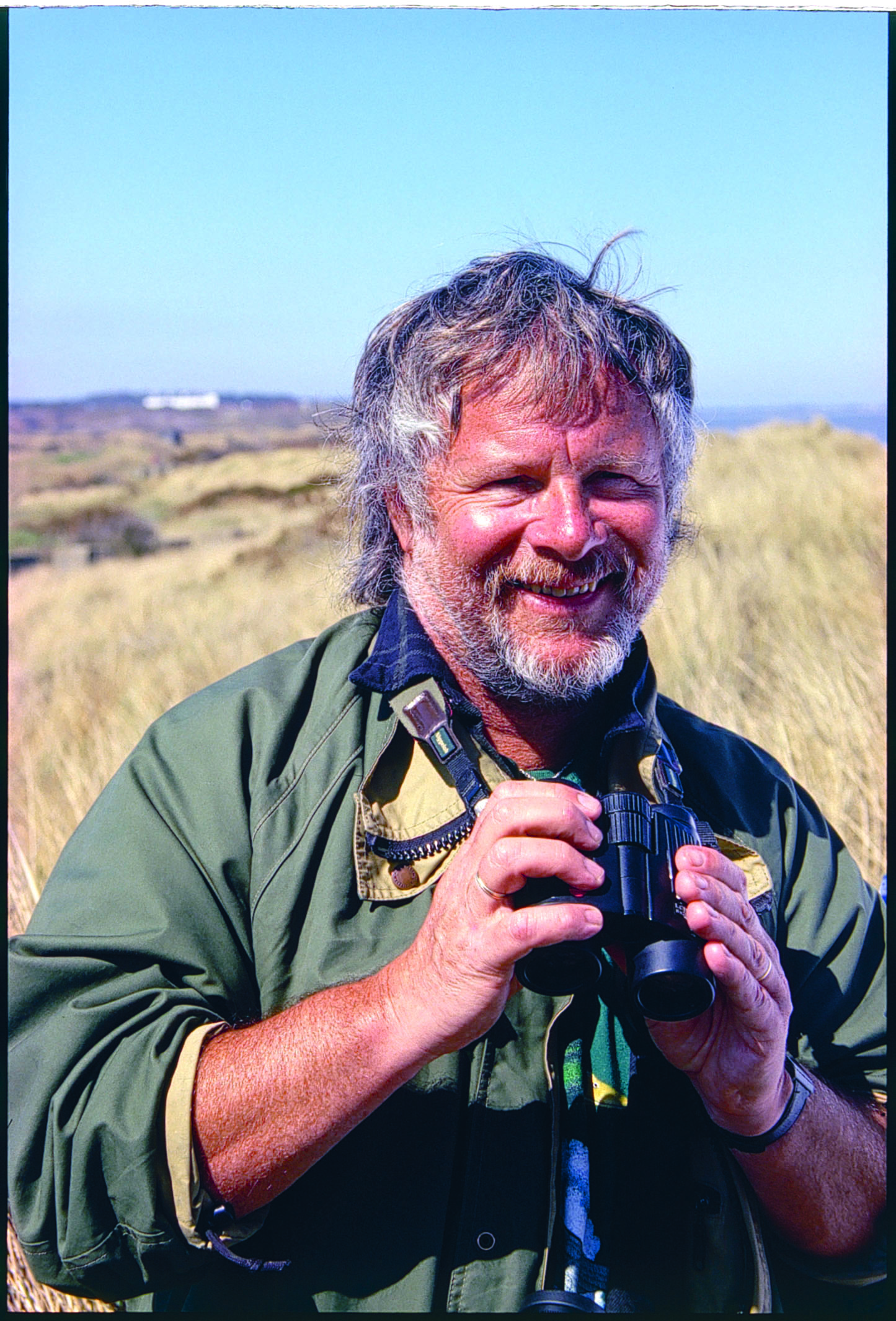

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column may well be a bit of both.