The morning after a spring gale is an ideal time to walk along the beach to see what has been washed ashore.

Scan the accumulated debris for mammal bones – many of these will be the remains of domestic animals washed out to sea, but among them you should spot seal and whale bones.

- Make a reference collection of the bones you find – it will aid identification later on.

- Most bones will have been cleaned and bleached by the sun, but any that need a wash can be soaked in a commercial denture cleaner or gently boiled in a solution of sodium perborate.

- Never use bleach – it dissolves the bone.

- There are several books that will help you identify your finds, but expect the unexpected. You may well discover the remains of exotic mammals that have died at sea and been thrown overboard, or drifted a long way outside their normal range.

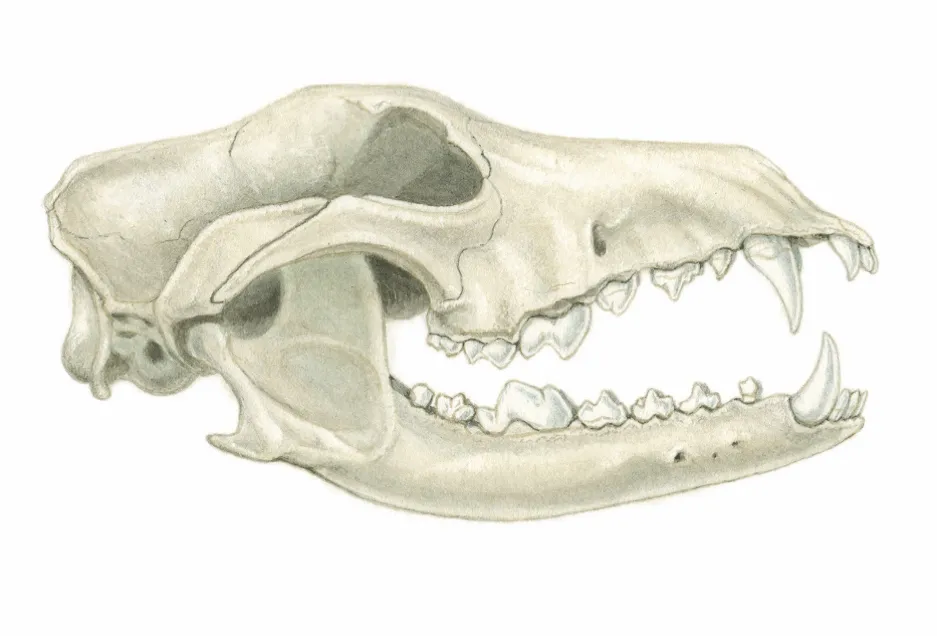

How to identify seal skulls

Seal skulls are superficially dog-like in appearance. There are two species found in the UK - the common seal (also known as the harbour seal, Phoca vitulina) and the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus). Despite their names, the grey seal is actually more common in the UK.

- Common seal skulls are about 23cm long; grey seals 27cm.

- A grey seal skull has a long, wide, high snout that’s associated with its ‘Roman’ nose.

- The cheek teeth of common seals have three distinct cusps. Grey seals have either a single cusp or small additional cusps.

- Limb bones of both species are short and powerful, with bones of lower limbs flattened.

How to identify British seals

Common and grey seals are difficult to tell apart when in the water.

The common seal (pictured) has a relatively smaller head and concave forehead, and its nostrils form a V-shape.

The grey seal has an elongated 'Roman nose' and its nostrils are parallel (they don't meet at the bottom).

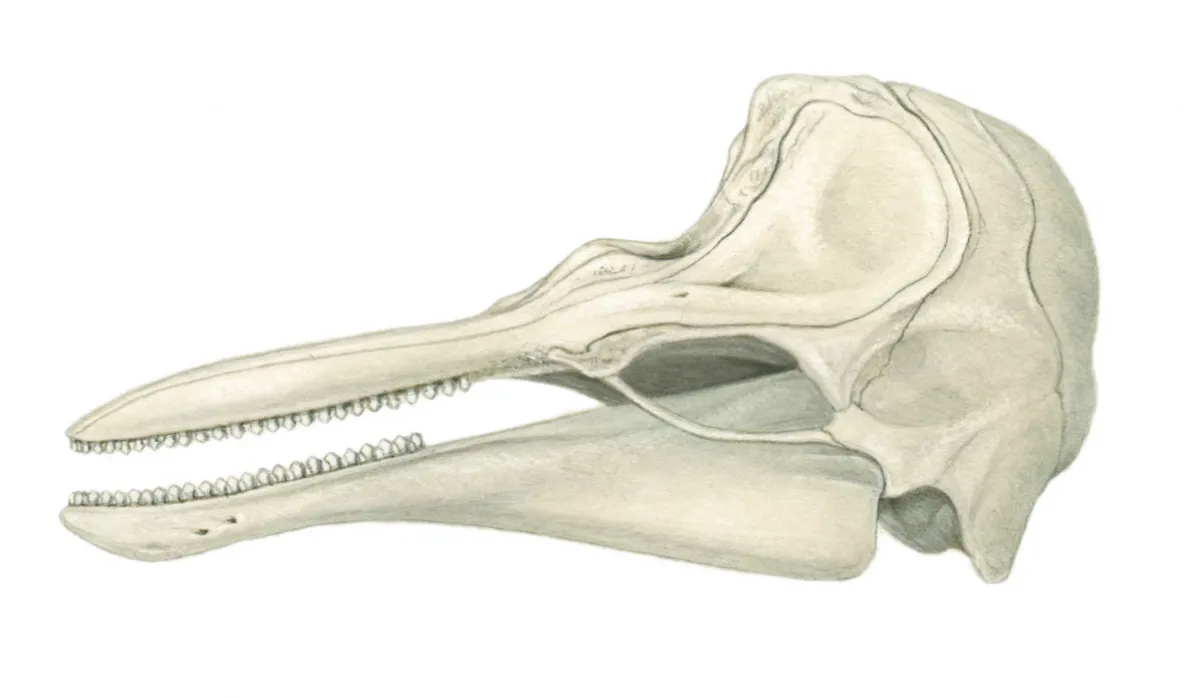

How to identify cetacean (whale and dolphin) skulls and bones

- Toothed whales have a globular cranium, a long or short narrow snout and small, peg- or wedge-shaped teeth. Some species, such as porpoises and bottlenose dolphins, have dozens of teeth; others may have up to several hundred.

- Instead of teeth, baleen whales have a series of several hundred closely packed (generally black) baleen plates on each side of the upper jaw. Baleen plates can be more than a metre long in larger whales. The inner edges are frayed and strands intertwine to form a sieve. The baleen will often be missing by the time a skull washes up on a beach.

- Vertebrae of larger whales can be the size and shape of a kitchen plate.

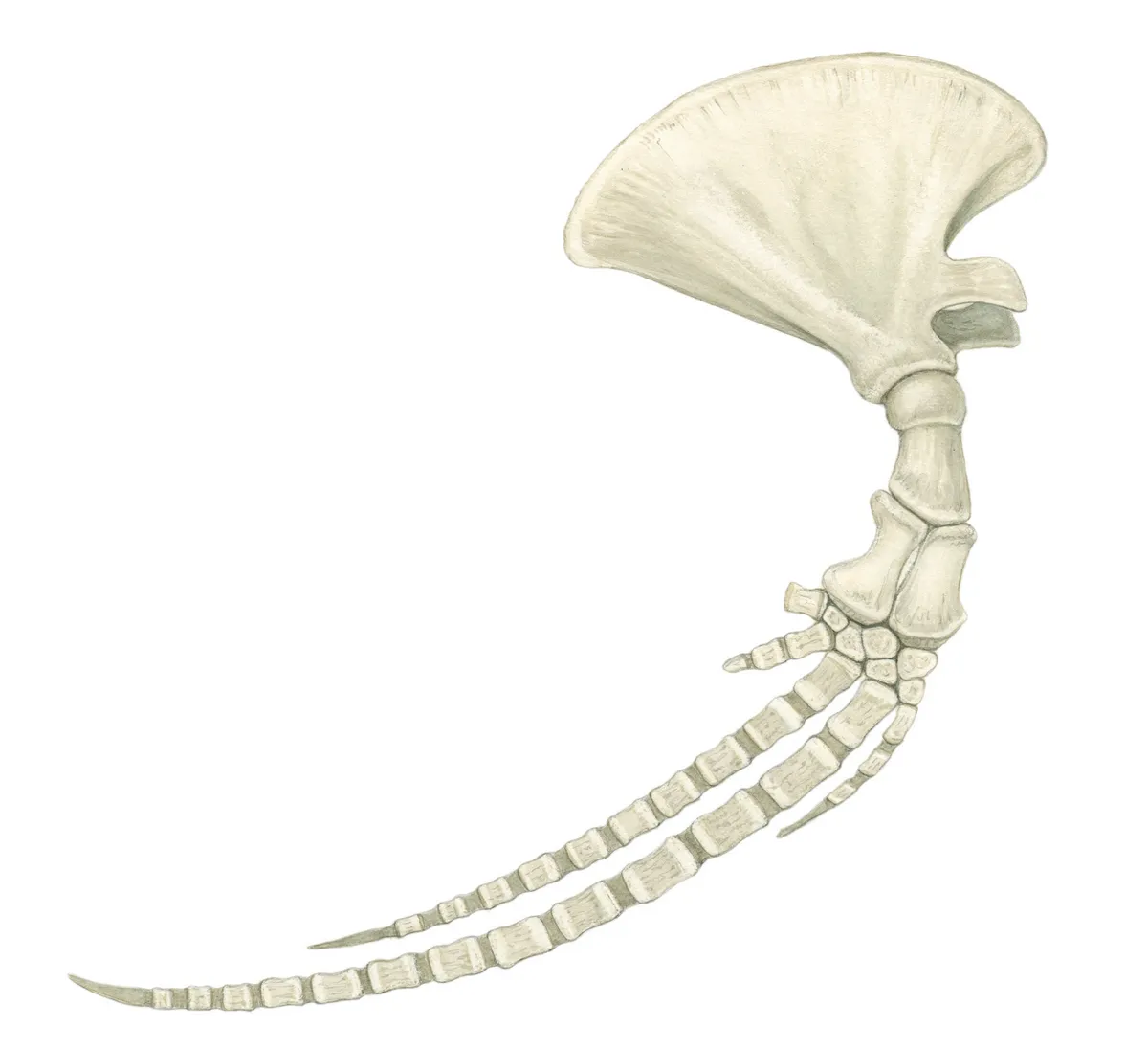

- Forelimbs reduced to a flipper, with phalanges (small bones) flattened and rectangular. Hind limbs are vestigial.

Other bones

- Marine mammals have a range of adaptations that help distinguish them from terrestrial mammals.

- Domestic livestock have a gap between the cheek teeth and front teeth – marine mammals don’t.

- Limb bones of terrestrial mammals are longer and thinner; those of livestock have cloven feet or a single hoof.

- Vertebrae of domestic stock and dogs are relatively smaller with longer bony processes (the bits that stick out) than marine mammals.

What are the differences between a bone and a fossil?

When you see dinosaur skeletons in a museum, you’re not actually looking at their bones but their geologically based replacements. Bones are made from a composite of organic components, such as collagen and fats, and inorganic minerals such as calcium.

After an animal dies, the organic parts of the bone break down over millions of years and leave only the fragile and porous inorganic components, which maintain the shape of the original bones. Water in the sediment surrounding the animal seeps into its bones, carrying with it minerals such as calcium carbonate and iron. These are deposited into the bones’ microscopic pores, making them more and more rocklike while the physical structure remains the same.

Professor Ben Garrod.