Peer into the beguiling depths of a rockpool at low tide on a sunny day and you could be forgiven for thinking that this miniature watery world is a haven of tranquility. But nothing could be further from the truth, because a rockpool is one of our harshest habitats.

Life here has to cope with a wide variation in temperature, oxygen levels and salinity, not to mention the turbulent tides that pound rocks and carry in fresh cargoes of predators.

The pools richest in species tend to be nearest the low-tide mark – in these deeper pools lower down the shore, the richness of life can be breathtaking.

Starfish caress mussel beds with their tube-feet, beadlet and snakelocks anemones snare prey on stinging tentacles, and shore crabs fastidiously pick over bits of carrion. Pull back a curtain of fringing seaweed and shannies and near-transparent prawns will dart away to shelter under overhangs. We've illustrated a dozen species to hunt for on your next rockpooling adventure.

All illustrations by Dan Cole/The Art Agency

Learn more about rockpooling and coastal wildlife:

How to identify rockpool wildlife

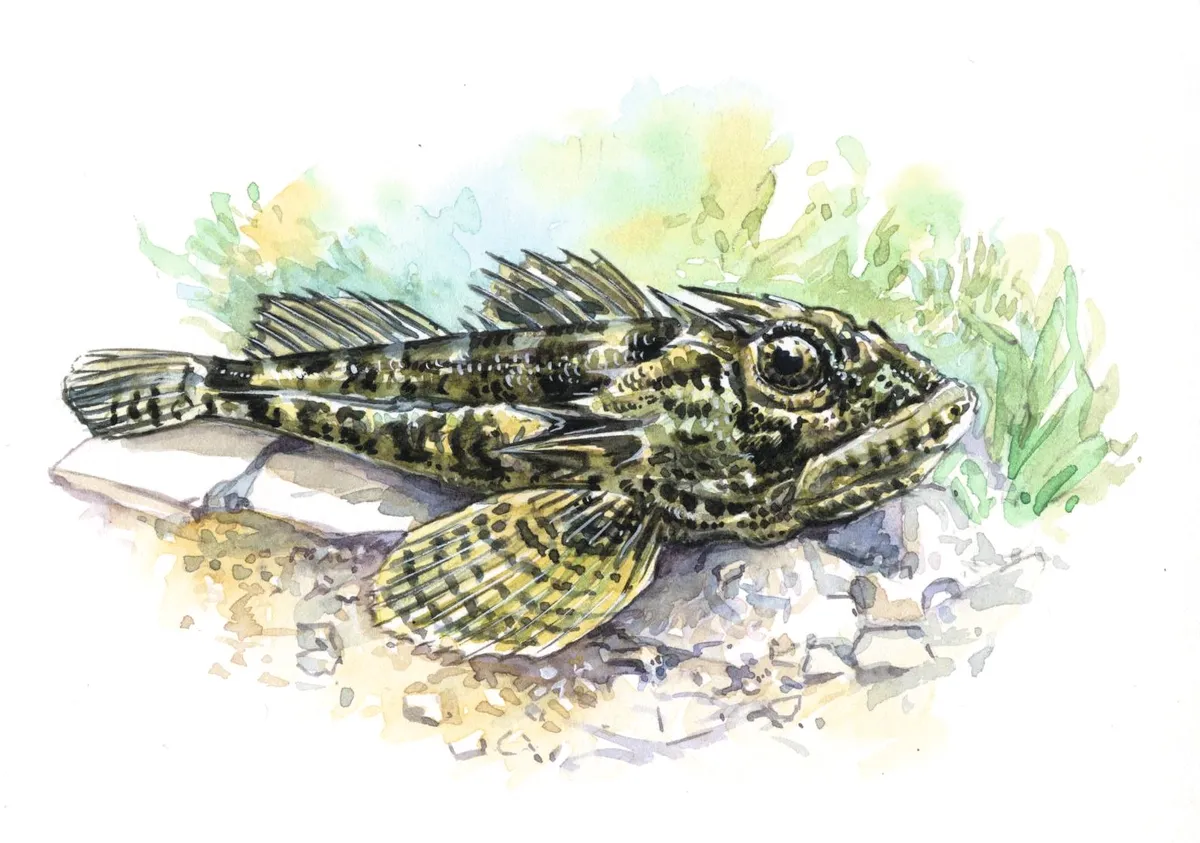

Long-spined sea scorpion (Taurulus bubalis)

This rockpool dweller can grow up to 18cm long and has an unusually large, toad-like head with golden ‘bug’ eyes. Its skin is scaleless, but the gill covers are spiny and there are white barbels at the corners of the mouth. It is coloured to blend in with its surroundings, turning brilliantly pink when among algae and mottled brown when sheltering in seaweed.

In the early spring, your shoreline searches may be rewarded by spotting small clumps of yellowish sea-scorpion eggs in shallow water.

A ferocious predator, the sea scorpion uses its expandable mouth to swallow prey as big as itself. In the UK, palaemonid prawns are a favourite morsel, but it will also eat small gobies and blennies. In turn, the sea scorpion is eaten by larger fish, sea birds, and otters.

Local: easy to see in some spots.

Shanny (Lipophrys pholis)

Also called the common blenny, these fish have the characteristic blunt head, downturned mouth, and long dorsal fin along the whole of their backs.

Like the sea scorpion, it is able to change the colour of its skin to blend in with its habitat. Shanny can be found hiding in rockpools, out of the water, under wet stones and seaweed, or in crevices. They are most mobile at high tide, when they will be found foraging over the shoreline. If you see one out of water, don’t panic – they are able to breathe air.

Shanny feed on bottom-dwelling invertebrates, such as sea snails, barnacles, algae, and crustaceans.

To reproduce, these blennies spawn in distinct pairs from April to August and lay small eggs on the seabed, which the males guard.

Common and widespread.

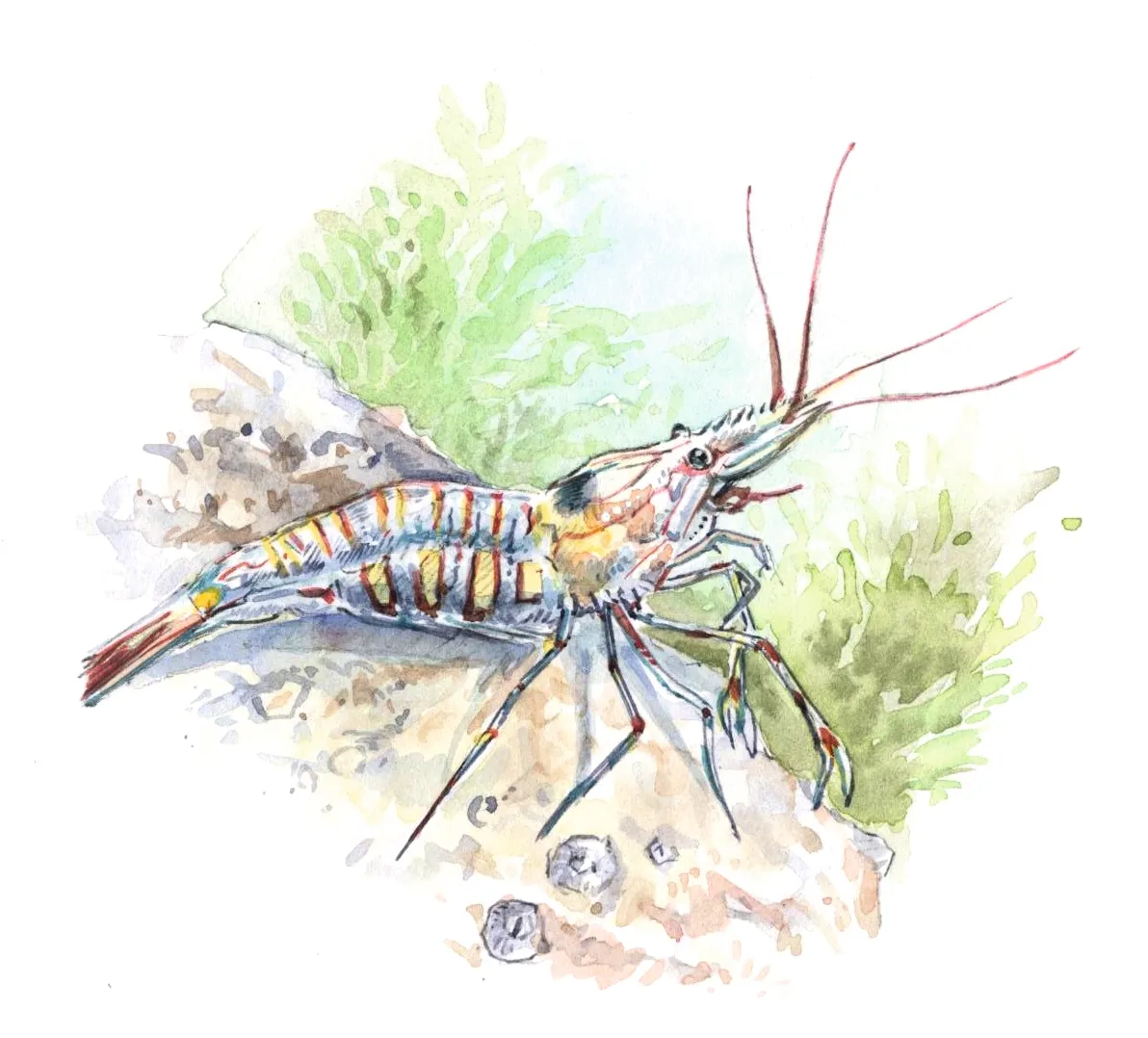

Common prawn (Palaemon serratus)

This prawn can grow up to 11cm and is transparent, with fine, scrawled brown markings. In front of the prawn’s large eyes, dorsal and ventral teeth are visible. The legs and claws have yellow and red banding.

These crustaceans usually forage in groups and when disturbed will dart quickly into crevices or shelter in seaweed. Like most crustaceans, they are bottom-feeders, sweeping up decaying matter such as dead seaweed and mussels.

Eggs are carried on the legs of the female until they hatch.

Common and widespread.

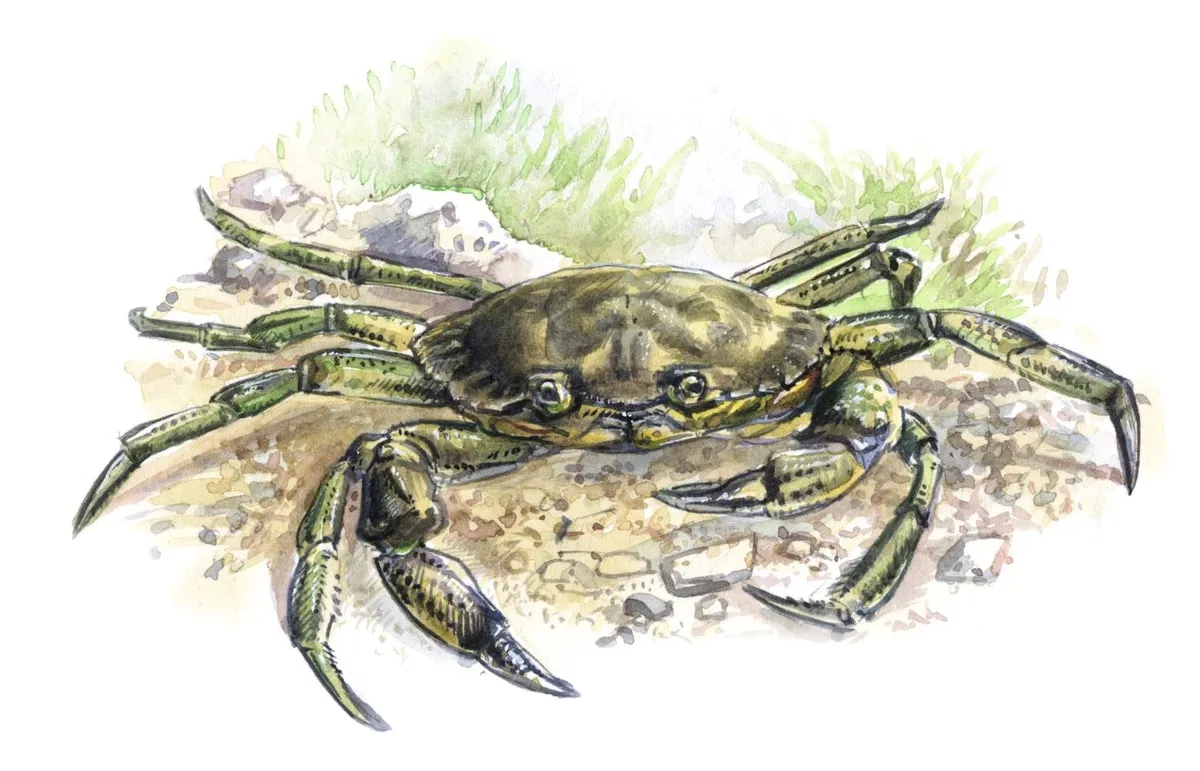

Shore crab (Carcinus maenas)

The shells can be up to 8cm in diameter, with five serrated ‘teeth’ on each side, below the eye. Adults are usually green, but colour can vary throughout the crab’s life, with juveniles generally displaying variation and patterning.

This versatile crab tolerates a range of salinities, making it very adaptable and widespread. While native in the UK, the crab is an invasive introduced species in many other parts of the world, able to establish itself in diverse habitats and decimate local species.

Eggs of the species develop inside the carapace of the female and are dispersed as free-floating larvae in the ocean, where they will undergo many stages before reaching their characteristic crab-like shape and undertaking crab-like behaviours.

Common and widespread.

Common hermit crab (Pagurus bernhardus)

This hermit crab can grow up to 3cm and is red-orange in colour. It inhabits the discarded spiral shells of other species, from winkles to whelks.

Scuffles frequently occur over shells, where one individual may attempt to dislodge another from a favourable shell. The crabs are constantly looking for shells of higher quality, or shells to accommodate new growth. They are also able to remember shells that they have rejected before.

Hermit crabs live in communities led by a dominant male who fiercely competes for resources and mates throughout the year. Most activity takes place during the night-time.

The black eggs take 60 days to develop into adult hermit crabs and are carried by the female until hatching. All hermit crabs are female upon reaching adulthood, but some crabs will eventually develop male characteristics.

Common widespread.

Common starfish (Asterias rubens)

These starfish can have a leg-span of up to 30cm, but rockpool specimens are usually smaller. They have five orange-coloured limbs, with paler stipples. The starfish are widespread over British coasts, but can also live in deep water, where they are paler in colour.

Starfish move very slowly using the hundreds of tube-feet located below their bodies. Their mouth is also located on their underside and is connected almost directly to the stomach. Incredibly, starfish can engulf prey by ejecting their stomach outside of the mouth. It commonly eats molluscs and other bottom-dwelling invertebrates.

They have the power to regenerate if predators take a few arms. They can also reproduce by breaking into two equal halves, or produce offspring sexually by male and female individuals releasing eggs and sperm into the water column.

Common and widespread.

Beadlet anemone (Actinia equina)

The tentacles of this red, brown or green anemone grow up to 7cm. They can tolerate periods out of the water so can be found attached to hard substrate quite high up at low tides. When exposed, or when disturbed, the tentacles retract, making it look like a shiny red pore.

The anemones are aggressive to other organisms that come too close – when another anemone’s tentacles touch it, it stings the intruder. Over the course of several days, attacks persist until the other anemone retreats.

It can eat food found both in the ocean and on the shore, and is an indiscriminate feeder, taking mussels, crustaceans, sea snails, and insects.

Local: easy to see in some spots.

Snakelocks anemone (Anemone viridis)

The pink-tipped, green tentacles can grow up to 18cm and very rarely retract. The anemones are found lower down in rockpools that never dry out, as they must stay underwater at all times.

However, the anemones want to be as close to the surface as they can without drying out because they have a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae, similar to corals, which need sunlight to flourish. The algae live in the anemone’s tissues and give it its colour, as well as providing the anemone with excess food produced from photosynthesis, while the anemone provides them with nitrogen.

The anemones also catch their own food, including large sea snails. They are able to dislodge themselves from their substrate to search for better feeding grounds if needed.

Other organisms also enjoy a relationship with the anemone, including the majid spider crab and Bucchich’s goby, which are immune to the anemone’s sting and are provided with a safe refuge from other animals when settled within its tentacles.

Local: easy to see in some spots.

Common limpet (Patella vulgata)

A very familiar mollusc on our shorelines, where crowds of these organisms attach very firmly to rocks. The greyish-white ridged shells are up to 6cm in diameter and can be spotted most commonly in areas of high wave exposure, probably because they are able to withstand these conditions whilst other competitors cannot. At high tide limpets leave their fixture to graze algae.

Seabirds are a primary predator, but a limpet shell’s conical shape make them difficult to pry from rocks. Below the water, crabs and seawaters prey on limpets.

Reproduction is achieved by free spawning, with males and females releasing gametes into the water, which will fertilise and develop away from the shore.

Common and widespread.

Dog whelk (Nucella lapillus)

Another common seashore sight. The spire of this greyish or yellowish shell can grow up to 4cm high, with a thick rim to the shell mouth.

The dog whelk is carnivorous, boring into mussels and barnacles over the course of days to reach the flesh. They can also attack prey by inserting their proboscis between the plates of barnacles and ingesting the flesh there, which is a quicker method than boring and is usually used by larger whelks.

When feeding, they can be found in aggregations. They prefer areas of high wave action. However, in the winter, the whelks find it more difficult to reattach to the substrate, so usually shelter in rockpools.

The whelks gather to copulate in spring and summer. The eggs are vase-shaped and yellow and can be found attached to hard substrate in sheltered locations.

Common and widespread.

Grey top shell (Gibbula cineraria)

The Latin name literally means ‘ash-coloured hump.’ However, though it is generally greyish, it has fine reddish or purple markings and sometimes red algae can grow on the shell, turning it bright purple or pink. Conical in shape, it can grow up to 1.5cm high.

The snail is found in lower tide pools, where it cruises on rocky substrates or rests on seaweed and algae.

Common and widespread.

Common mussel (Mytilus edulis)

Mussels have a flattened, oval, bluish-black shell, that can be up to 10cm long. The shape of the shell can be affected heavily by environmental factors

Mussels live in tightly clustered colonies on rocks, usually in semi-sheltered spaces such as crevices and on piers. The colonies are fast-growing and attached to each other by threads that the mussels release. Sometimes, older mussels can be covered over by a layer of newer ones, causing buried mussels to die.

Mussels are preyed upon by a variety of animals, including humans. Dog whelks bore into mussels’ shells and eat them, and flounder, starfish and crab are other underwater threats. Land animals, including oystercatchers and ducks, also feed extensively on mussels.

Mussels filter feed and ingest algae and organic material, but can also contain high concentrations of toxins due to this feeding strategy. This fact makes it more risky for humans to harvest mussels because they may contain harmful substances.

Common and widespread.

Main image: Shore crab. © Getty