Almost all animals have eyes to sense light in their environment – even in dark habitats such as the deep ocean, where the only source might come from the odd burst of bioluminescence.

But although species across the animal kingdom have evolved various structures for sight, they all need special cells called photoreceptors.

What are photoreceptors?

Photoreceptors are cells that transform light energy into electrical signals that can then be interpreted by the brain. There are two types based on shape: rods and cones.

Rod cells are built for contrast (black versus white) and contain the light-sensitive pigment rhodopsin.

A cone cell will carry one of many pigments, each tuned to a specific range of wavelengths – matching a colour – on the visible spectrum.

The number and type of photoreceptors an animal has dictates which colours it can perceive. A human retina has roughly 120 million rods and six million cones. The cones are split into three kinds or ‘spectral classes’ for trichromatic vision (around red, green and blue wavelengths).

In comparison, butterflies and mantis shrimp have a dozen classes to cover a broader range of the spectrum (from deep ultraviolet to far-red light), which gives them hyperspectral vision.

But there’s more to sight than sensing light, right?

Very poetic! Yes, vision also requires neural circuits. The electrical signal generated by a photoreceptor is relayed via branching neurones that connect to other nerve cells, which amplify or dampen signals before they reach the brain.

The brain then processes complex patterns in that visual information to detect the edges of objects and form an image of the outside world.

Speaking of circuitry, how’s this for ‘intelligent design’? In vertebrates like humans, light only hits photoreceptors after passing through the neural wiring. But in cephalopods, eyes are wired sensibly: behind light-sensitive cells.

Why do animals have pairs of eyes?

Well, one reason they come in pairs is so animals can calculate distance. But like most features, sight is an adaptation to an ecological niche, leading to a trade-off.

Prey (such as deer) typically have monocular vision – an eye on each side of their head so two fields of view can be combined into one large visual field, helping them watch out for hunters.

But predators (such as lions) have binocular vision, with forward-facing eyes so fields can overlap for depth perception, helping them spot food.

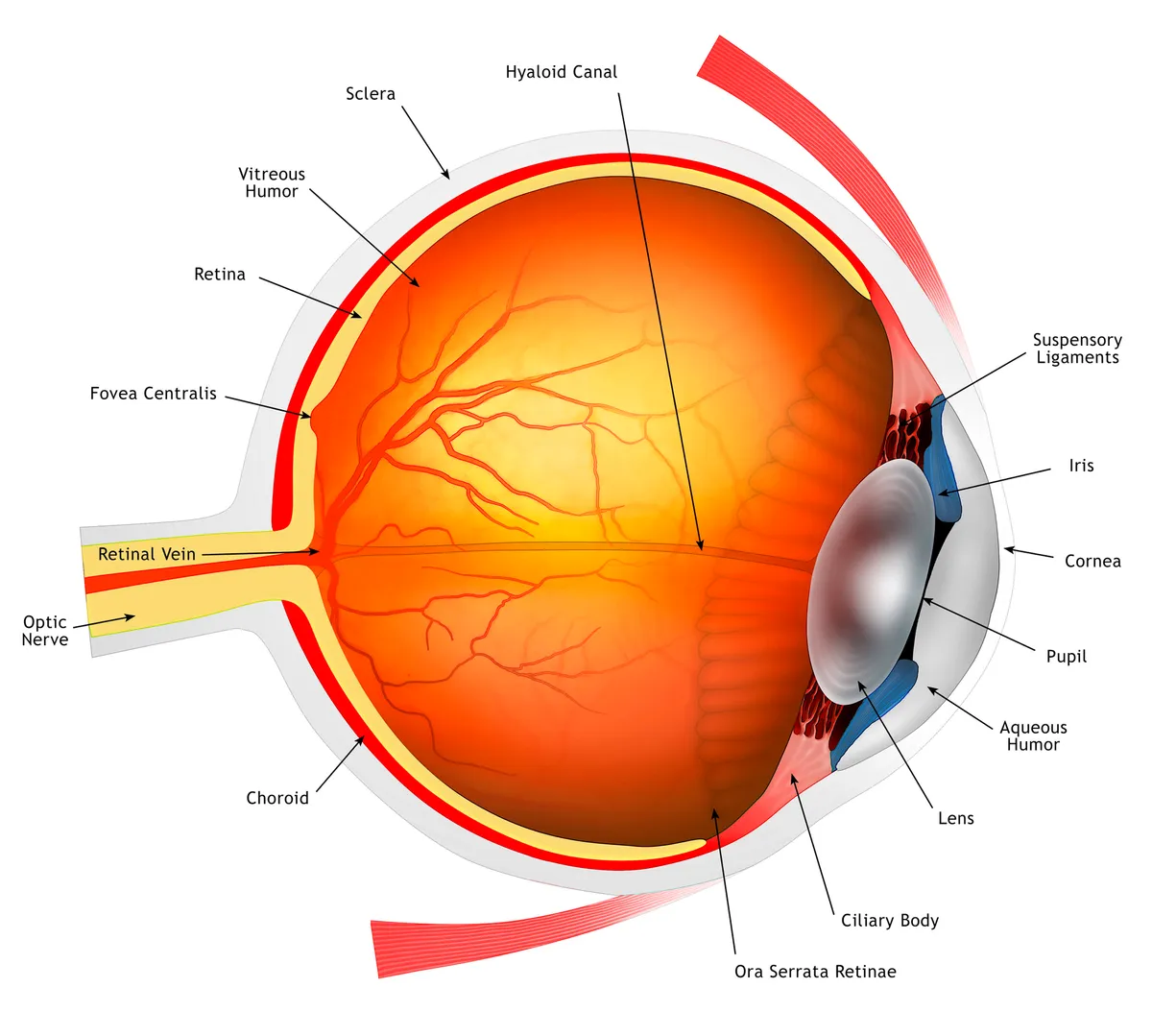

Eyes have a layer of photoreceptors and neurones – the retina – spread across a curved surface so that the brain can compare light and shade on separate cells to deduce direction.

Evolution has since elaborated on that basic plan to create a variety of eyes – 10 distinct forms, in fact, with two main kinds: simple and compound.

What is a simple eye?

The organ is simple because it’s made up of a single chamber with a concave retina at the back of the eye.

Some worms, larvae and molluscs have open ‘pit eyes’, but more complex creatures have a closed eyeball with a window (cornea) to help direct light beams to numerous photoreceptors on the retina.

Many animals have a diaphragm (iris) that adjusts the amount of light entering the eye through its aperture (pupil).

To produce sharp images, scallops and certain crustaceans use mirrors, but the majority of species focus light using lenses. Fish and other aquatic organisms have a spherical lens, whereas land animals have a disc lens and the eye is filled with a gel or ‘vitreous fluid’ that refracts light as it travels from air into the fluid medium (like a ‘bent’ straw in a glass of water).

What is a compound eye?

It’s composed of multiple chambers, optical units called ommatidia, arranged in a convex structure. While each ommatidium only captures a blurry image, because it directs light at narrow angles to relatively few photoreceptors, the signals from each facet are pieced-together by the brain to from one pixelated image.

The multifaceted eyes of insects aren’t inferior, merely different. If a simple eye is like an HD television, a compound eye resembles the wall of screens in a CCTV control room: each individual screen doesn’t show much detail, but a change to one is noticeable and reveals sudden motion.

This helps explain why a house fly can easily avoid being swatted by, say, a rolled-up copy of BBC Wildlife.

More by JV Chamary

- Torpor: what it is, why it’s important and how torpor differs to hibernation and sleep

- Endosymbiosis guide: what it is and why complex life needs endosymbiosis

- Torpor: what it is, why it’s important and how torpor differs to hibernation and sleep

- Photosynthesis: what it is, how it works and why it fuels life on earth

Do all primates have colour vision?

Among mammals, only primates and marsupials have colour vision (trichromatism). Within the primates, however, the adaptation varies.

South American night monkeys, for instance, can no longer see in colour, while Old World monkeys and apes can detect the full range. New World monkeys and some lemurs are even ‘polymorphic trichromats’, meaning the ability to see in full colour is split within the species: some females can see red, green and blue (the primary colours for light), but the vision of others and males (the ‘dichromats’) peaks at green and blue.

Studies have shown that trichromats are better at spotting red and orange fruits, but dichromats are thought to have the advantage when light is low or fruits are camouflaged. With many South American primates foraging co-operatively, this split in visual ability seems to improve feeding success.

Ben Garrod

Can any animals see colour in the dark?

As a rule, vertebrates can either see in colour, or they can see in low light levels – but cannot do both at the same time. The retina is lined with two types of light-detecting cells: colour-sensitive‘cones’,which need a lot of light to function, and ‘rods’, which can handle low light levels but detect only black and white.

Even owls – large-eyed, nocturnal, visual predators – hunt in monochrome. The only exceptions seem to be frogs and toads. Their eyes have a third type of cell that combines the sensitivity of rods with the colour capabilities of cones, enabling colour vision in light levels so low that humans would barely see anything at all.

Stuart Blackman

Do optical illusions work on animals?

Animals and humans can be bamboozled by similar illusions. For example, hummingbirds cannot maintain a stationary hover at a flower presented against a rolling striped pattern, which gives the birds a false impression of movement. There is evidence that zebras’ stripes have a similar effect on predators, causing them to mistime their final lunge for the target, while male great bowerbirds deploy an optical illusion to impress females.

They decorate their bowers with bones, shells and stones in size order – smallest at the front, largest at the back – to give the impression that they are all the same size. It also makes the bower appear smaller than it actually is, which in turn makes the male look bigger.

Stuart Blackman

Main image: Eye of cuttlefish, in Ambon, Moluccas, Indonesia. © Reinhard Dirscherl/ullstein bild/Getty